| (ARCHIVE) Vol. XIX No. 6, july 1-15, 2009 |

|

It’s time for a real

Indian architecture

|

| (By P. T. Krishnan) |

|

|

Driving over the Kottur-puram Bridge recently, I noticed a huge hoarding, with pictures of fancy glass buildings, asking viewers to guess whether the vision they were being asked to admire was in Oslo, Stockholm or Helsinki. The answer, meant to shock and awe the public, was ‘No, it is in Chennai!’ This, and many others like it, say it all – Architecture, in the minds of many, is no longer something to be cramped in its style or expression by geo-cultural realities. In due course, it may break free of all earthly realities (gravity notwithstanding) and then we can all feel humbled by the presence of buildings that look like spaceships.

How did all this come to pass? We are all aware that the modernist movement which spawned the international style of the 1950s was embraced by newly independent nations with great fervour. These were nations emerging from the shadow of colonialism to a modern identity seeking a new social order and architectural expression free of their oppressive past. With the traditional and cultural influences taken out, its stark geometric forms soon came to be seen as lacking in humanism and the sterile public spaces it created were alienating, to say the least. Even so, geographical influences were carefully kept in sight, as seen in the works of Jane Drew and Maxwell Fry.

A modernist off-shoot, Tropical Architecture made its appearance in India and several African countries during this period and successfully addressed climatic factors through the use of passive systems integrated with building design. So how green or how new is the hyped-up ‘green’ building of today?

The Post-Modernist effort to somehow link architecture more closely with people and cultures took many different forms with a revival of the regional vernacular in several areas, a rediscovery of the ‘Raj’ architecture, and the unabashed use of colour (a no-no to many modernists) as a form of expression in building design. Architecture has always followed other art movements in its expression – modern, post-modern, humanist, de-constructionist etc. – and could always be viewed as something belonging to a culture or regional ethos. But the current struggle with new-found freedoms, brought on by the availability of a slew of high-tech products and a liberalised economy, defies interpretation.

The defining feature of post-independent India, before liberalisation, had been a sense of austerity and a life accustomed to shortages. Decision-making was simple, because choices were limited and available resources had to be stretched to fulfil just your basic needs. The architecture of this period, however, was highly focussed and extremely innovative, something to which the works of some of the Indian Masters of this period will stand testimony. Further, we were on the verge of a body of work which could definitely have been classified as ‘Modern Indian’.

Suddenly we shifted gears and moved into a system of plenty brought on by so-called globalisation – a shift from a socialist economy – to a consumerist economy with free-flowing credit. This paradigm shift, which made available multiple choices and, literally, unlimited credit to the consumer, made decision-making a complex process. To be able to evaluate several options and make what can be called an educated choice required access to information and skills not hitherto considered essential. Architects needed to re-train themselves to remain relevant and fulfil their social responsibilities as creators of rapidly growing cities and towns.

Instead of engaging in this complex and multi-dimensional process, we have fallen prey to the worst aspects of globalisation – a compulsion to mindlessly imitate Western symbols of progress – in a desperate bid to cover up the reality. Where we cannot provide even basic sanitation to substantial sections of our city, we spend lavishly on exclusive development in selected sectors as symbols of our rapid progress. But, then, we as a nation seem to be always satisfied with symbols rather than the real thing. Our democracy is symbolic. We have all the necessary institutions that constitute democracy, but they exist only as symbols. We know that in reality they function in a corrupt and Byzantine manner denying citizens their basic rights.

In such an environment, and through our lacking in self-esteem, we have allowed our minds to be colonised by global (read Western) business, and stand converted into a market to indiscriminately consume their products – something which even two hundred years of foreign domination could not achieve. Big businesses in their effort to align themselves globally and seeking to re-package themselves in a way that can be accepted by their peers elsewhere insist on imitating design styles of the great commercial centres of the world, disregarding the psycho-geographical context altogether. What is the rationale behind an IT major imitating the glass pyramid of the Louvre Extension in Paris at its Bangalore campus with roadside teashops forming the foreground? When cold-climate designs are reproduced in the tropics, the energy required to sustain them increases several-fold. Knowing this, we still indulge in this form of imitation because India Inc. demands it. If this kind of mindless imitation continues, architects in India will find themselves being replaced by their ‘foreign’ brethren who have a better understanding of this game and a greater familiarity with their homegrown technologies. They will find a captive market not only among big businesses in India, but also several sections of our government who still feel that foreign connections somehow add value to the process, regardless of the professional content of their services. We can then look forward to being ‘local architects’ (read ‘fixers’ and ‘draughtsmen’) to prima donnas and adventurers from Singapore and America looking to capture global markets. This harks back to the colonial days when the first architectural schools were established by the British to produce draughtsmen for the PWD to process designs made by English architects.

This need not necessarily be our future. Lessons can be learnt from the fast-food industry which is now successfully competing with the onslaught of major multinationals by re-inventing themselves. Not by copying their products, but by adapting traditional Indian cuisine to new techniques now available to meet the changing demand. The fight for retail trade is now on and I am sure traditional retailers will succeed because there is no substitute for ‘local knowledge’.

Historically we have survived several invasions and still maintained our Indian identity even while absorbing the cultural mores of the invaders. It is not beyond us to produce an architecture that responds to the real India – an architecture that does not flatter to deceive.

|

|

|

Her life was her message

|

| (By Ranjitha Ashok) |

|

|

In 1978, when Durgabai wrote The Stone that Speaketh, the story of the Andhra Mahila Sabha, covering a period of 57 years from the 1920s to the late 1970s, she said the title reflected the fact that each foundation stone at the Andhra Mahila Sabha told a story and marked yet another step in the progress of an ever-expanding institution.

The question that emerges is: What are the ‘foundation stones’ that have to be in place in order for the Durgabai Deshmukhs of this world to emerge?

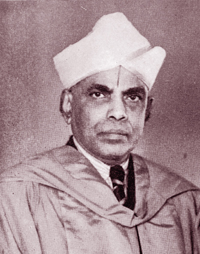

Durgabai Deshmukh |

Durgabai was born on July 15, 1909 in Rajahmundry, Andhra Pradesh. Her parents, B.V.N. Rama Rao and Krishnavenamma, from the very beginning appear to have created an environment which influenced the child Durgabai’s basic character and attitude. Rama Rao introduced his daughter to temples, churches and mosques, building in her a spirit of universal love and respect for all faiths. Parent and child would feed destitute children, instilling in her a sensitivity to the suffering of others. Her mother introduced her to the epics, to their messages of truth, love and dedication.

Her domestic side was not neglected either. Durgabai was an expert cook and homemaker; trained in the art of rangoli, and could play the veena and the harmonium. Her father was a busy social worker and a culturally active person. He would, at a moment’s notice, have to entertain large groups of people, and the young Durgabai would deftly handle chores in the kitchen, playing various roles at the same time. Years later, people would still speak of her cooking skills, especially her upma, dosai and mango pickle.

Even when very young, Durgabai displayed qualities like plainspeaking and courageousness, of being service-minded, of preferring simple living to any kind of ostentation. She became aware of the injustices meted out to women and even in her youth, she opposed child marriages, the dowry system and the ill-treatment of widows. In 1929, when her father passed away, Durgabai prevented her mother from shaving her head. Durgabai herself had been married as a child, fortunately to a very kind and supportive husband. Her husband passed away some years later and Durgabai moved away from domesticity to keep her tryst with Destiny.

She was 12 years old when she heard Gandhiji address a mammoth meeting in Rajahmundry. Mesmerised by his speech, she picked up a Gandhi cap and walked among the crowd, collecting money. She took the brimming cap to Gandhiji, who accepted the girl’s offering and, smiling, asked her to donate her gold bangles too. She responded at once. When she went home, she made a bonfire of all her mill-made clothes and quit her English medium school. From that day forward, she began to wear hand-woven clothes, and learnt to ply the chakra.

In 1922, she gathered the women and children of her neighbourhood, and began running a school in her own home, the Balika Hindi Pathashala, little realising that the nucleus of the Andhra Mahila Sabha and a foundation for adult education was being laid. She was the Principal – she was also a 13-year-old school student herself – teaching mostly adult women. The next year, when the Indian National Congress session was held in Kakinada, Durgabai trained women to work as volunteers, but was deemed too young to be one herself!

She did, however, become a volunteer for the Exhibition and the Hindi Sammelan. One of her duties was to collect tickets at the entrance. It was then that a handsome young man tried to walk in without a ticket. The young Durgabai stopped him, and categorically refused to let him in, forcing him to go and buy a ticket. Konda Venkatappaya, one of the organisers, witnessed this with horror and berated Durgabai – she had stopped no less a personage than Jawaharlal Nehru! “They twisted my ears and asked me whether I knew whom I was turning out.” She did, but insisted that she was “doing her duty”.

And Nehruji agreed with her, commending her fearlessness.

When Durgabai, a forceful and persuasive speaker, was involved in the Salt Satyagraha in 1930 and was arrested, she noticed that political prisoners were not treated equally and protested, saying all satyagrahis ought to place themselves in ‘C’ grade jails, and requested ‘C’ class imprisonment. This dark and difficult period in her life gave her a clear insight into the plight of prisoners. She decided to become a lawyer.

Durgabai knew that lack of education was the root cause of lack of empowerment among women. She decided to educate herself further, for only then could she be of real help. After her release from prison she privately passed the matriculation examination of the Banaras Hindu University, with domestic sciences as one of her electives.

In 1937, her family moved to Madras.

* * *

Durgabai’s house at 14, Dwaraka Street in Mylapore soon became a focal point in the neighbourhood. It was here that the “Little Ladies of Brindavan” was formed, and it was as if the Balika Hindi Pathashala of Kakinada had been given a new lease of life in Madras. In 1939, Durgabai joined the Madras Law College, and also began working for the women and children’s wing of the Chennapuri Andhra Maha Sabha. This soon led to the emergence of the Andhra Mahila Sabha as an independent organisation, focussing, as Durgabai said, “on the social, educational and cultural needs of women.”

She graduated in 1941 and began practising in Madras even while working for the Sabha. Her enrolment as an advocate was delayed because she did not have the money for fees. Legend has it that the Rani of Mirzapur offered her the money. Durgabai had no hesitation in turning it down, preferring a donation for Andhra Mahila Sabha instead, while requesting the Rani to accept the office of the presidentship of the Sabha. Other donations followed.

The first site for the Sabha was gifted by the Rani of Mirzapur. More land was acquired through the generous support of successive Governments. And building after building rose on the land, each housing an activity of the Sabha and becoming an institution in itself.

Years later, she recalled some of the criticisms that had been levelled at her, one of which was that the Andhra Mahila Sabha was a “child of the zamindars”. Her retort was, “Does benevolence, if it comes from zamindars and industrialists, get tainted?”

In time, various institutions, including educational, a full-fledged hospital (which had begun as nursing home), a maternity home, an orthopaedic centre, a milk distribution centre were all added. In time, the Andhra Mahila Sabha spread to other places, like Hyderabad.

And as the Sabha grew in size and stature, so did Durgabai’s role in the national scheme of things.

Durgabai, as a member of the Constituent Assembly, played an active part in drafting the Hindu Code Bill. She became a Member of the Planning Commission in charge of Social Services. Having played a pivotal role in establishing the Central Social Welfare Board, she became its Chairman in 1953. She initiated condensed courses of education, one of the most important programmes ever undertaken by any voluntary organisation. She was a member of the Kasturba National Memorial Trust, and was involved in the training and recruitment of women as grama sevikas.

The year she married C.D. Deshmukh, then Union Finance Minister, she resigned as Member of the Planning Commission much against Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru’s wishes; she felt a husband-and-wife team serving on the same commission would lead to problems. A host of her varied roles followed, but women, education and healthcare remained her focus.

* * *

The passing away of her mother in 1965 was a devastating blow. Durgabai had always maintained that it was her mother, the Sabha’s beloved ‘Ammammagaru’, who provided the human element in the Sabha, with her sympathy, guidance and philosophy. Elements which, for all her resourcefulness, Durgabai felt she could not offer. Durgabai knew that all schemes and projects, well-meant and successful as they are, are ultimately no match for empathy, understanding and the mere act of listening to someone pouring her heart out. This is actually the essence, Durgabai said, of social service.

Durgabai always believed that health and medical services must reach the “doorstep of the rural dweller.” The auxiliary nurse-midwife training programme supported by the Andhra Mahila Sabha proved a tremendous success. Honours followed, including the UNESCO World Peace Medal, and Padma Vibhushan in 1975, which her husband also received the same year in a unique occurrence.

In 1977, when her husband fell ill, Durgabai turned private trauma into yet another learning experience and, using her own money as the kitty, started a unit for cardio-vascular treatment in Hyderabad. It was during this difficult time that she wrote her autobiography titled Chintaman and I and, later, The Stone that Speaketh. She was a prolific writer, with numerous articles and papers on social issues and translations to her credit. She brought out a three-volume encyclopaedia of social work at the request of the Planning Commission.

She felt relief programmes should be institutionalised, and always advocated a close working relationship between voluntary organisations and governments, but did warn that “social service and political ‘partyism’ go ill together.”

Practical and humane, she had a gift of anticipating needs, and provided jobs to hundreds of women, many of whom helped her in building the Andhra Mahila Sabha and in implementing her social welfare projects. She picked up widows, the destitute, and turned them into self-reliant contributors to society. She created in women a desire for knowledge, for education, to work, with 90-year-olds coming up to her and asking to be tutored. “Because I want to read the Ramayana”, they’d answer when asked why. And she had a great gift for finding the right people for the job. She created a workforce filled with committed and dedicated workers, for which mere money was a poor substitute, and never believed in an autonomy bereft of accountability.

She was also blessed with a strong vein of common sense and pragmatism. On the management of the Tourist Hostel in the Sabha (now a three-star hotel), she was shrewd enough to say that such places must be run by “social workers with business acumen” because it is “hospitality plus business”.

On May 9, 1981, Durgabai, with her husband keeping vigil by her side, passed away. Her mortal remains were consigned to flames in the electric crematorium, which was being used for the very first time. Even in death, she proved a pioneer. Eighteen months later, her husband passed away.

Two people from very different backgrounds, but with common goals and aspirations; they had complemented one another perfectly through their life together.

Durgabai always chose struggle, self-denial and sacrifice over softer options in whatever roles she played. And she excelled in all those roles – without the benefit of influence of money, famous family name or dynastic support. She took no short cuts to success. Her philosophy was simple: practise rather than preach.

Her life was her message.

Author’s Note: Based on: Durgabai: Life and Message by Prof. I.V. Chalapati Rao and The Stone that Speaketh by Durgabai Deshmukh.

|

|

|

One extended family is what it used to be |

| (By Shobha Menon) |

|

|

(Continued from last fortnight)

Dr. T.S. Madhurambal |

The Midwifery School at MH started functioning in the middle of the 19th Century and was recognised in 1874. The ‘red jackets’, or ‘vernacular nurses’, or maternity assistants, were trained for 18 months in Tamil. The midwifery training for ANM was given from 1956 and is reported to have continued upto 1971.

The Family Welfare Clinic of the Hospital was started on April 2, 1951 with the help of a social worker deputed from the All India Women’s Organisation. In 1962, staff was posted exclusively for family welfare work and an urban family welfare centre started functioning in 1967.

Care of low birth-weight babies born in the Hospital was organised by the pioneer in Paediatrics, Prof. S.T. Achar and his team, along with Nursing Tutor Sister Crasta in 1962, with 28 beds for pre-term/low birth-weight babies. The mortality rate was as high as 60 per cent at the time. Care was provided by the paediatric team from the sister institution, the Institute of Child Health and Hospital for Children.

By 1976, Dr. Bhaskar Rao and Prof. Balagopal Raju, along with Prof. Tirugnansambandam, addressed the need for neonates born here to be within reach of their mothers. When Prof. F.S. Philips, then Director, created a separate post for Lecturer in Neonatology in 1982, the Unit took its first steps! From then on, the Unit’s neonates were managed within the Hospital round the clock, with 12 nursing staff. Around 1987, neonatal care was further strengthened with the support of the Family Welfare Directorate of Tamil Nadu, leading to an 85 per cent survival rate as against the earlier 30-40 per cent.

Dr. Rathnakumari, the current Chief of Neonatology, is justifiably proud of her excellently equipped Neonatal Unit. “40 per cent of the babies born at MH are in the high risk category, and the MH’s Neonatal Unit can cater to neonates in the best possible standards (with better equipment each year!).”

Dr. Madhurambal, who was the Director during the 150th year celebrations in February 1994, remembers, “We used to start work at 7 a.m., complete rounds by 2 p.m., after a half hour break for lunch, back to classes till 4 p.m., and thereafter some work in the wards. I received my MBBS degree from Sir A.L. Mudaliar. There was no barrier between junior and senior, Chief or Assistant. I remember Dr. Indra Ramamoorthy, then Honorary Chief at MH, offering to be on duty so that I could take a day off!”

Dr. Madhini, who retired as Director in 2005-2006, says, “In the 1960s, we had regular classes at MH for undergraduate and postgraduate students, but now only the final years do. The PGs were compulsorily asked to stay in the Quarters. And we’d just walk down to class in Gifford Hall! It was a time of strict discipline and we imbibed rigorous standards that have served us well. Work was worship and where you came from was considered irrelevant! However, even till the late 1970s, unmarried women were preferred as PG Assistants. The post duty off concept started only in the early 1980s. Till then we all did even 30 hours duty at a stretch. If ‘Theatre’ began at 8 a.m., we were to reach at 7 a.m. By 7.01 a.m., the Dean would be doing what you were supposed to do – filling in the Outpatient Sheet! The then Director, Dr. Bhaskar Rao, was a stickler for discipline. All the PGs conducted entire routine blood tests themselves – Blood group, Rh, sugar, albumin, etc.”

I also met octogenarian and well-known obstetrician, Dr. Kamakshi Kabir, who retired as Acting Director of the Institute of Ob Gyn in 1977. Her eyes still light up as she remembers the excellent teachings by stalwarts like Dr. ALM, Dr. E.V. Kalyani, Dr. Madhavi Amma, and Dr. Thampan’s expertise in clinical studies. “Dr. Krishna Menon was so brilliant that he could present a case in a way that could make you feel the answer was ‘Yes’ and ‘No’! The emphasis then was on clinical methods. We diagnosed and used the test to confirm the diagnosis! And the whole unit was like one extended family,” Dr. Madhini recalls.

The current Director, Dr. Renuka Devi, took over on January 31, 2009. She says, “Our Obstetric Care Intensive Care Unit can be considered the best in India. It has the best equipment, comparable with the finest in the world. We also have well equipped Medical Oncology, Radiotherapy, Endocrinology and Genetics Departments, all under one roof, and seven Operation Theatres. A 24-hour Casualty Department ensures round-the-clock critical care for all incoming patients. Our ICU has referrals from across Tamil Nadu and even Andhra Pradesh. Being a premier hospital in India with the second lowest mortality rate in the entire country, MH has been designated as a Centre of Excellence.”

Dr. Renuka Devi |

However, a senior gynaecologist at the Hospital feels, “Designating the MH as a Tertiary Care Centre could help more research and critical clinical recording of obstetric cases. In spite of the four existing peripheral centres in different parts of the city (in Periyar Nagar, Saidapet, Tondiarpet and Anna Nagar), patients often come here because their mothers and grandmothers came here for their deliveries! Which means a large part of the existing short-staffed team is constantly at work, attending to routine cases most times. There is also an urgent need for social workers and counsellors, and it is rather unfortunate that old vacancies are rarely filled in this sphere.”

A recent Rs. 7 crore grant from the Central Government will, over the next few months, prove beneficial for the thronging patients in need of critical care facilities, but disastrous for the central portion of the old hospital (since the cost of restoring the old building will be more than the cost of rebuilding anew, according to the Public Works Department!). So, the airy corridors of the old central block, with its high ceilings that transport you into a bygone era will soon be replaced. A College of Nursing and Nurses’ Hostel is also slated to come up on the premises of the Lady Lawley’s Nurses Quarters.

On an escorted tour of the hospital campus, through milling crowds and crowded wards, I was amazed by the magnitude of the facilities and the services that continue to be provided by this medical institution whose origins are so steeped in history. And like the ancient mahogany tree that stands tall in the quadrangle outside, comforting anxious patients and their attendants under its cool shady branches, the Maternity Hospital continues to draw generations of women and their newborns to seek its shelter, reiterating its name as one of the finest in India.

‘What are you doing, child?’

I entered the portals of the Maternity Hospital as a IV year medical student in December 1943. My first impression on seeing the beautiful red building was one of awe. That year, the course in Midwifery was mainly theoretical, with lectures by famous teachers like Sir A. Lakshmanaswami Mudaliar. He had already published his textbook of ‘Midwifery’ which was read by medical students all over India.

The final year was most exciting when practical training was given in delivering babies.

A few students were interned in batches for a period of one month. And internment meant real internment, where you had to be always ready when called to deliver a patient. So it was 24-hour duty waiting for the call (a bell!) from the labour room summoning you. Those on duty stayed in the labour room – our heads nodding with sleep in the early hours of the day. When the patient was ready to deliver, we were summoned by the Labour Ward chief sister, Sister Lily Jacob, a strict disciplinarian. Students had to be like soldiers and stand to attention always. I remember once when I had to deliver a case, the face mask I wore (and which I was not used to) rode high up on my face covering my eyes, and I could not see what I was doing. Sister Jacob shouted, “What are you doing, child?” In a frightened tone, I said, “I cannot see.” Sister looked up and started laughing. She pulled the sterile mask down and, lo and behold, it was just in time for a bonny baby to be born, crying its lungs out! I was all smiles and happy… I did not realise at that time that I was going to take up Midwifery as my speciality.

Dr. A. L. Mudaliar |

MH was at that time the premier training centre for Obstetrics and Gynaecology in the country. Students came from all over India for training as PGs. Our teachers were highly respected and loved by us – as undergraduate and postgraduate students. Famous among them were Sir AL and Major Thomas. In the pre-Independence days, most of the professors were British. Some of them taught very well, others were indifferent. Major Thomas was a good teacher, but his experience in surgery was limited. It was his assistant, Dr. E.V. Kalyani, who actually did the major part of the surgery. Later Dr. R.K. Thampan and Dr. M.K. Krishna Menon were excellent teachers in both theory and practice. The other teachers greatly respected were Dr. E.V. Kalyani and Dr. Madhaviamma. There used to be keen competition among the students to get a posting under them!

After passing the final year and doing my house surgeoncy in Medicine, Surgery and Obstetrics & Gynaecology, I had to decide on the speciality I would take up for life. I personally liked Medicine, as I worked as a house surgeon under Col. M. Robert and his Assistant Dr. S.K. Sundram and Dr. K.S. Sanjeevi, who inspired me. At the time there were only one or two women physicians and I was advised by my parents and teachers to opt for Midwifery. MH was the only institution recognised for PG training in this speciality. It was a time when the Gosha Hospital was not recognised for PG training, which was a pity because there was a lot more clinical material there, the medical staff were all women and the patients of the area flocked to the hospital.

Dr. AL was responsible for the excellent collection in the Hospital Museum of specimens of tumours of the female reproductive system and abnormal babies. The Museum as well as the teaching was in the Gifford School – a sacred place for us as students and teachers. The two main operation theatres were named after two brilliant teachers (of the Indian Medical Services), the H Theatre after Hingston and G Theatre after Gifford.

I enjoyed being trained in Ob and Gyn at MH and, later, after further qualifying in London, I joined MH as an Honorary Assistant under Dr. Thampan and later worked with Dr. M.K.K. Menon. It was during my early years as an Assistant that I became well trained both in the practice and teaching of Ob and Gyn.

Later, I became an Honorary Chief of a Unit and enjoyed every moment of my life at MH till I retired in 1978.

- Dr. Indra Ramamoorthi |

(Concluded)

|

|

|

| Savitha Gautam |

|

Meet Lata Mangeshkar and A.R. Rahman

Today, I feature books on two artistes who have had a tremendous influence on Indian film music, past and present. One held the country enthralled with her rich and melodious voice for well over four decades, while the other, an Oscar winner, has captured the imagination of young India with music that’s fresh, peppy and technically brilliant.

Lata Mangeshkar: In Her Own Voice – Nasreen Munni Kabir (Niyogi Books, Rs.1,500)

This coffee table book mostly with black and white photographs, some of them rare, instantly draws your attention. The jacket shows a young Lata looking up at the camera with joy writ large on her face. This picture reflects the general tone of the book.

Nasreen Munni Kabir chronicles the meteoric rise of a young Maharashtrian girl with a golden voice. The whole book is in an interview format and makes for easy reading. Lata’s memories of her father, whom she lost quite early in life, her brief acting stint to bring home some bread, her love for cycling and diamonds, besides her alleged feud with sister Asha Bhonsle, the O.P. Nayyar fracas… there’s enough in these pages to keep readers engrossed.

However, if you are looking for some spicy or juicy stuff, you may be disappointed. For, there’s hardly anything here that will stir a hornet’s nest! But you get nuggets like her favourite films (King and I and Singing in the Rain), her love for anklets (she wears only gold ones!), her first Hillman car (she used to drive, till she rammed into a truck) and her trips abroad.

Here’s the Chennai angle. She counts actor Sivaji Ganesan and his family among her close friends. Remember she visited Kamala, Sivaji’s wife, after the legendary actor passed away? Similarly, she had great regard for fellow Bharat Ratna awardee M.S. Subbulakshmi.

Nasreen, who had made a documentary on Lata in 1991, had quite a bit of research already in place when he started on the book. It was just asking the right questions to the ‘Nightingale of India’. There are personal anecdotes by actors such as Waheeda Rahman, Dilip Kumar and Jaya Bachchan, director Yash Chopra, writers Gulzar and Majrooh Sultanpuri, sisters Asha, Usha and Meena, brother Hridaynath and her nieces and nephews, among others.

If you are hoping to learn a little more about the legendary singer, well, some of you may be disappointed. But there are moments when Lata almost lets down her guard. Nasreen has played it safe. So this is a somewhat sanitised version of Lata’s life. However, it’s an enjoyable read.

* * *

A.R. Rahman: The Musical Storm – Kamini Mathai (Penguin, Rs. 499).

Now, here’s a book about a Chennai boy by a Chennai girl! Kamini Mathai, a journalist with The Times of India, is in awe of her subject with whom she started interacting when she was with The New Indian Express. Though getting the reclusive Rahman to talk about himself proved to be quite a difficult task, as she admits, Kamini has managed to get a brief glimpse of the man and the musician that is Rahman. Incidentally, Rahman has called the book an ‘unauthorised biography.’

|

The early pages of the book are devoted to Rahman’s father R.A. Sekhar, a much-sought-after arranger for Malayalam films. A hard-working musician, Sekhar had dreams of making it big. Sadly, cancer cut his life short when Rahman (Dileep those days) was just nine. The financial situation of the family led 11-year-old Dileep to become a sessions musician for Telugu, Malayalam and Tamil music directors. Jingles followed and, soon, life became a little smoother. But 1992 changed Rahman’s life forever. That was the year Roja was released.

Kamini devotes quite a few pages to draw comparisons between the working style of the young composer with that of giants such as Ilaiyaraja and MSV.

As you turn the pages, you think you are a little closer to Rahman, the person, but at the end you realise that he continues to be an enigma. And that’s what makes the read interesting!

|

|

|

|

|