|

Almost everything modern, including geography, got air-dropped inside Papua New Guinea (PNG) when charters by biologists and miners first flew over the interiors of this country in Oceania in the 1930s. From up in the air to when they landed, they stared at dark races unknown to the outside world. Almost 50 years later, when K.V.S. Krishna travelled into this still-primitive country below the equator to land in the capital, Port Moresby, the last thing that he was expecting was Dravidian déjà vu. Yet, within days of his arrival, this visitor schooled in Chennai, whose mother tongue was Telugu, was stunned when he heard the familiar tinkle of Tamil, 8000 km from his home State, in faraway PNG, a country yet to be fully explored by man.

The first day when he met the Chairman of his company, Sivarai Domu, “I told him your name means Shiva Stone in my language,” says Krishna, “and we laughed it off.” An experienced planter who had worked in Indonesia, Sri Lanka and Cameroon, Krishna had been invited by the National Plantation Management Agency to set up cardamom estates in PNG. A land blessed with 300 wet days in a year and 300 inches of rain, it is a spice grower’s utopia. While Krishna thought he’d get by with Pidgin English in this alien nation that had 750 indigenous languages, he kept finding Old Dravida as he went deeper inland.

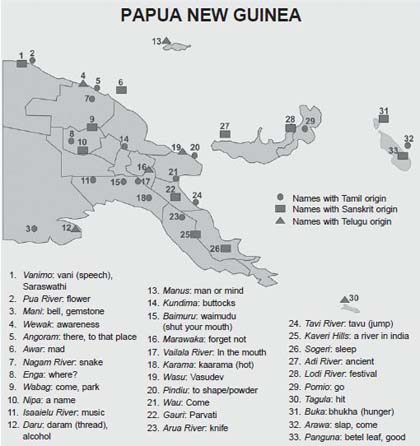

“I travelled to Goroka, though a hill gap called ‘Ashaloka’ to land at ‘Ramu’ Valley. We reached a Christian Mission called ‘Brahman Mission’. They handed me a land document called Bumi No 11. …We kept passing towns whose names had Tamil meanings ... Wau (come here), Karimui (blackface) and Keveri Hills,” he recalls. Even a place called Linga Linga, a name that soaked straight into the soul of this Shaivite. Other words, like erave (sun), nagam (snake) and pua (flower) sounded like the whispers and shouts from the streets and bazaars of Mylapore, the cultural hub of Chennai.

Even the surnames sounded like Dravidian descriptors with a Christian prename, John Kulala (short man), Tom Muliap (muli means radish or corner) and Nat Koleala (hen man). The parliament house was at Waigani (mouth intellect). When he met the Prime Minister, Rabbie Namalue, “I told him your name means you are ‘our man’ in Tamil.” When he heard a man being called Kittappa, which means ‘near-father’ in Tamil, and ‘father-in-law’ in New Guinea, Krishna’s mind went into a spin. He was convinced that his Dravidian dictionary had an uncanny phonetic and grammatical resemblance to a Guinean glossary. Spoken aloud, these words sound almost like ancient Indian incantations.

Linguists believe Guinea was the home of 45 per cent of the world’s languages. Without a script, without being committed to paper, most are near extinct. But how had this lexicon sprung up without any linguistic, racial or trade connection between India and PNG? Diplomatic relations were established only in 1976, four years before Krishna’s arrival. Yet, when Krishna met the Premier of Madang, who loved chewing arecanuts, and offered him a supari as we do to guests in India, the honoured Guinean thought Krishna had gone native!

But the primary purpose was to grow spice in this country that had missed the Bronze and the Iron Ages and major inventions like the wheel, pottery and woven cloth. Krishna’s immediate focus was airlifting cement, sand, bricks and fertilisers to build factories. For seven years in this planter’s paradise where tea registers the highest yield, he says, “We got 1000 kilos of cardamom per hectare and four times the amount of coffee than we get in India.” All this, while some of the natives still lived life in a naked state and used stone tools till the 1980s and cooked their food by digging holes in the ground. When George Rosario, the first plantation manager, grew a jackfruit tree to remind him of Kerala, farm workers called it pig fruit.

After Krishna’s return to Chennai in 1990, this self-professed “map minded chap” spread out the Guinean atlas in his home. His table-top survey almost knocked his vest off. “Almost 20 per cent of the towns, districts had a Dravidian connection (Tamil, Telugu and Sanskrit). Even the telephone directory had about 50 Tamil surnames,” says this 76-year-old whose voice is now slightly frail, but whose mind is still sharp and inquiring.

One connection might have been a coincidence. But over 300 names that encompassed political and physical geography are terms of towns, rivers, mountains and even animal names. Krishna was certain there had to be some missing link. Unlike everywhere else, where they had mutilated names of towns, the British and Australians allowed ancient names to endure in PNG (unlike Australia where the Aborigine names have been near-erased). And while languages in PNG slowly died out without ever having had a script, however, painted road signs, land maps and town certificates in English point out the hoary past. Only Krishna could see the light of meaning on these paths; “having lost their languages, the Guineans did not know the significance of these words any more,” he says.

In nearby Indonesia and South Asia, shipwrecked aspects of ancient India hit you like flotsam, like when you hail a cab for Ram and Erawan Place (brother of Ravana). But the language of PNG predated our epics and the Ramayana; it is pre-Harappan or proto-Dravidian. To study the genesis of this geography, this retiree travelled back in time, trawling through geological events, evolution and the first migrations of mankind. Early this year, after ten years of research, this one-time botanist and full-time hobby-historian looked up from his computer muttering, “Maybe genes won’t lie.”

Having excavated history from language, Krishna made a power-point presentation to the Tamil Nadu State Department of Archaeology in Feburary 2009, tracing the migration of man out of Africa 70-80,000 years ago into India, some 20,000 years after the larynx had developed in anatomically modern man. They lived in India before moving on to Papua New Guinea and Australia, carrying a language that had crystallised here. Some of these are cognate words, language-pairs such as po (go), as they still say in Tamil and in PNG. Kalvettu, the official journal of the TN State Department of Archaeology, published his paper last year.

His observations do have some resonance. The Central Institute of Classical Tamil is exploring the linguistic, cultural and anthropological affinities between Tamil/Dravidians and Australian Aborigines. PNG and Australia were connected landmasses until the shallow Torres Strait separated them.

Krishna is aware it’ll take more than a sound understanding to get to the genesis of Dravidian Geography. “Who knows if this is coincidence?” he says, debunking his years of research. But you can tell from his voice he’s hoping it’s not, that perhaps paleontologists, archaeologists and anthropologists will one day uncover the missing links. He is still holding on to visiting cards of men like John Kalula (short man). Krishna wants to reach out to Kalula, when there’s some confirmation about their long lost brotherhood. – (The article and the base map first appeared in Open, the weekly current and feature magazine.)

|