| (ARCHIVE) Vol. XX No. 1, april 16-30, 2010 |

|

Quick Links

The Gujaratis of Madras: The jewellers’ contribution

An Icelander’s view of 17th C. Tranquebar

A. Madhaviah: A fogotten iconoclast

On the Bookshelves

|

|

Bapalal’s, Mehta Diamonds, N. Gopaldas are some of the Gujarati firms in the jewellery trade in the city today. These firms continue a long association Gujarati jewellers have had with the city and the Madras Presidency. Many of them have left an indelible mark, thanks to their business acumen and the various philanthropic activities they were involved in.

Gopinatha Tawker of T.R. Tawker and Sons.

Surajmal Mehta.

Shriman Jeshinglalbhai of Soorajmal Lalubhai & Co., Madras.

Surajmal’s Diamond House – Esplanade, Madras.

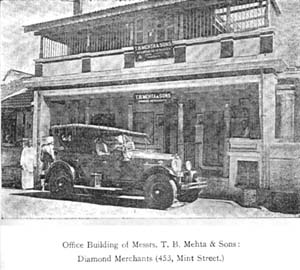

Office Building of T.B. Mehta & Sons – Diamond Merchants (453, Mint Street). |

In this article I take a look at a few prominent Gujarati jewellers of Madras and their contributions to the city. The list is by no means comprehensive and I welcome more information on the subject.

The Tawkers, belonging to the Khedawal community, were one of the earliest Gujarati families in the diamond trade. The earliest mention of a Tawker is found in 1759 with one Nilakanta Tawker being mentioned in the private diary of Ananda Ranga Pillai, the dubash of Francois Dupleix, the Governor of Pondicherry. This Tawker is mentioned as a diamond merchant who helped the French sell for 54,000 pagodas a large consignment of diamonds plundered from an English ship.

The descendants of Nilakanta Tawker flourished as the leading diamond merchants in the late 19th Century and the beginning of the 20th Century. Somerset Playne, in his book Southern India: Its History, People, Commerce and Industrial Resources (1914), mentions a T. Ambasanker Tawker who, he says, “does not have any difficulty in tracing his business to over 200 years.” The business, which was carried out under the name T.R.Tawker and Sons, had a large client base which included zamindars, royalty and leading musicians, prominent amongst them being Bangalore Nagarathnammal. Her will executed in 1949 has one of the later Tawkers signing as a witness. The Tawkers’ showroom on Mount Road, next to where the VGP building now stands, was built in the mid-1890s. Tawkers Gardens, their residence, was where New College later came up.

Along with P.Orr and Sons, the Tawkers represented Madras at the Art Gallery that was put up in Delhi as a part of the Coronation Durbar in 1903.The Official Catalogue speaks of a whole section of the jewellery court occupied by the Tawkers, the entire collection having been valued at a then phenomenal Rs. 60 lakh.

T.R. Tawker & Sons began running into financial difficulties in the first and second decades of the 20th Century. Their financial troubles were caused principally due to the death of Mahboob Ali Pasha, the 6th Nizam of Hyderabad, to whom they had supplied an expensive robe studded with diamonds and from whom payment was awaited when he died in 1911. The promised money never came and the stones were never returned. The Tawkers were declared insolvent in January 1925. The descendants of the Tawkers have moved away from the hereditary business and are now in various professions, such as banking and engineering.

Another prominent Khedawal family business in the diamond trade was that of T.B. Mehta and Sons. In the mid-1600s, two brothers from the family, Kameshwar Mehta and Kunwar Mehta, migrated to Tanjore from Mahuda in Gujarat and began a jewellery brokerage business. Balakrishna Mehta, the founder of the jewellery firm, was born in 1834 to Rajaram Mehta, a descendant of Kameshwar Mehta. He had no formal education but learnt Gujarati from his father (who passed away when Balakrishna Mehta was quite young) and learnt Tamil from a Brahmin pandit in Tanjore. After marrying Bhavani Bai, the sister of Ranganatha Kripashankar Tawker (of T.R. Tawker and Sons), he shifted to Madras in 1871-72 to expand his diamond business.

Two of Balakrishna Mehta’s sons, Subbaroya Mehta and Neelakanta Mehta (born in 1866 and 1868, respectively), continued the diamond business after the death of Balakrishna Mehta in 1899. Operating from 453 Mint Street, Madras, the business had amongst its valuable customers the Maharajah of Mysore, the Rajah of Venkatagiri and the Rajah of Kalahasti. Neelakanta Mehta passed away in 1910. A street in T.Nagar commemorates his name today. The business, which was later carried on by his son T. Ramanatha Mehta (who entered it in 1911), wound up sometime in the middle of the 20th Century. Sivasankara Mehta, the son of Ramanatha Mehta, served for a brief while as the Sheriff of Madras in the 1960s and was also a member of the Madras Legislative Council.

Surajmal Lallubhai was a well-known name in the early 20th Century in the diamond trade. Originally from Palanpur in Gujarat, he came to Bombay when he was 17, driven by an urge to make it big in business. He opened a diamond jewellery shop in 1895, when he was only 20. He was helped by his family members, Keshavlalbhai, Manilalbhai, Hiralalbhai. He also appointed an agent at Antwerp, Belgium, to source diamonds at an affordable rate. Business flourished and his customers included Rajahs, Nawabs and Zamindars.

The firm soon established branches in Rangoon, Calcutta (under the name Thakurlal Hiralal), Madras and Trichy. The Madras branch, started in 1916, was looked after by Jaisinghlalbhai, the son of one of the brothers of Surajmal Lallubhai. The company later got involved in the gramophone records business with the setting up of a company in Madras in December 1933 called Musical Products Limited with a capital of Rs.50,000. The Broadcast label was taken on licence from Vocalion of England. Recordings were made in Bombay, Madras, Calcutta and Colombo. To establish the connection with the diamond trade, the Broadcast logo featured a diamond and the record labels came in several bright colours. Broadcast boasted of a longer playing duration as compared to other records of the time. Prominent artistes to have recorded included M.S. Subbulakshmi and her mother, Mysore T. Chowdiah and Rajamanickam Pillai. However, this venture did not last long due to dull sales and the company was wound up in 1937. Surajmal’s continued in the diamond trade for long after.

The Veecumsees were another group that originally started out in the jewellery trade. They are, however, remembered more for developing the first multiplex cinema hall in the country, the Safire. The other theatres in the same complex were the Blue Diamond and Emerald, all the theatres being named after components of their principal business. Their concept of a viewer watching a movie throughout the day by buying just a single ticket was an innovation in the Madras of the day. Today, the place where this multiplex stood is seeing new highrise development.

Bapalal’s, who are in trade even today, was founded in 1910 by Bapalal Mehta, a merchant from Palanpur in Gujarat. Their business was initially carried on from 216 China Bazaar Road. Mehta Jewellery, started in the early 1990s, is an offshoot of this firm. This firm was started by Surendra Mehta who came to Madras in 1941 initially to join his uncle Bapalal Mehta in the diamond trade.

N. Gopaldas and Co., though a recent entrant to the city, is no stranger to the Madras Presidency, their firm having been established in 1929 in Trichy, where it is headquartered. Besides Trichy and Madras, the group has also a prominent presence in Kumbakonam.

Another prominent firm was that of T.R. Joshi and Sons, operating from 38 Ekambareshwara Agraharam, Park Town. The business, being carried on by the descendants of the founders, is currently celebrating its centenary year.

The Tawkers were renowned for their philanthropy. Two women from the family (though not directly related to the diamond traders), Ramkaur Bai and Ratna Bai, returned from a pilgrimage to Varanasi with two huge Shiva lingams. One was installed in the Kashi Viswanatha Temple in Ayanavaram, to which shrine they had endowed lands, and the other was installed at Motta Uttara, the community hall of the Dakshin Gujarati Khedawal Samaj on Mint Street. A trust called the Tawkers Charities was also established and the Tawker Chattiram in Ayanavaram, a students’ hostel, still functions.

On his death bed, Nilakanta Mehta donated a sum of Rs.30,000 to his alma mater, Pachaiyappa’s College, for the building of a hostel for students, the central block of which was named after him. He donated a further sum of Rs. 3000 as an endowment for Gujarati students of the college. The then Governor of Madras, Lord Pentland, recognised his charitable acts with a certificate of honour.

Tawker’s and its neighbour

|

In the picture on left, of Mount Road ‘shot’ from Narasinghapuram Street, is the handsome Henry Irwin Indo-Saracenic (with clock) of T.R. Tawker and Sons, leading jewellers at the turn of the 20th Century and a family whose philanthropy was legendary. The Tawkers bought the property in 1893 and T. Manavala Chetty was the contractor who raised Tawker Building not long after that. The magnificent showroom was sold by the Gujarati family to the Rajah of Venkatagiri in 1926 and, subsequently, it passed into the hands of Kasturi Estates in 1931. The South India Cooperative Insurance bought the building in 1948 and, on the nationalisation of life insurance in 1956, it became Life Insurance Corporation property. Its ground floor was occupied by the Indian Airlines’ passenger office from 1953, when the airline was founded. Soon after the airline moved into its new Marshall’s Road offices in 1979, the SICI Building was pulled down and a new building built by LIC. The picture was taken shortly before the building fell to the wreckers’ hammers in 1980. LIC built by 1988 a replacement for Irwin’s palatial structure, but nothing in the new construction reflected the old, palatial building.

Partly visible building in the Vintage Vignettes picture on left is the Tawker Building. Next to it was Whiteway, Laidlaw’s. Whiteway’s, Furnishers and General Drapers, had shops in other Indian cities as well as in several other parts of Britain’s Asian empire, but quit India with the British. The Swadesamitran, the pioneering Tamil daily, bought what its proprietor, C.R. Srinivasan, named Victory House. When Swadesamitran fell on sad times in the face of competition from upstart Tamil dailies speaking the Tamil of the street, Victory House was sold in 1975 to the VGP group, whose founder V.G. Panneerdas not only had a rags to riches career but built it by pioneering hire purchase business of consumer durables for the middle class homes of Tamil Nadu.

Back to top

|

|

|

|

|

I was pleasantly surprised to read* that an Icelander, Jon Olaffson, had come to Tarangampadi (Tranquebar) and Thanjavur as a member of the first Royal Danish expedition in the early 17th Century.

Part 1 of the book is about Olaffson’s birth and youth in remote northwestern Iceland, his sea trip to and stay in England in 1615, and his life as a gunner’s mate in the service of Christian IV, the King of Denmark. In Part 2 he details his voyage to India in 1622, his life as a member of the Danish garrison in Tranquebar (the Dansborg fort), his return to Iceland in 1624-1625, and his life there till his death at the age of 85 in 1679. Bertha Philpotts, the editor of the Jon Olaffson volumes, cautions that the book was written much later in his life by reconstructing information from memory. His note on Page 1, Part 1, says: “Related ... as he can best recall it now in his old age in 1661.”

He arrived in Tranquebar aboard the Christinashavn via Ceylon. He describes Dansborg fort as one with handsome walls, well furnished with bastions at each corner, and turrets on each bastion with a gilded vane; in the middle of the fort stood the church, previously occupied by a Portuguese abbot, which seems to have serviced the religious needs of all Christians. The fort was maintained by Erick the Smith, although the hard work was done by native masons who, according to Olaffson, were more swift and skilful than those of Europe. He describes the defences of the fort and the quality and quantity of rations the soldiers received. His notes on the goats (adu) and their colour variations are impressive. He refers to fabric materials: cotton, silk, and mohair. Refering to mohair, Olaffson considers it velvet and indicates it to be of tree origin which, in fact, should have been a form of silk possibly derived from a non-mulberry source. He is confused in his description of the banana and coconut palms. In the context of coconut palm, he mentions the extraction of oil using an ox-pulled cekku, describing it in many words. He mentions that Indians consume boiled meat, splendidly spiced with saffron broth (curry); they eat meat of goat origin, fresh and oil-fried. He elaborately describes the practice of cow-worship and the chewing of vetrilai by Raghunata Nayak (mentioned as Nica de Regnate), the King of Tanjore. He describes his court rooms and the ‘concubine’ hall in the palace, which is furnished with gilded pillars and windows of crystal glass (incidence of ‘crystal’ glass windows is disputed). He makes a quick reference to the committing of sati. He describes the Hindu temple in Tarangampadi (the ancient Siva temple about 200 m from the fort?), various Gods, and traditional street processions. The descriptions are highly distorted and Phillpott challenges many details.

His descriptions then move on to Tanjore. The following remarks of his are not only curious, but also evoke our respect: “We often entered them (sic temples in Tanjore) when no one was by, but I preferred to stand guard outside, and forbade the others to play any evil tricks. Sometimes they extinguished the lights (sic oil lamps), but I threatened them with severe penalties if they broke the gods or showed them dishonour, which, however, I often had much ado to prevent.” He then describes the street drama (theru-k-koothu) performed at night and the jugglery he witnessed, a game played with two awls of different lengths, the shorter one being hit with the longer one (kitti-pullu?), and another gory game of piercing a hole in the upper arm and pulling a hemp cord through the hole. He talks of the colourful arrival of the chief Hindu priest on a caparisoned elephant by crossing the river confluence – possibly in the context of Thai poosam – his departure to Trichlagour (Tiru-k-kadayur?), and the ‘holy’ plants used in Hindu traditions (kusa [darbai] and tulasi), although the details included are messy.

He later refers to laws that governed the town and people and the cruel punishments. He lists a few Tamil words but, significantly, remarks that the language spoken in Tarangampadi was highly corrupted with Portuguese.

He describes the rice sowing that occurred in April and September and speaks of butter extracted by churning milk. Referring to the butter used for frying meat and fish, he indicates that it was red(?); he also indicates use of clarified butter (nei, which could be red because of burning of the milk-proteins).

He gives a confused but picturesque description of the palmyra palm stating that the locals used the leaves as ‘paper’ (olai) and made ‘books’ (suvadi).

He speaks eloquently of ironsmithy practised in Tranquebar and remarks that the smiths were as efficient as those in North Africa. The tongs, anvil, hammer, and bellows used by the Tranquebar ironsmiths are explained and he is astonished with the rib-less bellows. He refers to the boat-building industry of the time: large ships (Portuguese: navis), smacks (siampans, sampans), boats zelings (celinga, salandi), rowed by 10-12 men, and cadmeda (kattumaram). He describes the great turtle of the Indian Ocean (Chelone mydas), which was caught by a fisherman and which Olaffson bought to keep as a pet and found it could pull a human adult. He remarks: “Many ignorant persons think it very miraculous that a creature no larger than this should have so much strength. O how surpassing are the works of God and wonderful and awful to the understanding of men!”

Although the details supplied are either distorted or exaggerated and, sometimes, even incorrect, what is remarkable is his resolute enthusiasm in recording the details of Tranquebar and Tanjore as he saw them. Some parts of his notes are convincing; but Philpott, the editor, has provided correct notations by commenting on matters which are either erroneous or exaggerated. But with Iceland separated from Denmark by a distance of 1800 km and from a landmass close to the Arctic, what is noteworthy is that here was a person who adventured into a tropical land of high humidity thousands of miles away and who lived there for a couple of years, and recorded his observations as faithfully as possible!

Foot Note:- * Phillpotts, Bertha (1923) The life of the Icelander Jon Olaffson: traveller to India (translated from the Icelandic edition by Sigfus Blondal), 2 parts. Published by the Hakluyt Society, London, England. Part 1, 238 pages; Part 2, 290 pages. [A reprint of the book (1967, both parts) by Kraus Reprint Limited (Nendeln, Liechtenstein) is available.]

Back to top

|

|

|

|

|

One historic building on Edward Elliot’s Road came downquietly and unnoticed two years ago. Perunkulam* House, residence of

A. Madhaviah (1872–1925), was a meeting point for Tamil literary giants of the day such as Mu. Ragavaiyangar, U.V. Swaminatha Iyer, Subramaniya Bharatiyar and Kathirsesa Chettiar. Many pioneering works written by Madhaviah in English and Tamil came out of a small press that functioned here.

Madhaviah earned his literary credentials even as a student in Madras Christian College with the poems he published in the college journal, a prestigious publication in those decades. After his postgraduate degree, he entered government service, worked in the Salt Department, but took voluntary retirement at fifty to devote himself wholly to literary pursuits.

A pioneer of modern Tamil prose and author of the second published Tamil novel in history, Padmavathi Charithram (1898), he edited and published two magazines, Panchamirtham and Thamizhar Nesan, from his house.

A prolific writer, active from 1892 to 1924, he has left behind an impressive body of work that includes poetry, fiction and essays in both Tamil and English. His writings were laced with humour and sarcasm, qualities that were to be a notable feature of his equally famous son M. Krishnan.

Madhaviah was known for his iconoclastic ideas, particularly on the position of women in society and his strong opposition to orthodoxy. He took a strident stand against caste oppression. These ideas manifested in his writings, particularly in the novel Muthu Meenakshi. He wrote at least 24 short stories in The Hindu. He used his pen courageously to support the struggle for justice and peace.

All his eight children shone in different fields. Ananthanarayanan entered the Indian Civil Service and M. Krishnan made a name as a naturalist and a photographer. During the many evenings I spent with Krishnan in Perunkulam House, I heard him talk admiringly of his father.

At the height of anglophilism in colonial India, Madhaviah believed that Tamil should be the medium of instruction if the downtrodden were to be helped. In October 1925 he was speaking in the Madras University Senate on this subject, when he just slumped in his seat and died.

Because of his iconoclastic views he went unsung and unhonoured in his lifetime. Dr. Raj Gowthaman of Pondicherry University studied the Tamil works of Madhaviah for his Ph.D. and published Madhaviahvin Samuga Novelkal: Oru aazhnilai paarvai (1991). One of Madhaviah’s well known novels is Clarinda, based on the story of a young Brahmin widow, who lived with a British officer and converted to Christianity. The church Clarinda built in Palayamkottai, known among the locals as ‘Pappathi Kovil’, is still under worship.

(Many works of A. Madhaviah, including the first editions of Kusigar Kutti Kathaikal (Tamil) and The Story of Ramayana (English) are preserved in the Roja Muthiah Research Library, Chennai.)

Foot Note:- * Perunkulam, the native village of Madhaviah, is near Tirunelveli.

Back to top

|

|

|

| (By Savitha Gautam) |

|

Witness to four murders

Songs of Blood and Sword

Fatima Bhutto (Penguin, Rs. 699)

There’s nothing more tragic than losing a parent in the most unfortunate and unnatural of circumstances. But when a young girl is witness to four murders of her close family, well, you can imagine the trauma.

That’s the traumatic life of Fatima Bhutto, granddaughter of slain Pakistani leader Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, daughter of murdered Murtaza Bhutto and the niece of Shahnawaz and Benazir, both killed. The book not only traces the history of one of Pakistan’s most prominent political families, but also is a mirror to the tumultuous events of the nation itself. It is also Fatima’s search for answers as to why her father Murtaza was killed. Candid, heartrending and powerful images are thrown up as Fatima makes trips to various cities and meets people who had interacted with her father… college friends, colleagues and extended family members. Her mother Ghinwa plays a pivotal role all along.

Moving at times and hard-hitting at others, Fatima’s bitterness about, and estrangement with, aunt Benazir consumes quite a few pages. And you actually feel sorry for the young girl. Here was a girl who just wanted to have a happy life, be with her parents and family, and lead a normal life. But that was never to be…

Like William Dalrymple says, “If there is anyone born to write this story, it is Fatima Bhutto.”

* * *

The original family car

The Maruti Story: How A Public Sector Put India On Wheels

R.C. Bhargava and Seetha (Harper India, Rs. 499)

Long before the Tatas invented the Nano, there was Maruti 800... the original family car. And who better to narrate the birth and journey of India’s first indigenous car than Bhargava, who was at the helm of the company and is currently its chairman.

The Maruti, when it was launched in 1983, truly revolutionised the industry and put the country on wheels. It took a little over two years to find the right partner, finalise the legal documentation, get governmental approval to these agreements as well as to the investment proposals, build a factory, develop a supplier base to meet localisation regulations, create a sales and service network, and develop and launch a people’s car. All this was completed and Maruti went on to sell 100,000 cars a year, in a sector where Indian expertise was limited.

26 years later, the Company, now free of government controls and facing competition from the world’s major manufacturers who have entered the Indian market, still leads the way. Yes, the 800 may be being phased out… but it is still a brand which stands on its own.

Co-authored by senior journalist and author Seetha, Bhargava’s book tracks an incredible story of grit, management skill and entrepreneurship.

* * *

His craving for land

The Double Life Of Ramalinga Raju

Kingshuk Nag (Harper Collins Business, Rs. 250)

Nothing sells like a scandal. Especially so when the name involved is Ramalinga Raju. Nag writes about the dramatic rise and fall of an IT czar who ran a $ 2 billion company one day and was taken prisoner the next! Ramalinga Raju, the promoter of the blue chip software company Satyam, created a profitable company in a short period of time, only to leave it penniless. At the heart of the scandal lay the IT baron’s craving for land (his family’s traditional business). To satisfy it, Raju pawned his shareholding in Satyam as well as in his real estate company, Maytas Infra and, allegedly, siphoned off funds from both companies.

In a cover-up, Raju allegedly fudged Satyam’s books to inflate its revenues and profits, so as to increase the value of its shares. Raju was able to do this for eight years – until the recession hit in 2008 – and the bubble blew in his face. But how did Raju build his empires and amass so much wealth? How could he hoodwink the law, the shareholders and his employees for so long? This unputdownable fly-on-the-wall narrative by Nag, resident editor of the Hyderabad edition of The Times of India, captures the drama of Raju’s life.

Back to top

|

|

|

|

|