|

The contribution of the College of Arts and Crafts to the arts and crafts story of Madras Presidency is little known but, in truth, has been immense. The College was founded in 1850 by Dr. Alexander Hunter, a surgeon in British military service, as a private institution called the Madras School of Arts. The School came at a time when the economic policy of the Government had reduced India into a manufacturer of mechanised products and had driven most Indian crafts to extinction. The trend was exacerbated by the collapse of royal courts that had been centres of crafts patronage. In a year, the School had become a centre for imitation. A lack of originality and dearth of teachers forced the Government to take it over and move it from Popham’s Broadway to its current premises in 1852. The School was then named the Government School of Industrial Arts. In consultation with the East India House and the Royal Academy, London, Hunter had the syllabus revamped. The School now had two departments: The Artistic Department, where students learnt architecture, drawing (including botanical, anatomical maps, etc), woodwork, copper engraving and pottery, and the Industrial Department where they learnt how to make tools and objects required for construction, such as bricks, tiles, etc.

The Cenotaph on the Mount Road

View of the Medical College, General Hospital and the Coovm River from near the Walajah Bridge

View on the Mount Road opposite the 1000 Lights

Tomb of Fuzeelit Onnissa Begum, the favourite daughter of the late Prince Azim Jah Bahadur, near Saidapet on the Mount Road

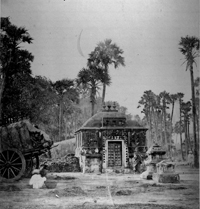

Oachen Covil near the Spur Tank

Sreevilliputoor

|

The School was headed by distinguished men of the Arts. Robert F. Chisholm, who designed most of the Indo-Saracenic buildings in Madras, succeeded Hunter. W.S. Hadaway was another. The best of them was E.B. Havell who became Principal in 1884. Unlike most of his peers and predecessors, he believed that craft produced with Indian motifs would be just as marketable in Europe as was Indian craft produced with Western-inspired themes. Havell went against the trend of asking Indian craftsmen to copy Western motifs and encouraged Indian craftsmen to teach Indian motifs to students. To implement this revolutionary concept, the School hired a wood carver from Ramnad, a metal worker from Kumbakonam, and a goldsmith from Visakhapatnam District and used their knowledge of the Shilpasastras to adapt designs and teach them to students. It was during Havell’s time that handloom weaving and block printing became important departments. For many years, the School had a stock of several hundred exquisite wooden printing blocks.

When Havell left in 1896 to take over as the Principal of the Calcutta School of Art, much of his good work was lost, as Indian art again became of little interest to the Government. There was even a proposal for the School to become a manufacturing unit of cheap aluminum vessels which had a market potential. In 1927, Rao Bahadur N.R. Balakrishna Mudaliar became its first superintendent. D.P. Roy Chowdhury, a student of Abanindranath Tagore, became the School’s first Indian Principal. He did much to bring in an international influence and inspired several students to become great artists. K.C.S. Panicker succeeded him as Principal in 1957 and, in 1961, the School was upgraded to a College. Since then, the College has produced several generations of talented artists. While the names of the Principals are recorded, the names of the craftsmen who taught the students have not been recorded for posterity, in the tradition of Indian art where the artisan seeks to live through the beauty of his work rather than his name.

Stepping into the College today is like walking into another world where time stands still. The main building is the studio and the library block. The old museum designed by Chisholm was once accessed from the road. The design incorporates stained glass, woodwork, brickwork, all examples of the fine craftsmanship of the College. Stepping into the library is a delight. Sunlight streams in from windows on either side and sheds a soft light on the floor-to-ceiling wooden cupboards filled with books. Some of the furniture is new, but the old tables, probably made in the College, give a rough idea of the beauty of the work of the College. The treasures of the library include:

1. Books on textile and architectural patterns.

2. A series of 17 volumes of photographs taken by students of the College.

3. 11 volumes of photographs taken by a Capt. Lyon and one by Capt. Linnaeus Tripe.

In this article, I focus on (2) and (3).

Around 1855, Hunter included photography as a subject. The introduction of the subject created a lot of interest in other art colleges in India (all of which are younger than the Madras institution). The Asiatic Societies in Calcutta and Bombay as well as design schools in London were keen to have copies of the photographs.

The photographs taken by the students of the College were preserved in volumes bound in “chrome leather, tanned, dyed and finished in the School of Arts – 1904” and are still in the library of the College. They are titled ‘School of Industrial Arts, Photography Class, 1862-1876’. A label in the volumes records their binder, Rajaruthna Nayagar, No 12 & 13 Putha Perumall Nayagar Street, Mannarswamy Kovil, Mount Road, Madras.

The photographers have predominantly focussed on Madras (41 plates) and Mahabalipuram (61). The locations in Madras are virtually unrecognisable today. Photographs of the Thousand Lights area in Mount Road show small muddy lanes with thatched houses on either side where there are more trees than people. Another photograph is of a bamboo market in Mount Road. Saidapet was another stop for the students. The photographs there were predominantly of animal husbandry. A photograph titled Oachen Covil, Spur Tank Road, shows a small temple with a bullock cart in front and a grove of palm trees in the back.

Lyon’s lament

Accompanying the photographs are printed cap-tions. As a conclusion, Lyon warns future travellers in the late 19th Century:

“Before leaving Madura, it will be well for the traveller to ponder seriously over the mode of travelling he intends adopting. The remarks hitherto made, as already stated, apply only to the high roads which, disgracefully bare as they are, still become beautiful by comparison with the cross-country ones which will now have to be traversed. No bungalows either will now be found, and consequently the traveller must provide himself with tents, which had better be purchased in Madras and sent on before. It is hardly possible, without even greater discomfort than is actually bearable, to manage in that climate with one tent. Two therefore should be procured, one of which should always be kept in advance, and if there be no hurry, and riding be selected as the mode of travelling, with good servants accustomed to tent life, there is no hardship whatever to be encountered; on the contrary there is no pleasanter life than marching, as it is called, with tents in the plain of India. It is the mode of travelling adopted by Collectors of districts, who go with their wives and children and tents for the four winter months of every year while they make their tour of their respective districts.

“In the first place it will be found by experience almost impossible to persuade the native servants to start at the proper time, as especially if they are Hindoos an hour or more will be wasted in “eating rice” after everything else is packed and ready. Again, the bullocks are never found ready at the different stages. Another hour is often lost in enduring to find where they are located; and thus the sun will be up, and the great heat will have commenced before the resting place is reached, if long stages are attempted. There is one other commodity with which the traveller will do well to provide himself before undertaking such a journey, which is a firm determination to take philosophically the contretemps of every sort and kind which must inevitably happen daily, if not hourly, to try his temper, to say nothing of the carelessness, dilatoriness, utter disregard of time, and often cool impudence of his Hindoo servants which it must be confessed are often sufficient to vex a saint, let alone an Englishman, vegetating under the tropical sun of India.”

|

The photographs of Mahabalipuram focus mostly on the five rathas and inscriptions. Two photos that give a glimpse of the town are one taken during Lord Napier’s visit, which shows the many camels used for the trip, and a street of thatched houses behind the sculpture of two monkeys. The 19 Kanchipuram plates focus on the Varadaraja Perumal temple and the Ekambareswarar temple. The street view of the Ekambareswarar temple gives us a sense of how imposing the temple would have been in ancient times when all buildings around would just have one or a maximum of two stories. A particularly fine photograph of this temple is the aerial view.

There are 61 photographs of the Nilgiris including pictures of Coonoor Bazaar from Woodcote House, Smiths Hotel, Balaklava House, Benhope Estate, Glenmore, St John’s Church and a waterfall near Prospect Lodge. There are several photographs of the Todas, Badagas and Irulas, all posed unnaturally.

Other photographs are of Vellore (16), Tirupati (7) spelt Tripati and showing hardly any devotees, in stark contrast to today’s scene, Chendragherry (2), the last stronghold of the Vijayanagar Nayaks, Humpey (Hampi) (6), Veerinjipuram (8) and Taramangalam (8). A notable feature of the pictures is the temple tanks which in every photograph are full and well maintained. The thresholds and mandapams of many temples, however, are covered by a layer of sand that makes it impossible to see the original flooring. Other places photographed were Tinnevelli (1), Chidambaram (6), Thanjavur (7), Rameswaram (3), Thiruvannamalai (2), Cenji (1), Srirangam (1), Cocanada(1), Kalugumalai(1), Ahobilam (18), Thirukazhukundram (5) and Madurai (19). All photographs are titled in beautiful, cursive writing with black ink at the bottom of each plate.

The Tripe and Lyon volumes are larger than folio size and were bound in 1904. In some volumes, the captions have been cut from the original and pasted at the back of the photographs. These volumes must have been prohibitively expensive and, apart from the set with the Madras Literary Society, this is probably one of the few in India. Happily, all the photographs taken by Tripe can be viewed online with their captions in the collection of the British Library. These books are an important asset to the Library since, within just a decade of its invention in 1839, photography was practised in Madras and had become a subject in 1855 in the Madras School.

Tripe’s photographs are important for their documentation of life in his times. In the second half of the 19th Century, the British began to take an interest in both archaeology and epigraphy and they began to appoint photographers to take photographs of important monuments and inscriptions on their walls. Inscriptions of temples like the Brihadeeswara, for instance, had already been scribed in parts by Sir Walter Elliot (founder of the Madras Photographic Society in 1856) in the 1830-40s with the help of his scribe Viswambara Sastri.

Tripe had joined the army in Madras in 1839. He had taken some photographs of Belur and Halebid in Karnataka while on a personal visit. In 1856, he was the ‘Official Photographer’ of the British Mission in the court of Ava where he photographed 120 views. The College has a volume of photographs that record art objects displayed in an exhibition in Burma. Could these be the work of Tripe?

Tripe was appointed the photographer for the Government of Madras in 1856. His priority was to photograph objects in the Presidency that were of interest to the “Antiquary, Architect, Sculptor, Mythologist and Historian.” In 1857, he did not seem to have done much except teach the subject in the School. Tripe then toured the Presidency (1856-60). He was assisted by C. Iyahsawmy, a talented photographer himself and a teacher in the School whose works have disappeared. Tripe has stated that he wanted to record these objects before they disappeared and his photos do bring back a sense of nostalgia for anyone, regardless of whether they have seen the subject or not. He was fascinated with temples, their size and role as focal points in the villages. Very few of his photos, except those in Pudukottai, have people; he seemed to have relished the architecture more. The captions for the photographs, however, have a wealth of mythological information and a yearning for the great past that had preceded the British (something that was an inconvenience for the British). Unfortunately, the financial crisis after 1857 forced the Government to stop funding Tripe. In 1859, he was asked to sell his equipment and wind up. By 1870s his work was forgotten and remained so till 1970s. He published eight volumes covering Madura, Tanjore, Trivadi (i.e. Thiruvaiyaru), Pudukottai, including Thirumeyyam, Rayakottah and other places in Salem District, Srirangam and Trichy. There are also stereographs (taken with a binocular camera) of Trichy, Tanjore and other places in their neighbourhood (70 prints). Tripe died in Plymouth, where he was born too.

Captain Tripe’s photographs are bound in one volume. Published in 1858, Parts I, II and III are bound together. Some of the photographs are missing, but those that remain show the sensitivity and appreciation Tripe had for Indian architecture.

His photographs of the Meenakshi Amman temple and of the Tanjore palace are evocative of an age that we have lost forever.

Captain Lyon’s photographs cover Secundrmalie, as Tiruparungundram was known. Lyon laments the disfiguring of pillars by whitewash, rude masonry and paintings of the “vulgarest descriptions”. Fortunately he was not to see how 21st Century devotees have taken this to lower depths.

The volume on Sri Rangam, Jambukeshwara temple, Thirukoshtiyur, has a particularly beautiful aerial view of Sri Rangam taken from the south side “Mottai Gopuram” that shows the beauty of the town. Another volume covers Madura. Lyon remarks that even in those days horseback travel was the best, followed by bullock carts, since it was difficult to get palanquin bearers. Most of the photographs of Madurai are of the Thirumalai Nayaka’s palace which was then used as a court by the British. He remarks that the green parrots were in “immense numbers … and (their) shrill screams can hardly be supposed to contribute much to the deliberation of the court.”

Next he visited Avudayar Koil, Peroor and Tarputry (Tadapatri?). Lyon recommends a short detour to the Nilgiris from this journey. He seems to have stayed in

Mr. Sylk’s house in Ooty or Coonoor.

A volume on Srivilliputoor-Kazhugumalai-Tirunelveli devotes many photographs to the temple car of Sriviliputtur. Lyon notes that the ratha was sponsored 25 years before his photography and has a staircase inside it. While camping at Kazhugumalai to photograph the Jain images, Lyon complains of white ants.

From Mysore, Lyon did a trip to Hampi, Badami, Pattadakkal, Halebid, Srirangapatnam, Shravanabelagola and Belur. His photographs of Hampi show most of the buildings buried under sand and overgrown with weeds.

This is a collection of photographs warranting a wider viewing. Dare we hope for a

public exhibition during Madras Week (August 16th-23rd) this year?!

Note: All pictures are courtesy the College of Arts and Crafts. The captions are as recorded on the photographs.

|