| (ARCHIVE) Vol. XVIII No. 15, november 16-30, 2008 |

|

| The boldest Judge in Madras |

| (By Randor Guy) |

|

|

From its inception in the 19th Century, the Madras High Court, one of the three oldest in the country, has produced several legal legends who have left indelible footprints in the sands of time. Among the many Indian luminaries was Sir Mutha Venkatasubba Rao.

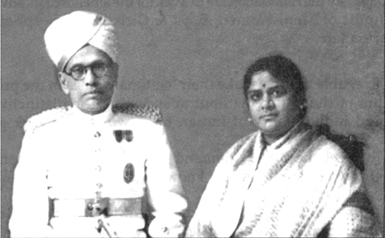

Sir Mutha Venkatasubba Rao

Sir Mutha and Lady Andal Venkatasubba Rao |

Besides his intellect, knowledge of Law and manners, Sir Mutha was noteworthy for his dash, dynamism and willingness to stand up to the European powers-that-be of the day. Indeed, V.C. Gopalratnam, the well-known lawyer who had appeared before Sir Mutha in court and had also worked with him earlier when he was a lawyer, described him as “the boldest judge who ever walked the corridors of the Madras High Court.”

During his tenure on the Bench he demonstrated these characteristics several times. As in the following instances.

In Sir Mutha’s day electric fan comfort was not as common as it became later. The High Court building had no fans at all, judges and lawyers being cooled by ancient punkahs. As the High Court buildings were by the shore of the Bay of Bengal, the natural sea breeze provided a considerable degree of comfort in a humid town.

Sir Mutha was allotted as his private chamber a room which had many windows opening on to the beach. A British judge coveted this chamber and, one morning, occupied it well before Sir Mutha’s arrival. When Sir Mutha walked in and saw the British judge in his chair, almost ignoring the lawful occupant entering the room, Sir Mutha stalked out and sent a note to the Chief Justice, another British judge, telling him that he was leaving for the day and would not return to court to discharge his duties until he was given back his room, where he had his files, legal papers and judge’s robe. He then went home. The poor Chief Justice was at a loss for a while, but knowing Sir Mutha’s temperament he persuaded his brother British judge to vacate the room for Sir Mutha.

Sir Mutha officiated twice as Chief Justice, when British Chief Justices went home on leave following the summer vacation. It was a rare appointment at a time when the British generally did not appoint Indians to the post of Chief Justice even for a short period.

During one such period, when he was officiating as Chief Justice, the selection of District Munsiffs came up for execution. In those days, the choice was left entirely to the discretion of the Chief Justice. Sir Mutha, strictly following the procedures, arranging interviews and getting opinions about the candidates, selected 20 advocates as District Munsiffs and sent the list to the Governor for his approval. While the list was under consideration, the Chief Justice returned from Britain and was shocked to find that his acting Indian counterpart had finalised the selection and sent the list to the Governor for confirmation. Feeling insulted, the Chief Justice called for fresh applications and, in due course, sent his list to the Governor, stating that Sir Mutha had no authority to appoint Munsiffs, for he was only the Officiating Chief Justice. When the matter was referred to him, Sir Mutha sent the Governor a curt reply, stating that if his selection of Munsiffs was invalid, then all the judgements and orders he had delivered and passed during the period in question should also be declared invalid! The stunned Governor had no answer and to prevent a crisis, he appointed all the candidates from both the lists. So, that year, forty Munsiffs were appointed.

Mutha Venkatasubba Rao was born on July 18, 1878 in Cuttack (which was then in the Madras Presidency; Orissa came into existence only in early 1934). After graduating from Madras Christian College, he took his Law degree in 1902 and served as apprentice in the chambers of Sir Calamoor Kumaraswamy Shastriar. In July 1903, Venkatasubba Rao set up practice as an Original Side vakil (as Indian lawyers were then called, being considered a rung below British advocates) and soon garnered a considerable practice. In 1921, he was appointed a judge of the Madras High Court which raised many eyebrows, because lawyers, especially those from Mylapore, thought that Mutha did not have enough knowledge or experience of the Appellate Side of the High Court. However, within a short time he proved them all wrong.

He served as judge for 17 years and retired in 1938 after being knighted. During his days on the Bench, he sat in judgement over hundreds of appeals. Perhaps the most sensational was the case in which the Maharajah of Vizianagaram sought the custody of his minor children, who were ostensibly being sent to England for their studies by the Maharani. In a sensational judgement, Justice Venkatasubba Rao ordered the captain of a ship docked in Bombay not to sail with the children of the Maharaja. Such an order had never been given in the history of the Indian courts!

Many in the legal profession have earned millions, but few of them have chosen to serve society by sacrificing their wealth, time, and energy for the uplift of the downtrodden. He and his wife Lady Andal Rao, whom he married when she was a young widow – which created history in its own way in those days – founded the Madras Seva Sadan, which runs several schools and charitable institutions to this day.

|

|

| Of billboards, buntings, posters and graffiti – a Mauritian lesson |

| (By V.S. Ramana) |

|

|

Chennai’s citizens – and those of many other Indian cities – are regularly mute spectators to the utter disregard shown to aesthetics and cleanliness in the cityscape by people who should know better. Barring Ahmadabad, I have not seen any city in India where people have spared the walls, poles, or electric/telephone junction boxes! Mr. Modi’s Ahmadabad is so clean and different. (I used to live there in 1994-96 and what a simple town it then was. How it has transformed itself today!)

A drive by political leaders some miles beyond the city is reason enough for our roads to get adorned with cut-outs that depict the leaders in a variety of postures and ward veterans offering salutations in typical ‘namaste’ postures, buntings being hung here, there and everywhere, and party flags fluttering on concrete dividers. These spring up overnight! All this only causes further damage to the already poor infrastructure in the city. But, then, it is only the taxpayer’s money!

Safety, too, takes a back-seat! A streamer or a bunting may strangle someone who jumps across the kerb. A flag pole or an 8x2 feet framed vinyl frame may fall and kill the driver of a two-wheeler. But who cares?

Chennai has banned unauthorised hoardings, but it seems to be encouraging any and everyone to make ‘bamboo hoardings’ over pedestrian walkways or even across traffic islands. We still want to be able to call our city ‘Chingara Chennai’ – and on this the perpetrators are truly beyond the political divides – but be it actor or politician, Godman or educational institutions, they all feel they can decorate and damage public property in the grand manner. Even those running roadside temples feel they have the right to dig and despoil any newly-laid stretch of road. All the 12 months see this ‘destructive initiative’ in this the 21st Century!

A recent visit to Mauritius revealed a marked difference. It made me ashamed of Chennai. It will do the same to any sensitive Indian living in urban India.

Here is how Mauritius went about it.

Driven by the Deputy Prime Minister Xavier-luc Duval (who is also the Tourism Minister), the entire nation is now fighting such menaces as billboards, buntings, posters and graffiti.

The campaign is based on a simple logic: “Posters create visual pollution, and people need to understand that it is easy to stick them, but not so easy to remove them.” The Government, responding to the Minister’s call, launched a week-long campaign against illegal posters. The campaign was called “Décoller, Pas coller” (Easy to stick..but tough to pull it off!). Thousands of students, scouts, district councils and municipalities, hundreds of trucks, and millions of gallons of water in tankers were mobilised during the week. And by the end of the week, posters and other eyesores had disappeared in the country. Then, strict laws were enacted to prevent the menace on a sustained basis.

“Mauritius is a beautiful island. It has very little other resources. Beauty alone will help our nation to gain Rs. 48 billion from tourism this year. So, let us keep our cities clean,” emphasises the Minister. And the Mauritians have gone ahead to do just that with PRIDE!

HellOOO Indian cities, citizens… are we listening? Is there any inspiration in that perspiration?

|

|

| Why seminar on a notified Master Plan? |

| (By A Staff Reporter) |

|

|

Government departments certainly do some curious things to confuse the public. The latest instance of this has been by the Chennai Metropolitan Development Authority (CMDA). Its Second Master Plan for the development of Chennai till 2026 has already been notified by the Government after consultations with the public and it was made clear that the Plan was final. But a couple of weeks ago the CMDA organised a seminar to discuss the Plan. Why? Particularly when it was made clear during the inaugural address itself that the Government was not willing to make any further changes to the Plan, no matter what recommendations emerged from the seminar.

The points that were discussed are, however, worth noting, for they highlighted the areas in which the entire plan was inadequate and needed to be improved. Some of these are:

1. Making the zonal and regional development plans a priority: The earlier master plan, which was made over 30 years ago, saw detailed development and implementation in only 56 out of the 96 zones that it covered. In the light of this, it is absolutely necessary that this master plan results in regional plans on a priority basis. But at present the Government has not set any deadline for this. It is vital that plans are made early, as several areas are bursting at the seams with unplanned development.

2. It was felt that the Master Plan has no detailed thought on how to handle drainage and waste disposal. The continued use of Perungudi and Kodungaiyur as dumping yards despite several protests from locals has not spurred Government to take action and look at modern, pollution-free methods of waste disposal. Even the basic step of segregation at source has not been implemented. Those who attended the seminar also pointed out that a master drain network should be worked out by the Chennai Metropolitan Water Supply and Sewerage Board (CWSSB), the PWD, and the CMDA.

3. The Plan has not demarcated Pallikaranai as a reserve forest and, so, the swamp is subject to development. Whatever has been done in the past has resulted in problems of flooding during the rainy season. It was recommended that a canal be built to drain the surplus water from the marsh to the sea.

4. The importance of preventing any further development in the Red Hills area was stressed. As this is the prime source of water for the city, it was emphasised that this area should be out of bounds for development.

5. Given that the Master Plan talks all the while about making the city people- friendly, it has really not addressed the issue of affordable housing and how it plans to bring this about. In fact, no thought has been given to this.

6. Nothing has been done towards the listing and protection of heritage buildings. Further, the recommendation on the Transfer of Development Rights that the Master Plan contains has no teeth, as it fails to explain how this will translate into reality. As a consequence, the city’s heritage, both built and natural, will remain under threat.

7. It was evident that even other departments of the Government were not very clear or happy with what had been notified. For instance, the Police complained about the inadequacy of parking space norms and the Housing Departments asked for greater clarity.

Given such feedback, it is most surprising that the CMDA has categorically stated that no further modifications in the Master Plan were possible. Even here, there were contradictions. The Minister-in-charge, in his valedictory speech, said exactly the opposite and agreed to incorporate what was feasible. With such contrasts and conflicts, can the Master Plan be effective?

|

|

| Oriental studies, Sappers & medical research |

|

(an annotated bibliography from the Web) compiled by

Dr. A. Raman

|

|

Institutional History

Otness H (1998): Nurturing the roots for Oriental studies: the development of the libraries of the Royal Asiatic Society’s branches and affiliates in Asia in the Nineteenth Century. International Association of Orientalist Librarians (IAOL) Bulletin 43, 9-17.

The Madras Literary Society was founded in 1812. It became an auxiliary of the Royal Asiatic Society (RAS) in 1830. MLS published Transactions of the Literary Society of Madras up to 1827. The title Madras Journal of Literature and Science was suspended in 1866-1877 and again in 1882-1885. Its title was the Journal of Literature and Science (Volume 1) from 1886.

The Madras Sappers’ Association (no date).

www.madras sprsassociation.org/history.htm.

Temporary companies of Indian Pioneers were raised from locally available manpower on an ad-hoc basis. They were used to develop tracks for movement of gun carriages, for digging trenches and saps, and clearing hedges for the advancing armies.

The companies were disbanded as soon as the task was completed. The fact that they were neither armed nor trained to fight and abandoned their tasks on hearing the first shot, thereby creating all-round panic, was not lost upon Lt J. Moorhouse, an Artillery officer, in-charge of the Commissariat (predecessor of the Army Service Corps), whose job it was to organise the movement of stores. Moorhouse wanted the Pioneers to be in uniform and subjected to army discipline. Two regular companies of Pioneers were thus sanctioned on September 30, 1780. (The date is now regarded by the Madras Sappers as their Raising Day.) Moorhouse can thus be considered the ‘Father of the Madras Pioneers’.

Industrial History

Anonymous (2008) Madras cotton. www.stitchnsave.com/Madras_Cotton.asp.

The Madras (fabric) is a lightweight material with patterned texture, generally derived from cotton, but also supplemented with either rayon or silk. The Madras fabric has a high thread count, with colour background with stripes, plaids, checks or designs on it. The Madras originated in Madras, India. Madras is also a city in Jefferson County, Oregon, originally called ‘The Basin’, and renamed ‘Madras’ in 1903 after the cotton fabric originating from Madras, India. In the 1960s, a popular fabric was called ‘bleeding madras’, which used dyes that were not colourfast in a typically plaid design, causing the colours to bleed and fade each time it was laundered so that a new look resulted.

Medical History

National Cataloguing Unit for the Archives of Contemporary Scientists (NCUACS), University of Bath (UK) (no date). History of science – connexions. www.bath.ac.uk/ncuacs/Connexions5.htm.

Archived information refers to John Cunningham’s (1880–1968) medical researches in India (on the bacteriology and immunology of relapsing fever, and the major programme on the treatment of rabies, which he instituted on his appointment as Director of the Pasteur Institute, Kasauli). There are also records of the work on vaccine lymph carried out at the King Institute, which was the principal research laboratory and vaccine depot of South India. Also included is archived information relating to Harold Miller (1909–1995), who was associated with the International Cancer Centre, Neyyoor, and the Barnard Institute of Radiology, General Hospital, and Madras Medical College, Madras (1965–1994).

Arnold D. (2003) Plurality and transition: Knowledge systems in Nineteenth Century India. Princeton History of Science Seminar (October 24, 2003). www.princeton.edu.

References to the report of the Madras Committee on the Indigenous Systems of Medicine (1923), the work of botanists such as Buchanan, Wight and Hooker, on plant structure, and microscopy by William Griffith of the Madras Medical Service in the early 1840s, and into their commercial uses are found. Also reference to sighting of the steam vessel Enterprise manoeuvring offshore ‘for the gratification of the public’ as requested by Sir Thomas Munro (Governor of Madras) in April 1827.

Anonymous (no date). Dharampal, Gandhian and historian of Indian science. marsh.in/html/dharampal/dharam pal.htm.

Dharampal found that for long periods in the late 18th and the 19th Centuries, the tax on land in many areas exceeded the total agricultural production of very fertile land. This was particularly so in the areas of the Madras Presidency (comprising current Tamil Nadu, districts of coastal Andhra, some districts of Karnataka and Malabar). The consequences of the policy were easy to predict: in the Madras Presidency, one-third of the most fertile land went out of cultivation between 1800 and 1850. In 1804, the Governor of the Madras Presidency wrote to the President of the Board of Commissioners in London: “We have paid a great deal of attention to the revenue management in this country ... the general tenor of my opinion is that we have rode the country too hard, and the sequence is that it is in a state of the most lamentable poverty. Great oppression is I fear exercised too generally in the collection of the Revenues.”

Administration History

Mustafa M. (2007) The shaping of land revenue policy in Madras Presidency revenue experiments – the case of Chittoor District. Indian Economic & Social History Review 44, 213–236.

There were a number of systems of settlements in Madras Presidency when the East India Company assumed administrative charges at the end of XVIII Century. The Company government did not know which system was suitable and should be adopted for the whole of the Presidency. It initiated permanent settlement in 1802 in some areas, and found it unsuitable to be applied to other regions. Thus, it began a series of experiments in different districts to find a suitable system of settlement. These revenue experiments finally led the Company government to adopt the ryotwari system in many regions. It is these revenue experiments that the present article examines in relation to Chittoor district, and brings out the factors responsible for changing government policies during the period of experiments. The study shows how the settlements made with different types of landlords led to the formation of separate groups in rural areas and, in turn, planted the seeds of factional politics in the later period in the present Rayalseema region, which roughly coincides with the erstwhile Ceded Districts. It also throws light on the policy of discrimination against the cultivators, which led to deterioration in the conditions of these people.

|

|

| The Wiele and Klein collections |

|

|

|

(Continued from last week.)

By 1920, photographs by Wiele & Klein were reproduced in numerous guidebooks and reports. The studio executed orders of all sorts, amongst which was an assignment to photograph the leading members of the Theosophical Society in Adyar (Annie Besant, C.W. Leadbeater, Jiddu Krishnamurti, and George Sidney Arundale).

Parry’s Corner in the late 1890s as seen by Wiele & Klein (Courtesy: Vintage Vignettes)

|

Erwin Drinneberg, Theodor Klein’s brother-in-law, published in 1926 a book titled: Von Ceylon zum Himalaja: Ein Reisebuch. Mit 41 Originalaufnahmen des Verfassers (From Ceylon to the Himalaya. A Travelogue. With 41 original photographs by the author). Drinneberg dedicates this book to his sister as well as to his brother-in-law. He does not, however, mention that almost all the photographs in his book were taken NOT by him but by Theodor Klein and his partner, Peyerl. According to Elisabeth Drinneberg, who married Erwin Drinneberg in 1920, the first journey of Drinneberg to India took place in 1909-1910. In 1929 the Drinnebergs visited Madras on their return journey from a round-the-world trip. Elisabeth Drinneberg, who died around 1970, bequeathed the photo collection which they had brought to Germany to the Volkerkundemuseum Heidelberg.

There is another collection of unmouted photographs of a German traveller who, in early 1928, made a journey to what was then British India and the Dutch East Indies. The collection surfaced near Chemnitz in Saxony. Many of these photographs have a stamp on the back “For Permission To Publish Apply to / Valeska Klein, Photographer, Late Of / Wiele & Klein, / 11, Narasinghapuram Street, / Mount Road, Madras,”... When Ordering Further Copies / Valeska Klein, Photographer, Madras.” (all in capitals).

The last years

World War II brought to an end the German ownership of Wiele & Klein and Klein & Peyerl respectively. At some point, the studio was acquired by John Vetteth and lived on as “Klein & Peyerl”, an enterprise that produced some of the finest lithographs in India, until the early 1980s. The last postal address was: 135 Mount Road, Madras 600 002.

Major collections of photographs by Wiele & Klein are in the British Library (Asia Pacific and Africa Collections), which list 78 photographs by Wiele & Klein, most of which were taken either in the late 19th Century or during the

first Coronation Darbar in Delhi in December 1902-January 1903, and a few taken in 1913-1914.

The Volkerkundemuseum der J. & E. von Portheim-Stiftung in Heidelberg, Germany, has some 500 silvergelatine prints and lantern slides by Wiele & Klein, which were bequeathed to it by. Elisabeth Drinneberg in the 1970s.

And the third large collection of glass plate negatives is with Vintage Vignettes in Chennai, their acquisition of the plates being another story altogether.

(Concluded)

|

|

|

|

|