|

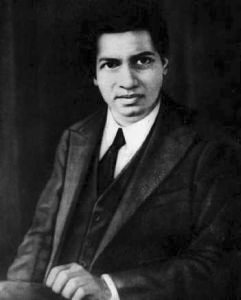

He came, he saw, he conquered and he left – all like a lightning flash. This is perfectly true of Ramanujan and his life. Prof. S.R. Ranganathan, former Assistant Professor of Mathematics, Presidency College, Madras, and father of Library Science in India, called Ramanujan a ‘Mathematical Meteor’. Great men come and go like meteors. They shine and consume themselves prematurely. Ramanujan’s birth, his amazing activity in Madras and Cambridge, and his death, all seemed to have happened in a flash.

Srinivasa Ramanujan |

The super genius Ramanujan was born on December 22, 1887 in a poor Aiyangar family. His father was an ill-paid accountant in a cloth merchant’s shop in Kumbakonam. Ramanujan was brought up in a strictly orthodox tradition of a South Indian Brahmin family. Admitted to school at the age of five, he later joined the Town High School, Kumbakonam, where he studied for nine years.

It was during his school days that his extraordinary talent came to the surface. At twelve, he was able to solve all the problems in Loney’s Trigonometry without any help from anybody.

In 1903, he got a copy of Carr’s Synopsis of Elementary Results in Pure and Applied Mathematics. This book contained 6165 formulae without proofs in Algebra, Trigonometry and Calculus. Ramanujan worked out all of them, each being a research by itself. This was the starting joint of his mathematical career.

In December 1903, Ramanujan passed his Matriculation examination of the Madras University in First Class.

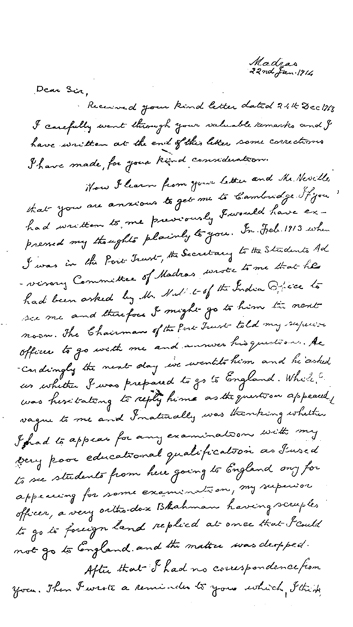

Ramanujan's original handwritten letter...

... reproduced here for easier reading |

The first public recognition of his extraordinary powers was on the occasion of the annual prize distribution in 1904. Krishna Iyer, the Headmaster, introduced him to V. Krishnaswamy Iyer, the President of the function, and to the distinguished audience in these terms: “Here is a student who my Mathematics Assistant says has displayed in his answer papers a remarkable agility and super intelligence and deserved more marks than even the maximum itself.”

Ramanujan joined the Government College, Kumbakonam, and the Subramanian Scholarship he received helped him continue his studies undisturbed. But he was so immersed in Mathematics that he did not study any other subject. Thus, he was an academic disaster. He failed in English, getting only 3%. That led to the cancellation of the scholarship, bringing him under financial strain. To compensate the loss of income from scholarship, he took to tuitions, but here too he was a failure. He talked way above the heads of the students and they stopped coming to him. But he could not stop the mathematical mysteries that throbbed in his head. He worked on them feverishly, often hiding under the cot to escape his parents’ wrath. He kept telling them that the Goddess Namagiri was inspiring him.

Disappointed by what had happened in Kumbakonam, he made his way to Pachaiyappa’s College in Madras. Here, too, he fared poorly, unable to concentrate on anything except Mathematics. He used to tell others that the problems given in the Geometry, Algebra and Trigonometry textbooks were all mental sums. He rarely got more than 10% in Physiology for which he had supreme contempt, no more than 15% to 20% in Greek and Roman History and he just managed to get 25% in English. Professors used to ask him, “Can’t you improve?” Ramanujan failed here too – and that was the end of his formal education.

Ramanujan’s family was then under severe financial strain and a job for Ramanujan had become a necessity. But it was very difficult to get one without any qualification. He stayed with K.S. Visvanatha Sastri (one of his friends) in the hostel. At nights Ramanujan would be so depressed that he would tell his friend that while many great men like Galileo died as a consequence of the Inquisition, he would die in poverty.

Ramanujan tried to contact mathematicians in Bombay, but could not get a positive response as his results were often quite off-beat and were not deduced systematicallly, step by step. That only depressed him further.

* * *

The turning point in his life was his introduction to R. Ramachandra Rao, the Collector of Nellore. Rao was also Secretary of the Mathematical Society. All the theorems written in notebooks given to Rao were unknown to scholars, Rao stated after being unable to make anything out of them. Even though Ramanujan became further depressed after this negative response, he continued to meet Rao and, after a number of interactions, Rao became convinced that Ramanujan was a remarkable person. When Rao asked Ramanujan what was it that he wanted, Ramanujan replied that all he wanted was a pittance to live on so that he could pursue his research. At last, on the recommendation of Rao, Francis Spring, the Chairman of Port Trust, Madras, appointed Ramanujan as a Clerk in the Port Trust Office on a salary of Rs.25 a month and Ramanujan was very happy he got a job.

He continued to worship Mathematics during his employment. Unable to buy all the paper he needed for his work, he did the equations on discarded Port Trust wrappers. At times he even used red ink to write over earlier writings. While working in the Port Trust, he had the distinct advantage of having as his mentor a Narayana Iyer, the Manager, who was also the Treasurer of the Indian Mathematical Society.

Narayana Iyer’s son Subbanarayanan narrated the following:

“Every night both Ramanujan and my father used to work out mathematics on two big-sized slates sitting on a small parapet upstairs till 11.30. The noises of the slate pencils used to be music for my sleep. Several nights, Ramanujan used to get up at 2’o clock and note down something on the slate in the dull light of a hurricane lamp. When he was asked about this, he would say that he worked out mathematics in his dreams and now he was jotting the results on the slate to remember.” Ramanujan believed Goddess Namagiri was responsible for his dreams. He and his family were ardent devotees of God Narasimha, the sign of whose grace was in drops of blood he saw during his dreams. Ramanujan stated that after seeing such drops, scrolls containing the most complicated mathematics used to unfold before him and that he wrote down on waking only a fraction of what was shown to him.

The Journal of the Indian Mathematical Society was responsible for publishing Ramanujan’s various articles. His earliest contribution to the journal was in the form of questions (Vol. III-1911). This was followed by a long article ‘Some properties of Bernoullis numbers’. A number of articles followed from time to time.

In the meantime, in 1909, 22-year-old Ramanujan, a short, plump man with a big head and bright and burning eyes, with his long hair combed and knotted according to ancient Brahmin custom, married nine-year-old Janaki Ammal.

By then he was so absorbed in Mathematics that he did not stop even to eat. Janaki or his mother used to feed him at mealtimes.

When Dr. G.T. Walker f.r.s., head of the Meteorological Department and formerly Fellow and Mathematics Lecturer of Trinity College, Cambridge, visited Madras in 1912 on an official work, Francis Spring who knew of Ramanujan’s work, brought to his visitor’s attention the endeavours of the young man. Sensing the extraordinary abilities of Ramanujan, Walker arranged a research scholarship of Rs. 75 a month from Madras Universtiy for a period of two years so that Ramanujan could pursue research without any financial strain.

As India at the time was a Mathematical backwater, there was no one in the country to assess his work or provide intellectual stimulation. He was advised to send his work to England, one of the main centres of Mathematics in the world at the time.

Ramanujan wrote to several mathematicians in England a number of times, but there was no proper response Encouraged by Narayana Iyer, Ramanujan then wrote a letter to G.H. Hardy, a Fellow of Trinity College, Cambridge, at the time and a renowned mathematician. This letter written in 1913 was to change Ramanujan’s life forever.

With the letter to Hardy, Ramanujan (a stranger from India, as far as Hardy was concerned) sent 120 mathematical theorems that he claimed he had discovered. He asked Hardy for his opinion on them. Hardy used to get letters from cracks claiming to have solved all kinds of problems and Hardy thought this letter was just another of them. So he glanced at it with distaste. Many of the theorems made no sense. Of the other theorems, some were already known. Hardy decided that Ramanujan must be some kind of a fraud and threw the letter aside.

But all that day the letter kept nagging Hardy. Might there be something in those wild-looking theorems? He called for his fellow mathematician, J.E. Littlewood, and the two set out to assess the Indian’s worth.

By midnight they found out or, better, discovered the truth. Ramanujan was a genius. Hardy later explained that many of those fantastic theorems had to be true because no one had the imagination to invent them. This was a turning point in the history of mathematics. An obscure Madras Port Trust clerk became a Cambridge scholar and went on to be recognised as one of the most amazing mathematicians the world has known.

|