|

Today, the battlefield at Vandavasi shows no sign of the bloody events of January 22, 1760. Where footsoldiers and cavalry once shot and hacked each other, where cannons smoked and roared and wreaked havoc, there are now fields of rice, mustard-seed and sugarcane. And that’s as it should be.

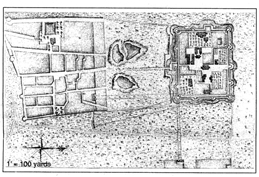

An old plan of Wandiwash Fort. |

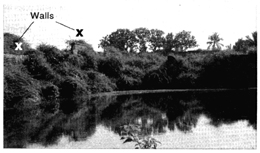

But there are still traces of the fort of Vandavasi in the town itself. Where sentinels once watched for signs of enemy attack, there are now houses, shops, a mosque, a temple and a church beside the remains of the city walls. That, too, is as it should be.

The moat is also still to be seen, although the crocodiles that local lore says once helped guard the fort have vanished. There is also a small tunnel, blocked by large blocks of stone, that the locals say is large enough to take a man on horseback and, at times when the enemy was about to breach the walls, was used by the inhabitants to flee to Gingee, almost 18 miles away. More likely, the tunnel was a simple sally-port or perhaps an escape route to the moat, but the story has a pleasant ring to it.

There are forts like Vandavasi scattered all over the South, some more intact than others.

What’s left of the Wandiwash Fort's wall today. |

The Third War of the Carnatic was in reality part of a wider struggle between the old European rivals – the Seven Years War – at the end of which the French had lost their possessions in Canada, their claims in Europe, and their last chance of extensive colonial territory in India.

So, why was the Battle of Vandavasi so decisive?

One surprising feature of these early struggles was that so few European soldiers were involved. We are talking only of a few thousand men at most on either side. One result of this was that both powers chased each other about the Carnatic without the numerical strength to hold strongholds and at the same time meet the enemy in battle. In the end, they resorted to recruiting the assistance of native princes, even if this meant becoming involved in local feuds and rival claims to thrones. Yet, strangely enough, Vandavasi was the only battle in this war, after the initial cannonade, to have been fought by European forces alone with no Indian involvement: the allies on either side stood and watched as the French and British tried to kill and maim each other.

The sequence of events that led to the battle was not unusual. The British had earlier in the month taken the fort and the French were then in the process of trying to take it back. The British had to watch that the French didn’t sneak behind their backs and once again attack Madras, and the French, for their part, had to keep an eye on their main stronghold of Pondicherry. But the situation had changed elsewhere.

Three years earlier, at Plassey, Clive had ensured Company supremacy in Bengal. Likewise, north of the Carnatic, following the battle of Masulipatnam, British forces were in total control of what is now Andhra Pradesh. The French fleet was in Mauritius and the British fleet had mastery of the Coromandel coast. As a bonus, the French commander, Lally (of Irish-Catholic descent and fiercely anti-British), against the advice of his able subordinate, Bussy, had withdrawn the bulk of his forces from the Deccan in order to launch a massive attack on Madras.

Lally’s siege of Madras failed due to dwindling supplies and the arrival of the British fleet, and he had to withdraw his ragged and underfed forces.

It was at this point that he realised his dilemma; only Gingee, Pondicherry, Karaikal and one or two other isolated strongholds remained in French hands; Vandavasi had recently been taken by the British. There were now only a few French-occupied islands in a British-ruled sea. There was no hope of any reinforcements or extra supplies. In desperation, Lally decided to recapture Vandavasi.

He reckoned without taking into account the skill of the then recently-appointed British commander in the Carnatic, Col. Eyre Coote, who chased after Lally and the French army with the result that on that fateful January day, the British were in the Fort of Vandavasi, the French were camped in the plains nearby giving siege, and the main British forces were on the advance.

Eyre Coote’s plan was to force the French to choose either to divide their forces by maintaining the siege on the one hand and meeting the advancing British on the other, or to break off the siege altogether, thereby giving the defenders a chance to attack the French from the rear.

Bussy advised Lally to keep his army intact, but Lally insisted on dividing the French forces. Coote slowly moved forward until his forces faced the French lines, with the mountain on his left and the fort on his right. The battle began.

The French cavalry attacked first but was driven off by the British guns. The French guns replied but were too far off to do any damage to the British infantry while the British artillery, better positioned and more accurate, began to inflict a heavy toll on the French infantry. The two sides advanced amid heavy musket fire followed by bayonet charges. Soon the ground was littered with the dead and dying while, all around, men were engaged in hand-to-hand combat. As a contemporary Indian account says, somewhat poetically, “... the decline of the world of life continued till the setting of the sun, and the world was caught between the jaws of death”.

Finally, the French began to withdraw and the British halted to regroup. At that moment, a direct hit on a French ammunition cart killed or wounded more than 80 men causing their withdrawal to become a retreat and then a rout, with the British troops in hot pursuit. The French army in India, as a result of this battle, was no longer a sustainable fighting force.

At the end of the day, Bussy had been captured and Lally had retreated in some disorder to Pondicherry, which itself fell the following year after the British had picked off the remaining forts one by one. The British lost about 65 men in the battle and the French about 600, and with it their hopes of a French empire in the East.

* * *

In 1783, after the Mysore Wars, the fort at Vandavasi was abandoned and blown up.

In modern Vandavasi, close by a temple wall and partially hidden behind some railing usually draped with washing, there are a cannon and plaque commemorating the action and they are all what is left of the battle of Wandiwash.

|