| (ARCHIVE) Vol. XIX No. 15, november 16-30, 2009 |

|

Quick Links

Nostalgia: Pulse of the past

The barometer and thermometer – his constant companions

Surviving Mambalam (Part III)

Naturalists’ notes: Breathtaking birdwatching

Point of View: Lost Sanctity

| Nostalgia: Pulse of the past |

| (From Footloose and Fancy-tree by Prema Srinivasan) |

|

|

For those of us who have spent our childhood in the area called Luz, many a beloved landmark has been erased by the passage of time and now remains only a piece of memory. Thirtyfive years ago, the long, straight road called Luz Church Road, where the shadow of the church erected by the Portuguese tried to reach out to another venerable shadow, that of the Mylapore temple, was the main artery of Mylapore.

Luz Church |

Luz Church, tucked away in a side road, was built in 1516 and there is an interesting story behind it. The Portuguese Franciscan missionaries sailing from Goa seemed to have encountered a severe cyclonic storm for which the Coromandel Coast has always been quite notorious. As the missionaries prayed to the Virgin Mary to save them from the storm, one of them spotted a welcome ray of light. Rejocing, they called the area in which they made a safe landing ‘Luz’, which meant ‘light’ in their native tongue.

Ruminating over this intriguing piece of historical fact, you come alongside Nageshwar Rao Pantalu Park on the road adjoining the Andhra Women’s Hotel, recalling an era, when life was quiet and there was time to stroll, gaze and reflect. Once the park was crossed, the scent of Amrutanjan used to assail our senses, for, tucked away amidst the greenery, was the place where this precious concoction was prepared for the sake of millions of sufferers of migraine or common cold. The board bearing the name can be seen today but no pleasant fragrance greets the passer-by.

Beyond this was the famous spot in which the evening ‘mail’ van used to stop and many a family living in Luz Avenue would rush to drop their letters in the van. I remember my grandfather, despite his sixty-odd years, resolutely walking to catch the evening post, so that his letters would reach their destination early. Speed Post or the ubiquitous courier service had not yet made its appearance.

I also remember the person selling second-hand books in the area, which continue to be a veritable storehouse for college and school students looking for treasures at throwaway prices.

The Srinivasa Sastri Hall and the Ranade Library still continue to thrive, although the building is in sore need of a fresh coat of paint.

On the other side of the road was Kamadhenu theatre, where once there used to be a lot of hustle and bustle when a new movie was screened. Popular epics like Sampoorna Ramayanam drew a large crowd and the theatre was a scene of screaming children, scolding mothers and youngsters in their finery, enjoying the entertainment in a noisy fashion. Its days are now over.

Close by was Fashion Silk House where our family used to make weekly trips to meet the ‘tailor’. Going to the tailor was an outing by itself and one that was likely to be continuous, for either the tailor was absent during our visits or the custom-made garment would not be ready. However, it was with pleasurable anticipation that we would set out to the store and if the tailor, by chance, delivered the goods, we could always saunter across to the restaurant called ‘Himalayas’ which served the most wonderful grape juice you could ever get.

India Stores I think did exist and the other shops were all in their nascent stage, slowly realising that the area had tremendous potential as a shopping mall. PMP Corner Shop was definitely there, where you could get everything – from the proverbial pin to an elephant.

Perhaps, this is exaggerating a bit, but the shop remained a landmark for decades. Past PMP Shop was Flex, which sold genuine leather footwear and you felt comfortable sporting those made-to-order chappals.

Shopping in the area had an additional advantage – you could savour the aroma of the biscuits from the Universal Biscuit Factory in the nearby builidng. If you turned right after PMP, towards the mada veedhis, there was Gupta’s State Hotel. Rava dosai in Gupta’s was a welcome treat after the shopping spree.

Across the road where you turn to go to Royapettah, there was Sundaram Stores, patronised by many a Mylapore family for their essentials.

Beyond Sundaram Stores was the National Leather Works where you could buy suitcases and footwear, sturdy and likely to last a lifetime. Very often, you side-stepped the fancy stores in favour of the National Leather Works to order the kind of shoes you fancied.

It was possible to saunter in those areas, haggling over the price of mangoes or jasmine yardage on the pavements which were fairly uncluttered and where vendors conducted brisk business.

Carts of fruits would be stationed everywhere, as they are now; today they have to only compete with airconditioned outlets where shopping has to be done without the pleasures of bargaining! My mother always believed that we got a better bargain with the cartwallahs rather than the snooty stall owners.

Even shopping for medicines was done in an informal fashion, chatting with the chemist in a leisurely manner, generally getting more information on the availability or the non-availability of a particular drug.

Today, efficient young people are posted to calculate with their machines, to tackle the serpentine queues and send the customer on his way at the earliest. The Mylapore Pharmacy and R.R. Pharmacy are still doing good business, although we miss the orange glow of Chander’s Pharmacy near Vidya Mandir School.

Everywhere, in the name of progress, there is a rampant consumerism apparent and this seems to be steadily increasing.

I realise that it is not possible to put back the clock, but there is more to life than rushing around like a headless chicken, quite forgetting that we are missing out on the more vital aspects of ‘living’.

The practical consumer admonishes such nostalgic reminiscences by the reminder: “Places and events usually seem rosy in retrospect.” Be that as it may, you can always take heart from the fact that Ford Ikons and Opel Astras (Ambassadors and Fiats have become anachronisms) jostle for parking space near the famous Luz Ganesh temple. The area, founded on religious faith, continues to be sustained by the piety of the people which has remained constant over the decades, despite the distracting physical changes.

Back to top

|

|

The barometer and thermometer –

his constant companions |

(‘Pages from History’ by Dr. A. Raman,

Charles Sturt University, Orange,

New South Wales, Australia.) |

|

|

That the drought years 1789–1794 in India were of global consequence was first formally recognised by Alexander Beatson, then Governor of the British colony of St Helena. Beatson suggested that the 1791 drought, of simultaneous occurrence in India, St Helena, and Montserrat, was a part of a ‘connected phenomenon’. The background data and indicators to what was recognised as a ‘connected phenomenon’ by Beatson were picked from the climate records of William Roxburgh, who was serving in the East Godavari District of the Madras Presidency. Roxburgh gathered temperature and atmospheric pressure data from 1770 and, using those datasets, he forecast the droughts that occurred subsequently in 1789.

William Roxburgh. |

William Roxburgh [1751–1815], a medical doctor, is remembered for his contributions to medicine and botany in India. He scrupulously obtained large volumes of data for nearly a decade and a half, while serving in different parts of the Madras Presidency and, thus, was a pioneer in the field of climate research. He started gathering climate data from the time he set foot in Madras; he obtained relevant measurements three times a day, using a Ramsden barometer and Nairne & Blunt thermometer made by scientific instrument makers of repute in the Britain of those times.

Roxburgh’s paper, presented at the meeting of the Royal Society (London), communicated by Sir John Pringle on January 29, 1777, has the following to say:

“The manner in which I keep my meteorological observations is as follows: A thermometer without doors; a barometer and thermometer within doors: the barometer and thermometer within doors are kept close together, for the sake of correcting the barometer if required. I observe them three times a day as per diary. I also set down the direction and strength of the wind and the state of the weather. I distinguish four degrees of strength of the wind; namely, gentle, brisk, stormy, and what we call a tufoon in India, which you will find marked with the numbers 1, 2, 3, and 4, besides no sensible wind, which is marked with a cypher.”

He goes on to say that he was ashamed that his rain gauge (spelt ‘rain-gage’) was ‘indifferent’ and he could not measure the rainfall with certainty. Roxburgh also lists 26 illnesses (e.g. fevers, liver, liver cough, liver flux, epilepsy, fistula). Detailed measurements obtained over many years led Roxburgh to develop an opinion on the widespread famine and patterns of climate change in British India.

Roxburgh was transferred from Fort St George (Madras) to Nagore near Tanjore in 1778, where he continued to record meteorological details, until he was posted as the Superintendent of the Botanic Gardens in Calcutta, succeeding Robert Kyd in 1793.

James Capper (a senior accounts officer of the Madras Army) had also obtained daily meteorological measurements, including those of atmospheric pressure, at Fort St. George in Madras from March 1777 to May 1778. No match occurs between Capper’s and Roxburgh’s data, although an overlap occurs in the time spans of their records. When adapted to monthly values, the Capper records indicate a convincing relationship with the seasonal cycles of pressure in the long-term means of the Madras monthly sea-level pressure data from 1796 to recent times; Roxburgh’s observations appear less amenable to seasonal cycles of pressure data of Madras. Nonetheless, the Circars suffered severe famines in 1780 and 1789–1792; Roxburgh thought that the irrigation methods practised at that time were more efficient in the specific context of climatic and geographical conditions of the Circars than what were practised in the colonial days; he was critical of the East India Company’s water-management strategies which he felt were badly designed and were essentially responsible for the land’s response with famines. Roxburgh’s comments made in 1793 to the Government were transmitted to Robert Kyd (Superintendent of the Calcutta Botanic Garden) by the Madras Nopalry founder and another medical doctor James Anderson [1739–1809] and were relayed by Kyd to Beatson, who found a link among the drought events that occurred in India and elsewhere in the world and proposed the idea of a ‘connected phenomenon’.

Consequent to documenting details and datasets on the seriousness and impact of the climate change in India, Roxburgh launched an extensive tree-planting (teak) programme in the Madras Presidency (and later in the Bengal Presidency) to mitigate unfavourable environmental changes. While at Samulcottah (Samalkot), he supervised the construction of a botanical garden and trialled tree-planting experiments involving coffee, cinnamon, nutmeg, annatto, sappan, breadfruit, and mulberry; he experimented with cultivating sugarcane and different species of pepper. He advised local administrators to plant drought-resistant and water-efficient food-product yielding palms, such as coconut, sago, date, and palmyra, and non-palm species such as banana, jack, and prickly pear along village streets and canal banks to ensure better supplies of edible plant products for the rural people. His recommendation was accepted by the then Government of Madras, which procured saplings and seeds of coconut from Colombo, sago from Travancore, and jack from the Nicobar Islands for planting in the Madras Presidency.

Roxburgh was honoured for promoting plantation-based utilitarian conservation in India by the Royal Society for the Encouragement of Arts in 1805 and 1814. John Hope’s [1725–1796] tutelage when Roxburgh studied in Edinburgh seems to have influenced his scrupulous skill in data collection. Roxburgh’s interest in systematic meteorology may have stemmed from the influence of John Hope as well as his experiences at the Royal Society of Arts which, in the early 1770s, was greatly influenced by the climate theories proposed by Stephen Hales and Duhamel du Monceau.

Back to top

|

|

|

Surviving Mambalam (Part III)

|

|

|

|

At the end of my first year at Art school I went back home to Ranchi for the summer vacation. Paritosh Sen joined me there and we did a number of water-colour sketches around the hilly countryside of scenic Ranchi. For both of us it was nothing short of an aesthetic revelation. The year at Art school, although educative and enjoyable in many ways, was also quite frustrating. I had too many lofty dreams about being an artist but too little experience or skill. I was also too shy, self-conscious and new to discuss my problems either with my friends or with Devi Prosad. As I grew more relaxed with the out-door sketching, I started seeing in nature not only colour and form but also what I was looking for in my personal expression as a painter. This simple but intense experience while painting out of doors with Paritosh did not turn me into a fine painter overnight but gave me courage and a sense of direction in my attitude towards creativity.

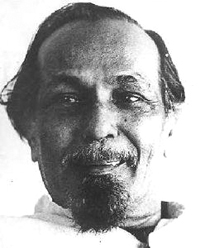

K.C.S. Paniker. |

While in Ranchi, I received a letter from Paniker – “I have found a nice little place in Mambalam, very quite and peaceful. It is also very inexpensive. We three can live there and work seriously. Ask Paritosh and let me know. After hearing from you I will pay the advance to the land-lord.”

It was a new isolated house less than half a mile from Mambalam electric train station. The rent was 14 rupees a month – barely within our small uncertain budget. Mr. Mudaliar, the kindly landlord, who had recently returned to India after many years in Singapore occupied most of the small house with his family. We had two rooms on one side of the house. One of the rooms we used for cooking and for storage of our few belongings. The other, next to a small verandah, was set up for working. Behind the cooking room in the walled in-yard was a well where we bathed and from which we got our drinking water. There was no running water in the house and no electricity either. We used a hurricane lantern for reading. We had no furniture, just three bed rolls. The simple cooking was done on a primus stove borrowed from Paniker’s elder sister in Egmore. The few pots and pans for cooking also belonged to her.

The Indian and World Arts & Crafts is a journal we had never heard of till a well-wisher sent us a fascinating series of articles that appeared in it in 1985. They were by an expatriate artist and art critic SUSHIL MUKHERJEE, who in them looked back at his memorable days at the Madras School of Arts then headed by the renowned artist Devi Prosad Roychowdhury as well as painted a picture of Madras in the late 1930s and early 1940s. The series titled ‘Devi Prosad and His Disciples at the Madras School of Arts’ is featured in these pages in a somewhat abbreviated form. |

Since we went to school early in the morning and spent most of the day there, our lunch was usually at Ramaiya’s – just a cup of tea and, whenever we could afford it, something to eat. On holidays and nights we cooked at home. The cooking was without any frills. When we had the money we bought enough rice in a sack and some ghee to last for a month and our monthly passes for the electric train. We also bought onions and duck’s eggs which were cheaper and bigger. We would clean the eggs with soap and water and then put them into a pot with rice, onions and water to boil on the stove. It was no gourmet meal but we enjoyed it all the same. Our breakfast used to be Bengal gram soaked in water overnight and a cup of tea.

In front of the house was an open field which stretched as far as eyes could see. In the field there were a few cultivated rectangular green, yellow and ochre patches where during the day men and women worked in the blazing hot sun. In the distance, perhaps a couple of miles from our house and hugging the horizon, was a village. Our only neighbour Mr. Chettiar lived in a fairly big house about a furlong from us. Because they had just moved into their new house and their well was in the process of being dug, Mr. Chettiar’s young daughter used to come to our well every evening carrying a brass pot on her hip to fetch water.

* * *

One day late in the evening, as I sat and played my flute in our work room, Paniker who was seated next to me on a bed roll said, “Sushil, will you do me a favour? I need your help very badly. I guess you have seen our neighbour’s daughter coming to the well.” I stopped playing and said, “Sure, she is a beauty, so what?”

“Well, you know, Sushil, she fascinates me. I have made eye contact with her and she has responded. I think she likes me. But I feel I have to do something more before I can go and hold her hands. You see, Sushil, I have noticed that when you play the flute she stops and listens. Now, this is how you can help me. Tomorrow when she comes to the well you could sit near the window of the room next to the well and play your flute. I will take one of your spare flutes, stand at the open window and act like I was playing it. That would impress her and make it easy for me to approach her. What do you say?”

The next day in the evening we sat on the verandah, waiting for the girl to show up. Suddenly Paniker said, “There she is. Come on, Sushil, let’s go in.” I could see her in the distance over the low compound wall. We hurried into the cooking room. Paniker stood before the window with a flute in his hands, cross legged like Krishna, and I crouched behind him below the window. “Play something sad and romantic,” Paniker said. I started an alaap in Triveni. Paniker was moving his body with the music, his fingers going over the holes of the flute like a virtuoso flautist’s. After a while he whispered through the corner of his mouth, like a Chicago mafia, “She is here. Keep it up, lad.” I kept playing for some time, but finally curiosity got the better of me. I wanted to see for myself what was happening. So still playing, I stood up behind Paniker. She was there all right – turning her head once in a while to look at Paniker and coyly smiling with dark eyes downcast. I don’t know what overtook me but, suddenly, I stopped playing. Paniker, not immediately realising that I had stopped playing, kept on moving his fingers over the flute and shaking his head – only there was no sound. He was like a flute player in a silent movie. The girl instantly caught on to our trick and started giggling. For a few seconds Paniker looked at me with such malevolence that I thought he was going to hit me with the flute. Then suddenly all three of us started laughing hysterically. We just could not stop laughing until we felt sick and breathless from laughing.

A few weeks after the incident Mr. Chettiar’s house was all agog with the excitement of a wedding. Mr. Chettiar didn’t know us and so naturally we were not invited. Late in the evening Mrs. Mudaliar, our landlord’s wife, returned from the wedding. She gave us a package wrapped in banana leaf and, with a knowing smile, said, “Shakuntala is getting married to an engineer from Jamshedpur. They are leaving tomorrow. She sent this for the three of you.” We went in and opened the package. There were lots of laddoos and Mysore paaks in it.

* * *

We worked very hard that year. War had broken out in Europe but its impact was still only a distant thunder in India. Paritosh was always talking about doing something new. Paniker was more conservative. He still painted tightly composed, genre paintings of Malabar. His more adventurous works, group compositions in oil indicated definitive influence of and admiration for the styles and techniques of Devi Prosad and the English painter Frank Brangwyn. As for myself, I was beginning to feel more confident as a painter but still trying desperately to reach for the moon with six pence in my pocket.

One day, we discovered that we had run out of provisions, there was only a small packet of tea and some Bengalgram. We had no money either – not a penny – and the date of our train passes had expired; Paniker ruefully observed, “We must be under the influence of Shani.” However, Paritosh, ever optimistic and undaunted, managed to jerk out a whole cup of rice hiding in the old gunny sack. “Now we must search and find some money to get a few other things for lunch,” he said.

We searched every pocket and carefully looked into our suitcases and boxes. It was futile, there was no money. Paniker had a large water-colour paint box, full of watercolour tubes, some of them used up, some dry, and a few brushes. It was just a dirty old watercolour box out of which Paniker always managed to extract enough paint for his sparkling, fresh, Cotmanish landscapes. Paritosh opened the box and started searching for money. “No use searching for money in my box, Paritosh, I know, there’s none. Don’t waste your time.” Paniker told him.

“The hell you say,” Paritosh shouted, “there’s money, see there’s money, seven bloody pies.” They were smeared with paint and had also oxidised. Paritosh carefully wiped the paint off and cleaned them with soap and water until they sparkled and looked like new. “But what can you buy with seven pies?” I asked him. “Aaray baba, this is legal tender, I tell you I can buy something with these pies. Can’t I? Come on, light the stove, start cooking the rice. I’ll be back from the market soon.” He put on his long white kurta and white dhoti and went off with the seven pies. Paniker said, “Well, we can always have green chillies with rice and salt.”

Paritosh returned after an hour. “Come and see what I have brought. We’ll have a damned good meal.” We couldn’t believe our eyes. From his kurta pockets and the front folds of his dhoti, like a magician, he carefully took out four duck’s eggs, two onions, two potatoes, a few okra, green chillies and a handful of spinach. “My God,” I asked, “how in hell did you manage all this?” Paritosh just smiled. “Aaray baba, I went to Rukmani’s little shop, you know the dark woman like a Chola bronze, with large flashing eyes and high pointed breasts. She likes me very much. I sat near her and talked to her (Paritosh spoke fairly good Tamil) and you chaps should have seen her. She was so happy and excited. While talking to her I spread the front of my dhoti over the nearest baskets and helped myself to some of the stuff and quietly put them into my pockets. Well, I did buy the onions, green chillies, okra and the potatoes with the seven pies. She gave me the spinach as a friendly gift.”

“I know why she gave you the spinach as a gift,” Paniker said. “She wants you to be healthy and strong. Simple maternal instinct, I should think.”

“Well, I don’t know about maternal instinct, but I think I will go and see her soon. She is really gorgeous. I wonder if she would pose in the nude for me.”

(To be continued)

Back to top

|

|

Naturalists' Notes Breathtaking Birdwatching |

| (Courtesy: Madras Naturalists’ Society) |

|

|

A large number of Madras Naturalists’ Society members (some of them becoming members at Adyar Poonga!) descended on Preston (Ahimaz) and the Poonga at 6:45 on a late October morning. It was a surprise to find that the resident birds did not take off in alarm at the racket we made in the car park.

We were delighted to see the huge progress in tree planting and recharging of the waterholes that have happened in the past six to eight months. We look forward to playing a part in restoring the estuarine ecosystem of the area.

Preston took us around the 53(?) acres and, of course, we did not stick together, many of us struggling, but he dealt with all this with great fortitude!

Here is a list of plants, birds and insects which we saw (compiled by Yamini).

PLANTS: Cocoloba uvifera – sea grapes, Bauhinia sp., Ipomoea biloba, Vitex negundo – Nochi, Cassia alata, Cassia biflora, Terminalia ar juna, Water lily, Rauwolfia tetraphylla.

BIRDS: Dab chicks/Little grebe, White-breasted water hen, Black-winged stilts, Pond heron, White-throated kingfisher, Pied kingfisher, Cormorants, Coot, Spotted dove, Night heron, Shikra, Little blue kingfisher, Parakeets, Blue rock Pigeon, Red-wattled lapwing.

INSECTS: Peacock pansy, Lemon pansy, Common lime, Crimson rose, Common emigrant, Tawny coster – caterpillars as well, Blue pansy, Plain tiger, Danaid egg fly – female, Common gull, Castor butterfly, Cabbage white, Ruddy marsh dart, Green marsh hawk, Wandering gliders, Lady bird, Bumble bee, Coromandel marsh dart, Ditch jewel, Painted grasshopper, Male ground skimmer, Blue grass dartlet.

– Ambika Chandrasekhar

* * *

We selected the first day of the monsoon in Chennai for a visit to the Pallikaranai marsh! At the first stop we were greeted by Terns flying over the northern part of the marsh. There were more terns stitting in a line on the wire. In all, there were almost a thousand birds, mostly Whiskered terns. Cattle egrets, Indian moohen and Purple moorhen were also in plenty. The Moorhen were so fluffed up that, looking at them from a distance, one could easily mistake them for Glossy ibis! And there were these three Spot-bill ducks swimming in a convoy unmindful of the rain which was getting heavier, and it made a picture perfect scene. Ashy Prinias were calling from the Typha bulrushes and an occasional Reed warbler joined the chorus. There were Coots scattered all over the expanse of water and the Black-winged stilts were circling over the marsh, uneasily. The reason probably was the Marsh harrier, which finally landed in the grass! A lone Curlew was probing the mud with its long curved bill. Ruff with its distinctly orange legs and its somewhat smaller companion Reeve were present and we estimated their number to be fifty.

Moving to the south and east we got the biggest and the most rewarding sights of the day. There were, in the lazy and rainy landscape, about thirty Greater flamingoes feeding. They were using their specially adapted beak upside down while feeding. Another forty Flamingoes flew past. It was a great day and a special event for us when we saw half a dozen Flamingoes in the Adyar estuary in those days. But today we had seen seventy at one spot inside the city, not far from the smouldering garbage dumpyard!

There was more excitement to come. The Grey-headed lapwing which we have been seeing here only in the past few years were very close to the shore. In fact, they were so close that we were able to see the eye ring. This is a bird which looks so dapper with its grey breast band across its white belly and a yellow beak tipped with black. The Avocets, elegant in black and white plumage, and which breed in Europe and Central Asia, had selected our own Pallikaranai marsh paying scant attention to the mayhem of the burning garbage. A group of Black-tailed godwits with their long and straight bills (another of those long distance migrants from Central Asia) was busy feeding. A lone Pheasant-tailed jacana in breeding plumage landed as if to answer our unspoken wish. Shovellers and Garganey swam lazily in the drizzle and some of them joined the Coots in the mounds dotting the waterspread.

It was such a wonderful experience that I may cancel my trip to Bharatpur this winter! But where are the pelicans? We did not see even one!

– K.V. Sudhakar

* * *

Flamingoes have been seen in large numbers during October at Mudaliarkuppam near the TTDC boat house off the ECR between Mamallapuram and Puducherry (about 90 km from Chennai). There have been wonderful sights of flamingoes feeding, sandpipers, godwits, terns and other waders at close quarters. There have also been movements of the butterflies all around. The usual birds were present on the ECR roadside: Indian rollers, pied and white throated kingfishers, common hoopoe, ashy woodswallow, brahminy myna, etc. At one location just after Mamallapuram we saw a big flock of open-bill storks and white ibises foraging right on the side of the road. At Mudaliarkuppam, rows and rows of greater flamingoes posing for us, just 100 m from the shore, were a splendid sight. Several other passing cars stopped to join us as we peered beyond the flamingoes to identify the other birds. We also noticed some dull coloured young adults in the groups. Hundreds of sandpipers (common, marsh and wood), a solitary painted stork (which was in the same place when we returned after 5 hours), purple and grey herons, black-winged stilts, grebes, caspian terns, whiskered terns and some brown-headed gulls, whimbrels, kentish and little ringed plovers, godwits, red and green shanks were sighted.

– Usha Pillai, Kailash and Sripad

Back to top

|

|

Point of View Lost Sanctity |

|

|

|

I was born in Nadu Street, Mylapore, and still live in that ancient town. In those days the Mada Streets used to be clean and had only a few houses, most of them occupied by senior lawyers. Above all, the Kapaleeswarar temple looked imposing and could be seen from the Venkatesa Agraharam side, where the Indian Bank now is. The temple had a compound wall about 15 feet high and was painted in red and white symbolising a Hindu temple.

The temple tank used to be clean and the walls of the tank were also used to be painted in red and white. On all sides there were entries and we used to sit on the steps of the tank. There used to be coconut trees on all the sides of the temple and a huge well at the entrance. After the late 1960s things began to change.

The temple has enough properties and there was no need to increase its wealth. But the coconut trees were cut down and substantial constructions raised to house shops alongside the walls on North Mada Street. The well was closed with cement slabs and constructions came up on either side of the entrance to the temple. No longer could the temple be seen!

Large numbers of people used to come to the temple and sit on the sands of the temple. But the whole area inside the temple has now been parked with stones and a person cannot even walk after eight in the morning as the whole area is so hot.

The grace and glamour of the Kapaleeswarar temple have been shattered. I pray for the day when the shops will be demolished, the stone flooring is removed and the temple’s red and white walls, emphasising its sanctity, become visible all around.

Dr. R.K. Balasubramanian

Old No. 30, New No. 70,

Chitrakulam North, Mylapore,

Chennai 600 004

Back to top

|

|

|

|

|