| (ARCHIVE) Vol. XIX No. 13, october 16-31, 2009 |

|

Quick Links

Nostalgia: Mylapore, Triplicane

The story of two obelisks

Pages from History: Is he remembered at Presidency?

A light unto the 1920s: Our Print Heritage

Naturalists’ notes: Urban fauna

|

Mylapore

After reading some of the memories of various people about old Madras, I, an octogenarian, wondered why an important segment of people who were there in Mylapore has been left out. I refer to the handloom weavers who were part and parcel of Mylapore, especially of South Mada Street.

At first dawn they used to set up their looms on the road. Then they would go to the Pillaiyar temple, now known as Valleeswarar in South Mada Street (also known as Kaikolar Pillaiyar or Kakkala Pillaiar), and light karpooram (camphor) before starting their work. In fact, T.S.V. Koil Street was known as Kakkala Pillaiar Street. They wove only 4 cubits veshti-s, rather rough in texture, and small red towels known as Kasi Thundu. Weavers’ families would work till about 9 a.m. When the first carts and cycles came along they would roll up their looms and go home.

The first voice you heard in the morning was Amma Pal. It was the milkman with his cow and calf who would milk in front of the lady of the house and measure the quantity required. The next sound was Arakeera, Mulakeera, Sirukeera brought by the Keeraikari. The absolutely fresh greens were so tender and juicy that keerai was a delight to both young and old, specially prepared in a separate kalchatti. Soon after, you heard a weird cry, ‘Ooyee’, translated as ‘Thayir’. It was brought by Kanndigas who wore an extremely dirty rag or kambli on their heads and were balancing a basketful of curd pots. Though the kambli, the basket and the vendors were dirty, the pots contained ambrosial curd. It was laded out with a coconut shell scoop and some extra was demanded by children as kosuru. By now, the streets would begin to get crowded with paper boys, vegetable vendors and others. The menfolk would go for a bath in the temple tank which was unfenced and open to all. Barbers used to ply their trade on the eastern bank of the tank. A number of purohits would be sitting waiting for customers. At 9 a.m. there would be traffic on the road, by now clear of the weavers.

All of them were evacuated during World War II when Madras was evacuated and relocated on the outskirts of Kancheepuram. The last loom I saw was in a house in V.C. Garden Street. Now the weavers have all gone.

Another memory is that of a queue of people in the corner of South Mada Street where the famous Ayurvedic doctor Pilla Pappaiya Patrudu used to practise. The other notables were Dr. Nanjunda Rao in West Mada Street, Dr. Sambasivam in T.S.V. Koil Street, and Dr. T.N. Krishnaswamy in Kutcheri Road. After the men had gone to work, the children went to school (Lady Sivasamy School or Dadi Vadiyar School, now Karpagambal School).

I still remember the lovely smell of the flowers, even before we crossed Sannadhi Street. It was a lovely sight to see the women and girls going to the temple and the mounds of fragrant flowers for sale.

The well-to-do wore silk sarees throughout the day and night and washed them themselves. The sarees lasted many years. The place to buy silk sarees was, of course, Sampoorna Sastriar’s in North Mada Street. A Sastry saree was the equal to Chanel dresses for Mylapore Maamis.

Nine yards and six yards sarees were sold. Customers would go up the steps and sit on the mats in the showroom and a cascade of sarees would be shown to dazzle you. Jewellers, like Sastri and Sastri, also conferred a status symbol on you.

I also remember a few colourful vegetable vendors who used to set up shop in the evening. My first memory is that of Vazhai IIai Sayabu who had a banana leaves shop on a pial in Valleeswarar Koil. You could buy one leaf or order for a large function and he would oblige you with the same smile. The deft way he wielded his knife to cut the leaves was a marvel.

The other side of the temple pial was taken by a vend who sold ‘English vegetables’ like cabbage, carrot, beetroot, etc. and, on rare occasions, cauliflower!

People who wanted small savings facilities would go to the Mylapore Permanent Fund, popularly known as Fund Office. North Mada Street, in contrast to the other Mada Streets, was a ‘U’ area with all the notable lawyers’ houses. Some spilt over into Pela Thope behind.

There were no buses, and pedestrians could walk safely except during festival time when it was a mass of humanity. The best transport was to go to Luz and board the tram which could take you to the Harbour and Town. But as most of the housewives’ necessities were sold by hawkers, the lady of the house had everything at her doorstep and there was no necessity to go shopping.

A forgotten leisurely way of life and a forgotten era, except remembered by old people like me.

Sundari Mani

2A, Nalanda Apartments

2, 5th Street

Dr. Radhakrishnan Salai

Mylapore, Chennai 600 004

Triplicane

We came to live in Thiruvallikeni (better known as Triplicane) sometime after World War II. The Triplicane beach, a favourite place in the evening, had the largest crowd on that vast expanse of sand called the Marina. There used to be a signboard warning of sharks. It had two well-maintained toilet facilities. The cement pathway led to a circular, raised platform where people sat. The AIR broadcast would be aired every evening through loudspeakers.The mobile post office would be at the entrance of Presidency College from 6.30 p.m. Modern Cafe’s mobile canteen would also be at the beach. Its staff would unfold chairs and arrange them before business began. The Aquarium was free and had a good collection. Buhari’s restaurant, adjacent to the Marina swimming pool, had terrace service.

It was during C. Subramaniam’s tenure as a Minister that much work was done on the Marina: the Triumph of Labour and Gandhi statues were installed; two fountains were erected; an inner road was laid; and the beach was lit up at some places with high mast lamps. The fountain near Senate House was short-lived as a doctor’s car crashed into it and it had to be dismantled. The other fountain survived till the late 1970s.

Senate House was where we wrote our P.G. exams and had German classes. Matriculation books for English and languages used to be sold through an outlet in Senate House. The Marina Grounds, where league cricket matches were played, was where we watched C.D. Gopinath, R.B. Alagannan, V.V. Kumar and others play during week-ends. I once watched in awe my friend climb up and down all the arches of the ‘Iron Bridge’ from the south side and return the same way from the north side. Wenlock Park, next to the Marina Grounds, was headquarters for the Scouts. There were three scout troups then. We used to have annual day celebrations and competitions like tent pitching, etc.

Big Street used to be known as Veera Raghava Mudali Street. The Parthasarathy Swami Sabha had its monthly concert programmes in the M.A. Singarachari Hall on the top floor. Before moving to Sankara Gurukulam in Abhiramapuram, Thethiyur Subramania Sastrigal, who lived in Sydoji Street, had the Sankara Jayanti performed there every year. That great institution, the TUCS, started by a dozen pioneers, was there. Every year they had an annual day and issued dividends on the purchases made.

Triplicane High Road was familiarly known as Tram Road as trams used to ply along it. Pycroft’s Road (now Bharati Salai) was full of general stores selling clothes. They were a rendezvous for purohits in the evening; they used to spin yarn with the thakli for poonool. On the parapet wall of Buckingham Canal you could see fishermen spinning yarn for their nets. At the Ghosha Hospital, the gatekeeper would ring a bell almost every other minute, it would seem, announcing the arrival of a new maternity case.

Murali Cafe defied Periyar’s campaign to delete the word ‘Brahmin’ from its nameboard. For years, two D.K. volunteers would arrive at the hotel entrance around 6 p.m., but, before they shouted slogans, they would be whisked away in the waiting police van. It was all very peaceful and there was no violence.

Living near the places called Patel Chowk and Dr. Natesan Square, we were forced to listen to political speeches by the leaders of various parties. We also used to watch the Muharram festival – known colloquially as Maaradi – from the balcony of our aunt’s house in C.N.K. Road. It used to start from the Big Mosque on Triplicane High Road and wend its way to the Akbar Sahib Street mosque. The Hindi Prachar Sabha branch was in Akbar Sahib Street and the Theosophical Society was in Easwara Doss Street. The R.S.S. functioned in Nagoji Rao Street. Sivaji Vyayam Mandal in Bell’s Road served as a gym. Saraswathi Gana Nilayam, popularly known as Lalitha School, still functions from Thope Street.

On Wallajah Road was the Assembly building during Rajaji’s period; it later became Children’s Theatre and then Kalaivanar Arangam.

Life then was unhurried and peaceful. They were glorious days.

Dr. R.K. Natarajan

10, Rajeswari Apartments,

Kalyanapuram Street

Choolaimedu,

Chennai 600 094

Back to top

|

|

|

The story of two obelisks |

| (By Ramanathan Muthiah) |

|

Pullalur (Pollilur, Pollilore) is a few miles away from Pallur, which is on Highway 58, between Kanchipuram and ‘Arokkanam’. Two obelisks, erected in memory of two English officers who served in the East India Company’s army and who were killed in the Battle of Pullalur in 1781, stand in the middle of a paddy field. The road from Pallur is rough and bus connections to Pullalur are few. Two old temples, two government schools, a government-run children healthcare and development centre, and an agricultural co-operative society exist in the present Pullalur.

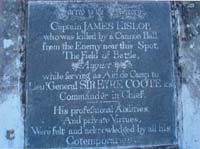

Remembering James Hislop.

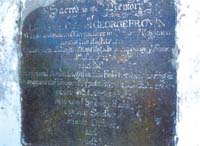

Remembering George Brown. |

Mysore rulers challenged the English East India Company in the second half of the 18th Century. Pullalur was where two battles were fought during the Second Mysore War (1780-1783), one in 1780 and another in 1781. In the 1780 battle, Hyder Ali and Tipu Sultan defeated the English army, which was commanded by Colonel William Baillie and took many English soldiers as prisoners to Seringapatam (Srirangapatana). Hyder and Tipu celebrated their triumph by having a scene from the battle of 1780, popularly known as Baillie-Lally Yudh, painted in their summer palace at Seringapatnam.

Almost a year later, at the same location, the Mysore army led by Hyder and Tipu fought the English – this time led by Sir Eyre Coote. Sir Eyre, who doomed French supremacy in the Carnatic two decades earlier, commanded the English troops in various battles

across the Carnatic. The two obelisks are in memory of two officers who served in Sir Eyre’s army.

A few steps lead to the obelisks constructed on higher ground than the surrounding paddy fields. The text on the front and the sides of the two obelisks is hardly readable.

The obelisk dedicated to Lieutenant Colonel George Brown bears the following text:

Sacred to the Memory of Lieutenant Colonel George Brown

When Lieutenant of Grenadiers in ??? Regiment

he lost his Right Arm

On the storm of Conjevearam Pagoda occupied by Ye French

on the 18th of Apri ????

and fell

in a general Action fought on this Field between the English

Forces and the Troops of Hyder Ally??? Bahaduer

on the 27th of August 1781

esteemed by every Rank

a gallant Soldier,

an able Officer,

and ???? ??? an Honest

Man ???

The second obelisk, in memory of Captain James Hislop, displays the following text:

Sacred to the memory of Captain James Hislop

who was killed by a Cannon Ball

from the Enemy near this Spot,

The Field of Battle,

27th August 1781

while serving as Aid de Camp to

Lieut. General Sir Eyre Coote kbe

Commander in Chief

------------------

His professional Abilities

and private Virtues,

Were felt and acknowledged by all his

Contemporaries.

The battle lasted for eight hours on August 27, 1781 with a ‘dubious victory’ for Sir Eyre; Captain Hislop was an officer of much promise and Colonel Brown was an officer of merit and experience. It is said that Brigadier-General James Stuart and Colonel George Brown lost one leg each from the same cannon ball, and the latter succumbed to the injury.

The present Pullalur is a revenue-cum-panchayat village under the Wallajahbad administrative block of Kanchipuram District. This village was also the site of battle between the Vatapi forces led by Pulakesin II and the Pallavas. Some readers may recall the name of Pullalur referred to in Kalki’s Sivagamiyin Sabatam (Chapter 26).

Local residents told me when I visited the site a year ago that a few cannon balls retrieved from nearby spots, while they were digging for wells some years ago, have been kept in one of the local government schools.

Pullalur is referred to as “the scene of the most grievous disaster which has yet befallen British arms in India”. During my half-day trip, I came to know that there are visitors every now and then, both from India and abroad, to see these obelisks. Certainly, we could do more to preserve such heritage sites in and around Madras.

Back to top

|

|

Is he remembered

at Presidency?

|

(‘Pages from History’

by Dr. A. Raman,

Charles Sturt University,

Orange,

New South Wales, Australia.) |

|

|

As I was chronicling the journals of 18th and 19th Century Madras, I was pleasantly surprised to read the name Gustav Salomon Oppert (spelt ‘Soloman’ in some English references) as the editor of the Madras Journal of Literature and Science for four years. He was a professor of Sanskrit at Presidency College, Madras. The classical German first name ‘Gustav’ struck me and, being an alumnus of Presidency College, I became curious to know more about Oppert. The details I found on him and his contributions while in Madras form the remainder of this story.

Gustav Oppert (1836-1908) Professor of Sanskrit & Logic in Presidency College, Madras

(1872-1893)

|

Gustav Oppert was born in Hamburg, Germany, on July 30, 1836. He studied Ancient Philology, Oriental Studies, and History at the Universities of Bonn, Leipzig and Berlin, respectively. After his doctoral degree from the University of Halle, he went to Oxford University in 1860. He taught at Queen’s College, Belfast, till 1865. He was an Assistant Librarian at the Royal Library of Windsor, where he seems to have strengthened his foundations in Oriental Culture and History, and Indology.

Thereafter, he was for two years at the Punjab University College for unexplained reasons before accepting, in 1872, the professorship of Sanskrit (and Logic) at Presidency College, Madras, succeeding J. Pickford, the first Professor of Sanskrit. For 21 years, Oppert worked at the College. Conjointly he was the Government Translator for Telugu. He returned to Germany after touring northern India, China, Japan, and America, and settled in Berlin in 1894. He worked as a Privat-Dozent in Dravidian languages at the University of Berlin until his death on March 1, 1908.

Oppert’s contributions to Indian history and culture, while he was in Madras, are impressive. He wrote several authoritative books and monographs, starting from the legend and history of Presbyter John (done before he arrived in Madras). A few of the volumes which he wrote while in Madras were: On the classification of languages: a contribution to comparative philology (Madras Journal of Literature and Science, Madras, 1879); On the Weapons, army organization, and political maxims of the ancient Hindoos with special reference to gunpowder and firearms (Publisher? Madras, 1880); and the Original inhabitants of Baratavarsa or India: the Dravidians (Publisher? Westminster, 1893). Oppert edited the Madras Journal of Literature and Science between 1878 and 1882. After leaving Madras, he documented his travels in northern India in an article Reise nach Kulu in Himalaya (Travels in Kulu in the Himalaya) (1895). Oppert’s first Sanskrit work was his Lists of Sanskrit manuscripts in private libraries of Southern India (two volumes, printed by E. Keys at the Government Press, Madras, 1880-1885). He published Die Gottheiten der Indier (Gods of Indians) after he returned to Berlin in 1905. His Contributions to the history of Southern India (Publisher? 1882) was an epigraphical study. Oppert edited the philosophical works Nitiprakasika (1882), Sukranitisara (1882), Sutrapata of the Sabdanusasana of Sakatayana (1893), followed by an edition of Sakatayana’s grammar with the commentary of Abayacandrasuri (1893). While in Madras, he edited and published Yadavaprakasa’s lexicon Vaijayanti and the Telugu poetry of 16th Century Rama Rajiyamu (Narapati Vijayamu) in 1893.

Oppert wrote several professional-journal articles on the anthropology of southern India, too many to list here. Similar to many anthropologists of his day, Oppert endorsed cultural evolution as the dominant explanatory paradigm, after studying southern Indian linguistic prehistory with reference to the Todas and Kotas of the Nilgiris 1. Ramachandra Dikshitar in the Madras Tercentenary Commemoration Volume (1939) refers in positive terms to Oppert’s contributions in organising the Oriental Manuscripts Library and for curating it, while he was at Presidency College.

1 Oppwer GS (1896) Uber die Toda und Kota in den Nilagiri oder den blauen Bergen, Zeitschrift fur Ethnologie 28: 213-221.

Back to top

|

|

A light unto the 1920s

Our Print Heritage |

| (By S. Theodore Baskaran) |

|

|

We left New York early morning and were driving to Maine to spot the Eiders (ducks) and feast on the fabled lobsters. On the way, by the highway, is a popular stop, a barn converted into a store selling antiques. You could get a stylus for your gramophone and other antique parts. The third floor was for books, very neatly organised. I made a beeline for the India section and, within minutes, landed a gem for two dollars, a paperback, Lighted to Lighten 1 by Alice Van Doren published ninety years ago.

The book, addressed to the women of America, is about the women of India, focussing on three pioneering educational institutions, two of which are in Tamil Nadu: Women’s Christian College, Christian Medical College, Vellore, and Isabella Thoburn College, Lucknow. The title of the book is taken from the motto of WCC. Written from the missionary point of view, it is condescending in tone, but documents some valuable information about the three colleges. There are 32 photographs, including two of street scenes in Madras. There is also a portrait of Dr. Kamala Vaithyalingam as a demure, young medical student in Vellore. She later became Head of Cardiology till the 1970s in CMC, Vellore.

We do not learn anything about the author, as there is no note on her. But it is evident that she travelled in India to write the book. There is a graphic description of her motor journey from Vellore to Gudiyatham when she accompanied Dr. Ida Scudder to see her open-air clinic under a banyan tree. Admiring the Eastern Ghats near Gudiyatham she records, “They are among the breathing spaces of earth, which no man hath tamed or can tame.” She talks about the early years of Christian Medical College, Vellore, with its lone building and the dissection room in a thatched shed.

Listing the gifts from India to the West, the author points to the domestic fowl (ethologists point out that all domestic fowl descended from the Red Jungle Fowl of India) and to spices. Talking of Indian epics, she says, “Helen of Troy and Dido of Carthage pale into common adventuresses when placed beside the quiet courage and utter self-abnegation of such Indian heroines as Sita and Damayanti.” She also quotes Tagore copiously.

We get a vivid picture of life at WCC through the author’s description, extracts from students’ letters and from a teacher’s journal. The Natural History Club prepared a check list of common birds of Madras and studied the song birds. The Dramatic Society staged Sakuntala and Savithri.

In addition to brief descriptions of them, we read about work among women in Madras by Mrs. Paul Appaswamy and Dr. Vera Singh. Infant mortality in Madras in 1916 was 355 out of 1000 and these women worked hard to tackle this problem. Gandhiji makes his appearance in the book, when one of its characters described as Dr. Dora Maya Das, discusses the non-cooperation movement and takes objection to the racist overtones it produces. We are not told what Gandhiji had to say.

Books such as this one can be an invaluable source of information for researchers from many disciplines.

1 Lighted to Lighten: The Hope of India. A Study of Conditions Among

Women in India by Alice B.Van Doren, 1922. Published by the

Central Committee on the United Study of Foreign Missions, US.

This book and many such titles, on subjects related to Chennai,

are preserved in the Roja Muthiah Research Library. I learn from

a Google search that this book has been republished. What I

picked up was, of course, a first edition.

Back to top

|

|

Naturalists' NotesUrban fauna |

|

|

|

I am in the process of writing a book on the urban fauna of India. A major objective of this book is to educate people about the little-known, and more importantly, wrongly-known creatures of our urban areas. It is basically a tool to help the reader identify wildlife commonly seen in cities of India and is meant to be a visual guide with basic information on the subject which will aid identification.

The book covers more than 400 species of fauna, both vertebrate and invertebrate, and while the textual matter is ready, some 116 or so illustrations are wanting. Can anyone help?

Preston Ahimaz

Computer footprint

The e-mail and the use of the computer have always been seen as eco-friendly activities as opposed to traditional ways of communication. But it is not as light on the environment as is generally presumed. The storage of e-mail and carrying out search queries, not to mention watching You Tube, leave a heavy ‘footprint’.

All the information on the web is stored in huge data processing warehouses. These huge computer warehouses of steel, silicon and concrete are super chilled by massive banks of airconditioners running 24 hours a day. And, of course, the computers themselves consume a lot of electricity to do the heavy work of assembling data which you summon from your desktop computer. (Not to mention the 200 watts of power that your desktop computer consumes!)

It has been estimated that a single query on Google’s services consumes as much as 11 watts and releases about seven grams of CO2. In addition to the energy costs, there may also be a disposal cost. All the computer servers are routinely upgraded at increasingly frequent intervals, giving rise to the spectre of managing electronic waste (e-waste).

Thousands of chemicals are used in the production of computers, including heavy metals, hazardous and toxic chemicals and PVC, giving rise to pollution problems, especially in poorer countries (including India) where the norms for the disposal of e-waste are not followed.

K.V. Sudhakar

A mobile consequence

When you bring your cellphone to your ear, spare a thought for people of Democratic Republic of Congo. Odds are that your mobile will contain a mineral piece from this central African country: coltan.

Coltan is the colloquial name for columbite-tantalite, a metallic ore. Its high melting point and resistance to corrosion, coupled with its unique ability to conduct heat and electricity, make coltan particularly prized. It is essential for the power-storing parts of cell phones, nuclear reactors, play stations, and computer chips.

On the face of it, coltan mining is an egalitarian affair. Just about anyone with a shovel and a strong back can dig it up. But the picture gets muddied by the guerilla factions that control Congo. Farmers have been forced off their land or into mining as war has ravaged their land. Miners threaten the environment of eastern lowland gorillas. Miners are killing elephants and gorillas on wildlife reserves and national parks. While the numbers of wildlife are dwindling, the environment is being degraded. Coltan mining provides great wealth for warring sides, takes away the livelihoods of people who live on the land, and destroys wildlife.

The main area where coltan is mined also contains the Kahuzi Biega National Park, home of the Mountain Gorilla. In Kahuzi Biega National Park, the gorilla population has been cut nearly in half, from 258 to 130, as the ground is cleared to make mining easier. Not only has this reduced the available food for the gorillas, the poverty caused by the displacement of the local populations by the miners has led to gorillas being killed and their meat being sold as “bush meat” to the miners and rebel armies that control the area. (Courtesy: Madras Naturalists’ Society Bulletin)

Chithra

Back to top

|

|

|

|

|