|

The 12-feet-high walls of the Institute of Mental Health, Kilpauk, may seem formidable to anyone on the outside, but there is a touching human story inside, in this sprawling 63-acre verdant campus with its over 200-year-old buildings. And in these surroundings I was on a fascinating historical journey of care for the mentally ill.

| Tamil Nadu, and Chennai in particular, today boast of world-class medical attention in many areas of medicare. Hospitals like the Institute of Mental Health, Kilpauk, and dedicated people behind them sowed the seeds of humanitarian attention to patients many decades ago. First of the three-part series is published today. |

It was Asst. Surgeon V. Connolly, Secretary to the Medical Board who, in 1793, proposed to the government plans to set up a Lunatic Asylum in Madras. The East India Company, the then administrative authority for Fort St. George and its surrounding areas, appointed Connolly to be in charge of the Asylum and lend his house to accommodate persons of unsound mind. The premises, taken on lease for Rs. 825 a month, were within the limits of ‘Poorshewak’* and comprised 45 acres of land at a nominal quit rent of 51 pagodas per annum.

The Asylum opened there on October 1, 1794 and was meant for mentally ill Europeans and ‘Eurasians’ (now called Anglo-Indians). Subsequently, Surgeon Maurice Fitzgerald held charge till 1803 and was followed by John Goulde. At that time, the institution could accommodate only 20 persons. It appears to have remained Connolly’s property till he sold it to Dr. Dalton, with the Government paying Rs. 828 a month for its use. Dalton rebuilt the whole facility, enlarging the accommodation, and it was called ‘Dalton’s Mad Hospital’. When he retired, 54 inmates were being taken care of in the campus.

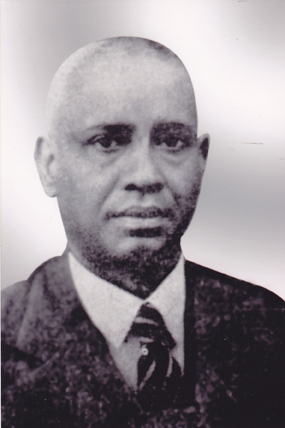

Dr. H.S. Hensman |

According to W. Ernst in ‘The treatment of the European insane in British India’ in Vol 3 of The Anatomy of Madness, “The accounts praising Connolly’s achievements are divided between mention of personal profit on the one hand and public benevolence on the other. Before embarkation he had also sold the property at three times the estimated value to another medical practitioner who expected the asylum to be a good enough source of income to imitate his predecessor’s rise to fortune.”

The government did not get involved in lunacy care till 1815, when Surgeon Dalton considered selling the place for a highly inflated price. It was held “that the principle of selling not only the building but also the charge of the patients in it to an individual, however qualified or personally unobjectionable, could not be sanctioned by the government” (Military Despatch 1823). Dalton was at the time “stuck with the asylum but on his retirement had to hand over medical charge of the institution to a surgeon who was appointed by government on recommendation from the Medical Board,” records Ernst. No more was heard of the subject (as far as I could find) till the establishment of the Madras Lunatic Asylum on a 66½-acre site in Lococks Gardens, just outside the then municipal limits, was sanctioned by Government on January 7, 1867.

Dr. J. Dhairyam |

The Asylum started functioning in the new premises on May 15, 1871 with 145 patients, and Surgeon John Murray m.d. as Superintendent with residential quarters inside the premises. The buildings, developed close together at a cost of just over Rs. 200,000, were based on the cottage or pavilion system, with blocks of single rooms and 12-15 persons in each block fairly close by. Wells inside the compound provided water till 1896, when the municipality took over this responsibility.

In the early years, while the ‘Diarrhoea Block’ housed patients with distressing and disabling non-specific enteritis and dysentery (very common in those times!), those with suicidal risk were segregated in the ‘Vigilance Block’ and intensely monitored by the staff day and night. Six ‘cottages’ accommodated paying patients in self-contained units comparable to the cottages of luxury hotels, with family members staying with them and even preparing meals. The Asylum, however, continued to be referred to as ‘Dalton’s Madhouse’ for some more time!

1892 saw the transfer of ‘criminal lunatics’ from the districts. There was an increase in the staff strength, and a few additional buildings and more cottages for paying patients were raised. That was ‘the period of custodial care’, as the primary concern of the authorities was to see that the persons committed to the Asylum did not harm either themselves or each other, and did not escape from the institution to be a source of danger to their fellow-citizens. Mechanical restraints like manacles, chains, etc. were in use. Only a small number of those admitted could be sent back to their homes as ‘recovered’ and, not surprisingly, the word ‘Asylum’ came to have a bad association. In 1922 came the change in name – from the ‘Government Lunatic Asylum’ to ‘The Government Mental Hospital’.

Dr. H.S. Hensman, who had additional training in Psychological Medicine, took charge as the first Indian (though he had his roots in Ceylon) Superintendent in 1924, ushering in more humane custodial care. The patient-attendant ratio had already been brought to seven to one by that time. Along with Dr. G.R. Parasuram, an alumnus of Edinburgh, who joined as his deputy, they took over the instruction on ‘Mental diseases’ to the undergraduate medical students who visited the hospital for two weeks during their final year of studies. During that time, the additional buildings constructed included a new ‘administrative block’.

The daily morning ward rounds by Dr. Hensman, a strict disciplinarian, it is narrated, bordered on a ‘religious ritual’. If a patient was seen with a running nose during his rounds, before noon the attendant had received notice that his services were terminated! It is also said that when the attendant represented that he had joined duty only a few days earlier, he was reinstated after he gave a promise that such lapses would not recur!

A view of a single room block in Female Section. |

In 1936, Dr. S. Venkata-subbu Rao, who had held appointments as Physician in teaching institutions for several years even after getting a Diploma in Psychological Medicine, succeeded him. However, it was in 1939 when Dr. J. Dhairyam took charge as Superintendent (the last Superintendent before Independence) that the system of admission of ‘voluntary boarders’ was introduced, “even before it was introduced in Britain”, states a veteran. Indigenous medicines were tried out on a large scale, as also the introduction of ‘convulsive therapy’ and insulin coma therapy.

In the men’s wards, however, ‘overcrowding’ went on unchecked, as patients who were brought after completion of the legal formalities could not be refused admission. Also increase in patients did not automatically lead to increase in staff. Previously, about one hundred patients in the men’s wing and a smaller number in the women’s wing were housed in what was officially termed as the ‘Men’s hospital’ and the ‘Women’s hospital’ which received newly admitted patients who were to stay there for a few weeks for observation and treatment, after which they were transferred to other parts of the hospital. Trained nurses were available only for these two parts of the hospital. The rest of the patients were looked after by attendants – mostly men, designated as warders – and the Deputy Overseers who, in turn, were responsible to the Medical Officers.

*According to the Madras Tercentenary Volume, the original hospital was “on the site, now (1939) known as ‘College Park’, and was till recently the residence of the Principal and staff of the MCC and is now the residence of the students of the MMC.”

Early Madras Christian College records note, “The Principal Miller’s bungalow and the College Park were located for many years in the Kilpauk area, possibly somewhere down the present-day Miller’s Road. Rao Bahadur Masilamony Mudaliar was to erect the hostel at a cost of Rs. 77,300. This Hostel finally came up at a property of eight acres, with a fine house, gifted by Miller. 40 students started living in this hostel, which also came to be known as Cosmopolitan Hostel because for the first time students of all communities started living together. It was inaugurated on August 26, 1919 by Dr Skinner just before he retired as Principal.” This site and hostels may have later been sold to the Madras Medical College.

(To be continued)

|