| (ARCHIVE) Vol. XX No. 16, December 1-15, 2010 |

|

Quick Links

Sullivan of the Nilgiris

On the trekkers' trail to Nagalapuram

The man who helped restore the Big Temple

On the Bookshelves

|

|

John Sullivan, the Collector of Coimbatore from 1815 to 1830,

who discovered Ootacamund (now wrongly called Udhagamandalam) and established India’s first hill station there, contributed greatly to the welfare of the district and its native people. His legacy continues to benefit the district and its people to this day.

The ‘Save Nilgiris’ campaign launched in the mid-1980s was inspired by Sullivan and his undying love for the Nilgiri hills.

Sullivan came to India at the age of 16 and retired from the service of the East India Company in 1841. His obituary says, “Mr. Sullivan may be said to have continued without a break the energetic and perpetual protest of Sir Thomas Munro’s later years against the East India Company’s system of absorbing and degrading the princes and aristocracy of India, and reducing the whole native population to one dead level of pauperism and serfdom under the Company’s servants. This may be said to have been the entire business of Mr. Sullivan’s life since the period of his retirement from active service.”

Before leaving the Nilgiris and India, Sullivan wrote to a Rev. Metz saying if he could do as he wished he should like to spend his old age in Melur in the Nilgiris. But that was not to be. He died in 1855 in London after a second marriage to Frances Sullivan who brought up his seven remaining children. Where he spent his last days and where he was buried remained a mystery to Sullivan watchers like me till 2000 when I was lucky to trace, through the Internet, his grave to St. Laurence Church in Upton-cum-Chalvey, Slough, London. Thanks to the British Council I could personally visit the Church and pay my respects on behalf of the people of the Nilgiris.

Why was Sullivan not buried in his family vault? It appears Sullivan was an illegitimate child, meaning he was conceived before the marriage formally took place. But he did remain a worthy son of a worthy father, John Sullivan Senior, who was himself a great friend of India. Towards the end of his career, Sullivan did reveal his links to his family. He named his last house in Ooty Richings Lodge, after the house he was born in London, near Iver, Buckinghamshire. He also named the road Richings Road and the one above it Hobart’s Road after his grandfather, Lord Hobart.

In later years Sullivan’s son Henry Edward Sullivan also served in the Madras Civil Service, the third generation to do so, and rendered commendable service during the famine of 1870s.

The Nilgiri Documentation Centre, inspired by Sullivan and the legacy he left behind in the Nilgiris, focusses, among other things, on documenting his life.

Back to top

|

|

|

|

|

Recording the scenery in the “three northern taluqs of Saidapet, Ponneri or Tiruvallur” in The Chingleput, late Madras district, a manual compiled under the orders of the Madras Government, Charles Stewart Crole of the Madras Civil Service, in 1879, adds an exception. “In the extreme north of the latter [Tiruvallur] the Nagalapuram Hills, and the ridge, whose highest peak is the well-known Kambakkam Drug, contribute a little mountain scenery.”

Past the Tamil Nadu border, there’s Nagalapuram, a tiny village bearing the same name as the hills. Here, there is a temple dedicated to Lord Vishnu which, it is claimed, was built by the Vijayanagara King Krishna Devaraya. Ramagiri, Pichattoor, and Surutapalli are some of the other villages in its vicinity; Surutapalli has an ancient temple too; this “houses the only Sayana Sivan called Pallikondeswarar.”

Frolicking at the third pool. |

One recent sunny Sunday morning, a group of 37 trekkers, men, women and children, descended on Arai, a tiny hamlet in the foothills of Nagalapuram hills. Arai is now in the Chittoor District (AP) and is close to a check-dam that separates the village from the hills. A clinic, run by a private trust, where we parked our cars, marked the starting point for the day-long trek organised and led by volunteers from the Chennai Trekking Club [CTC].

That this trek was announced as ‘easy’ by the CTC could have been the reason for the sizeable turnout that included three school students, including a boy less than 10, accompanying his father.

Crossing the check-dam, we entered the dry sclerophyll woods, after crossing a dry river-bed, full of round and polished pebbles. The first encounter with a stream was welcome, because the trekkers could cool their feet and fill their bottles with the sweet water which also made them realise how deprived they were of nature’s bounty in their homes back in Madras that is Chennai. After a short halt, the group proceeded towards the first pool, Pool 1.

In The Silviculture of Indian Trees (Volume I) (1921), R. S. Troup, Indian Forest Service, records that red sanders (Pterocarpus santalinus; (T): çen-çandana-maram) “has a very restricted natural range … found chiefly in the Cuddapah district, … with an outlier in the Kambakkam and the Nagalapuram hills of Chingleput.” Throughout the entire trek, red sanders was the dominant flora.

Without much difficulty, Pool 1 was reached and it was time to rest a while, to enjoy the not-so-chill waters, and also have a light breakfast that had been distributed to trekkers at the starting point along with instructions not to litter the surroundings and to remain close to the group. Thanks to a few trekkers who had brought thermorexin mats, some of us non-swimmers were able to enjoy the waters. A dog accompanied the group from the start to the first pool, leaving many wondering what happened to her beyond that point.

A short distance from Pool 1, we reached Pool 2 which many preferred to call ‘crystal clear pool’. True to that description, its shallow waters were crystal clear.

While some decided to halt at Pool 2, the rest trekked on to Pool 3, which was quite a distance away. The trekking path to the third pool was manageable, but trying at times. Pool 3, much larger and deeper than the other two, was surrounded on all sides by a rocky outcrop reaching 6-10 m in height. After much revelry at the third pool, the group began the return trek to Arai. Given the wooded nature of the trekking path, many realised it would not take much time before it would get dark and, so, increased their pace. Stopping at the last stream for everyone to regroup, we reached the starting point a few minutes after sunset.

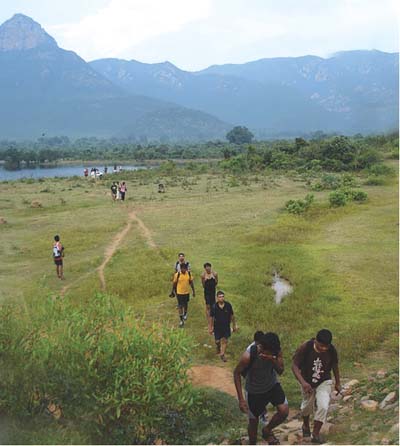

Returning from the hills. |

Old hands in the trekking group made sure all the trekkers returned safely to the starting point. They had also allayed out fears about snakes. True to their word, we spotted none.

In 1971, a few line drawings, depicting 15 figures in white crude thick lines, were reported from the caves at Kambakkam by A.V.N. Sarma, who stated that “these drawings are considered the work of Yenadies, a primitive people who have occasionally been occupying these caves and the nearby area.” However, we did not cross these caves on our trekking route.

NOTE: Nagalapuram is a 3-hour drive from Koyambedu and is well connected with bitumen-topped roads, except for occasional humps and bumps. But beware: There’s another Nagalapuram in Ramanathapuram District.

Back to top

|

|

|

|

|

By education, a botanist; by profession, an archaeologist! Simply listing the number of research papers and books on archaeology published by K.R. Srinivasan would fill many a page, leave alone his contribution to various other facets of archaeology and art history.

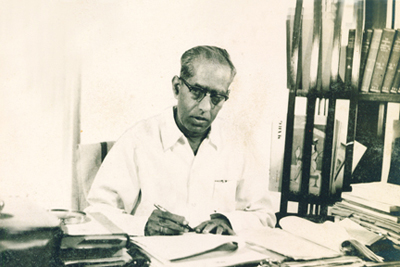

K.R. Srinivasan |

This scholar of great distinction, who contributed to the world of archaeology in various capacities for more than fifty years, was born on July 31, 1910 in Trichinopoly. After obtaining his M.A. degree in Botany from Presidency College, Madras, Srinivasan, by a strange quirk of fate, entered the field of archaeology when he joined as his collaborator his scholar-brother, K.R. Venkataraman, who was directing archaeological studies in Pudukottai State. He worked as Curator, Archaeologist and Epigraphist in the State Museum, Pudukottai, from 1936 to 1946. His training in field archaeology in 1944 came from no less a person than K.N. Dikshit, who was then Director General of Archaeology. He also played an important role in studying the artifacts discovered in the excavations at the famous Roman trade site of Arikamedu (near Pondicherry) by Sir Mortimer Wheeler who, as Director General of Archaeology, spotted his talent and picked him for the post of Assistant Superintending Archaeologist of the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) in 1946.

KRS, as he was affectionately called, was the Superintending Archaeologist of the South-Eastern, Central and Southern Circles and also headed the Temple Survey Project (Southern Region). He finally became the Deputy Director General of Archaeology in 1963 and served in the post till 1968. Many years later, when Wheeler visited India, he was delighted to see his student in one of the highest posts of the ASI. Srinivasan also worked with K.A. Nilakanta Sastri, the doyen among historians of South India, in compiling information for a revised edition of the latter’s monumental work, The Colas.

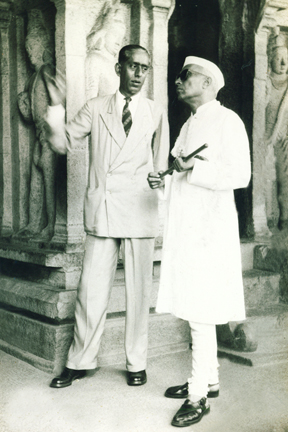

K.R. Srinivasan shows Prime Minister Nehru around Mahabalipuram. |

A frequent visitor to numerous monuments in remote parts of Tamil Nadu and elsewhere, KRS was an expert in conserving ancient structures and protected many of them from decay and disintegration. Because of his expertise in this field, he was sent to Indonesia to prepare a technical report on the preservation of Borobudur. KRS’ background in botany helped him study the problem of moss and lichen on monuments and the results of this were published as a research paper, Vegetation on Monuments.

In a recent lecture-demonstration, noted scholar-dancer Dr. Padma Subrahmaniam pointed out that the 11th Century karana sculptures of the Brihadisvara temple in Thanjavur were discovered in 1956 when an employee of the ASI, while cleaning the temple, discovered a passage in the first tier of the vimana. He reported the matter to KRS, then Superintending Archaeologist of the ASI (Southern Circle), who opened the passage and, after a month of cleaning, found the outstandingly well carved sculptures of the dancing Siva inside. He reported this to the Joint Director General of the ASI, the great scholar T.N. Ramachandran, who identified these as karana sculptures. M.N. Deshpande, an eminent archaeologist who worked with KRS, writes, “The Brihadisvara temple in Thanjavur owes much to his imaginative conservation work. At one time, this monument was full of heaps of debris, growth of vegetation and encroachments. He won the goodwill and cooperation of the trustees and transformed the monument into what it is today. It was during his tenure that chemical conservation of the Chola paintings in this temple was initiated.”

Among the scores of books and articles authored by KRS, Temples of South India, Cave-temples of the Pallavas and Dharmaraja Ratha and Its Sculptures-Mahabalipuram are the best-known. He contributed many a chapter on the temple architecture of various South Indian dynasties to the Encyclopedia of Indian Temple Architecture, published by the American Institute of Indian Studies. His experience in field archaeology and his scholarship in Sanskrit are reflected in his articles which range from a study of megalithic burials to one on an abstruse 10th Century philosophical text, Samkshepa Sariraka. His expertise in Tamil was revealed during the Arikamedu excavations, where he corroborated the archaeological finds in the Roman trade centre with not only references found in the Tamil Sangam works but also from his in-depth study of epigraphy.

KRS taught at various academic institutions of repute, like the Karnatak University in Dharwar, the Tamil Nadu Government School of Arts and Sculpture at Mamallapuram, and the Department of Ancient History and Archaeology, University of Madras. He trained many archaeologists, one of the foremost of them being Prof. K.V.Raman, who retired as the Head of the Department of Ancient History and Archaeology, University of Madras. KRS passed away on November 30, 1992.

The birth centenary year of K.R. Srinivasan incidentally coincides with the millennium year of the construction of the Thanjavur temple. Is it not sad that the landmark date of such an outstanding archaeologist has gone virtually unnoticed in the din of the celebration of the monument he helped painstakingly restore?

Back to top

|

|

|

|

| (By Savitha Gautam) |

|

• On life & spirituality

• A 'what if' tragedy

• Nano idea, macro jolt

Manasarovar – Asokamitran (Penguin, Rs. 225)

This work of the prolific writer has been translated by N. Kalyana Raman. The tale of Satyan Kumar and Gopalan, who have opposing views on life and spirituality but seek the same goal, has not only the characteristic multi-layered perspectives but also the twists and turns that you expect of Asokamitran.

The protagonists seek faith and inner peace and that leads them to Manasarovar. As the translator writes, “…the lake becomes a metaphor for … spiritual attainment. … The novel’s epiphany is inward and metaphorical.”

The novel may be set in the film industry, may be full of references to Indian mythology, but they add new dimensions and complex layers to the story. If you have enjoyed Asokamitran’s earlier works or happen to be a fan of his writing, go ahead and pick up the book.

Small Wonder: The Making of the Nano – Philip Chacko, Christabelle Noronha and Sujata Agarwal (Westland Books, Rs. 295)

Attending business meetings continuously can be tiresome, but it does give rise to some sparkling ideas. It was at one such meeting that Ratan Tata got the first idea of what “would become the car that jolted the automobile world.”

The Nano is Ratan Tata’s dream come true. How this dream was brought to fruition despite several hurdles is what the three co-writers bring out painstakingly in this slim volume. Colour photographs of the prototype and much else add gloss.

In the succinct words of Ravi Kant, vice-chairman, Tata Motors, in his foreword, “The Nano is an automobile with the promise and the potential to change the existing paradigm of the automotive industry not just in India but worldwide. …” The Nano is indigenous India at its best once again. Here’s a product which represents great leadership, splendid team effort, high technology and, most important, it is affordable to the common man. And that in itself makes the Nano story special.

Dara Shukoh: A Play In Verse – Gopal Gandhi (Tranquebar, Rs. 250)

Even after 400 and odd years, the Mughals still fascinate. Anything remote connected with the royal clan which shaped the destiny and future of this nation has plenty of star quality.

In that context, Gopal Gandhi’s thought-provoking play is worth reading. As playwright Girish Karnad says in the blurb, the play “is not just about another historical figure but … a statement of the author’s own philosophy…”

What would have happened if Dara Shukoh and not Aurangazeb had succeeded Shah Jahan? Would it have stopped colonial conquest? Would it have avoided Partition? Well, that’s the premise on which Gandhi bases his poetic tale. The verse form, similar to Vikram Seth’s Golden Gate, has its own charm and makes reading a pleasure.

Riveting, moving and charming, the tragedy of Dara Shukoh finds relevance in modern India. Actor Nazeeruddin Shah writes, “If only history had been taught to us thus in school!” How true!

Back to top

|

|

|

|

|