|

A key settlement of the Dutch in the 17th Century, Pulicat a thousand years earlier was an important settlement of the Chola Empire. It later witnessed an influx of Muslim cultures. It was a Portuguese settlement and also briefly experienced Vijayanagara glory. The Dutch East India Company transformed Pulicat into a flourishing textile export centre and it established a major gunpowder factory.

Detail of the oriental column on the Periya Jamiya Pallivasal. |

Recently, the Dutch, in a mission to revive the past glory of one of their earliest Asian settlements, have helped bring out Pulicat and Sadras – A Confluence of History, Culture & Environment* in a bid to focus attention on the shared heritage of the Dutch and the Indians. The book highlights the shared cultural history of India and The Netherlands and narrates the historical significance, past glory and the present condition of the towns.

The earliest historical reference to Pulicat is found in the inscriptions at the Tiruppalaivanam Chola temple, wherein there are references to Pulicat under such names as Payyar Kottam, Puliyur Kottam and Pular Kottam. It was later, under the direct rule of the Vijayanagara emperors, that it underwent a series of name changes. For instance, in 1422 it was renamed Anandarayan Pattinam by Devaraja II and in 1522 it was called Palaverkadu by Krishnadevaraya, a name still used today.

Pulicat was an important Vijayanagara port for the export trade of the Coromandel Coast. The principal exports from Pulicat to the Burma region were textiles produced on the coast and red yarn produced in the Krishna delta. Major Burmese imports included gold, rubies, timber, tin, ivory and copper. Imports from the Indonesian archipelago included spices, different woods, Chinese silks and non-precious stones.

Pulicat minted its own coins and pagodas at a mint established as early as 1615 in Fort Geldria, the Dutch fort garrisoned by ninety people. The Dutch employed local Telugu merchants in Pulicat as well as the Muslim trading community, the Lebbai, who were boat-builders. Pulicat’s gunpowder factory became the main supplier of gunpowder for the eastern territories of the Dutch and was of major importance to the Dutch East India Company from the early 1620s to the late 1650s.

The textile trade in Pulicat, based on locally produced cottons with chequered pattern or stripes, was renowned. The famed Palayakat lungis originated from here and were used for sarongs in Ceylon, Burma and Southeast Asia. The British made the same cloth famous under the name Madras Checks. Pulicat textile manufacturers had a thousand handlooms at the peak of the trade.

A view of the new cemetery from Northwest side. |

Pottery-making, woven palm leaf handicrafts and fishing are Pulicat’s mainstay today.

The Dutch influence can be seen in the architecture and the cultural leanings in Pulicat’s churches, temples and housing.

Inspired by the renaissance style architecture, St. Antony’s Church still stands. It has features of Tuscan style architecture as well. The Our Lady of Glory Church is the other church in Kottai Kuppam and is older, dating to Portuguese times, early in the 16th Century. It is Gothic in style. It has a stone slab at its entrance installed by a Peter Paul Flagman.

Kottai Street, where the Dutch merchants had their residences, was one of the busiest streets of old Pulicat. Except for some walls which are now being scavenged for materials to be used for new buildings, none of the other features of the street exists today. An old Dutch building facing the sea, that could have been used as a port office, functions as a storage complex. This building is one of the few Dutch buildings still left in Pulicat.

The only major addition to Pulicat by the British was the lighthouse, built in 1859. Its main purpose was to warn ships at sea of the Pulicat shoals and was not for port facilities. Today, the lighthouse station is separated from the Pulicat town by a seawater channel. The old lighthouse stood close to where the present lighthouse tower was built, but it was dismantled after the new one was built. It was a 20m high, brick masonry circular tower with black and white bands. The present lighthouse tower was constructed during 1984-1985.

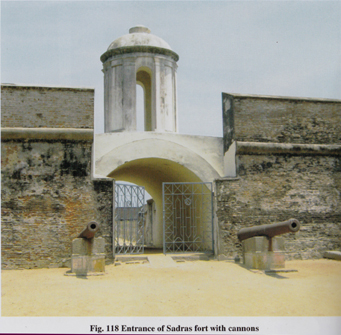

Entrance to Sadras Fort |

Two cemeteries of historical interest – the old cemetery used before 1656 and the new cemetery used after that – are to be seen in Pulicat. The old cemetery in the northwest corner of Kottai Kuppam has several old tombstones but is inaccessible owing to thorny overgrowth. The new cemetery is in the southwest corner of Fort Geldria. It houses 77 graves with detailed carvings on their tombstones. Two of the graves are topped with obelisks.

Traditional temple architecture is reflected in the various temples in Pulicat. Unfortunately, most of the temples have lost their traditional character due to various additions. The Adi Narayana Perumal temple and the Samayaeswarar temple are the largest temples in the town. Of the three other temples, two are in ruins today. The Samayaeswarar temple has undergone irreversible changes such as reconstruction of the main vimana and addition of figurines and arched niches above the mandapam. Another feature of this temple is a small, stepped well used to draw water.

The several mosques and the Muslim residences attest to a long Muslim presence in Pulicat. Between the Kottai Street and the mosques are the residences of Muslims; these residences still retain their traditional character.

| • Sadras is 17 km south of Mahabalipuram, between the Kalpakkam Nuclear Power Plant and its township.

• It was a flourishing weavers' settlement during the medieval period (10th to 16th Centuries). Exports included muslin cloth, pearls and edible oils.

• The Sadras fort, cemetery, secret chambers, and warehouses are historical structures that survive.

• Excavations at Sadras in 2003 led to the discovery of many buried artifacts, such as glass arrack jars, Gouda smoking pipes etc.

• The church has been remodelled completely. The cemetery had several 18th Century tombs, but due to lack of protection, only three of them are to be seen today. |

The Periya Jamiya Pallivasal, the Chinna Pallivasal and Keela Pallivasal are the main mosques of Pulicat. The Periya Jamiya Pallivasal mosque’s structural system is the same as that of the temples of the time, but is architecturally based on Islamic laws. Two interesting featues of the Chinna Pallivasal mosque are the sun-dial installed in 1914 and a marker used to ascertain time before the sun-dial was installed. A unique feature of the century-old Keela Pallivasal mosque is that it shares a compound wall with the Samayaeswarar temple.

The book also highlights the importance of Pulicat Lake and regrets the depletion of its resources. The shallow lake is known for its diversity of aquatic birds and is an important stopover on migration routes. It is considered the third most important wetland on the eastern coast of India.

The book factually details the state Pulicat, the former Dutch settlement, is in today, an almost sleepy state, it might be said, but does not offer suggestions on how it can be restored or brought to life again.

The potential for its development as a heritage town is not looked at.

* Brought out for the Embassy of The Netherlands by Anamika Architects with the help of the students of the School of Architecture and Planning, Anna University.

|