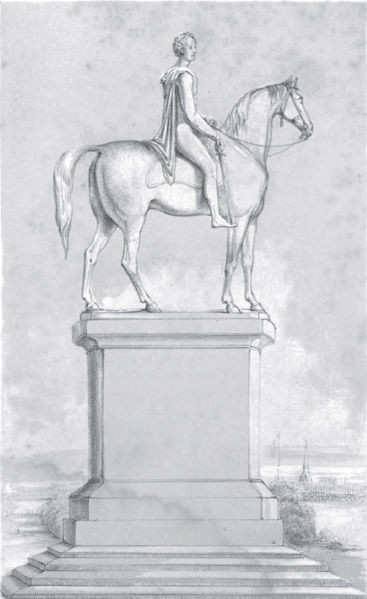

A sketch of the Munro statue. (Courtesy: Historical Record of the Honourable East India Company's First Madras European Regiment by James George Smith Neill (1843). Published by: Smith, Elder and Co.)

|

Sir Thomas Munro, Governor of Madras, died on July 6, 1827. He was buried the next day at Gooty in present-day Andhra Pradesh. Munro was of a rare breed – a genuine friend of the Indian. His death was, therefore, the occasion for universal grief in the Madras Presidency. The Governor's Council met in Madras and decided that there ought to be several memorials to Munro. Chief among them were a tank and a choultry at Gooty. The latter was to have a permanent establishment of servants for its maintenance and they were also to provide water to thirsty passers-by. In addition, trees were to be planted and wells dug around the spot where Munro was buried. A stone monument was to be built above Munro's resting place. Madras city, it was decided, would have a bronze statue of Munro. This decision was published in the extraordinary Gazette of Fort St George dated July 9th.

Almost immediately, subscriptions began pouring in. Accounts vary as to the extent of the collection; some put it at Rs 30,000, others claimed it was Rs 180,000. But what is certain is that £ 8000 was appropriated from this for the commissioning of the statue. A committee comprising John Ravenshaw, Alexander Read and Colonels Blackburne, Cunningham, Wilkes and Scott was formed to see the project through. Ravenshaw, who chaired this committee, was a civilian of many years' standing and was considered a disciple of Munro. He was to later become Chairman of the East India Company.

The committee decided to entrust the task to Francis Chantrey. Born in 1782 near Sheffield, Chantrey was from very humble origins, his father having been a carpenter. Trained in wood carving and painting, Chantrey did both for some years before he discovered his innate talent for sculpting and clay modelling. From 1807 he became a full-time sculptor specialising in busts. He later travelled to Italy where he learnt how to sculpt life-size figures and by the time of Munro's death he was a very busy man.

"Recd an order from the Committee of Management through J.G. Ravenshaw Esqr. Chairman for an Equestrian Statue in Bronze of Sir Thomas Munro – place of Erection – Madras, dimensions not less than 10 feet high," reads Chantrey's ledger entry for October 20, 1828 (as published in the Walpole Society's 56th volume, 1991). The taciturn entry does not reveal it, but Chantrey was not comfortable sculpting animals. "Modelling horses gravelled Chantrey," wrote a none-too-complimentary analysis of his works (The Eclectic Magazine of Foreign Literature, Science and Art, Vol 2, 1843); "he was at home with men, but he had to learn a new line of art when it came to manufacturing horses." It was perhaps true, for out of 35 or so sculptures of Chantrey that survive, only three were equestrian – those of Munro, the Duke of Wellington and King George IV. The same account also enumerates what Chantrey received for his three equestrian works – £10,000 for the Duke, £9000 for the King and £8000 for Munro. It also states that, among the three, Munro's figure was the finest while that of the horse was the worst; it was the reverse in the case of Wellington!

Chantrey's studio was obviously full with orders for he took his time to execute Munro. In any case, he appears to have been reluctant to quote "an exact period," as is evident from his negotiations in 1837 for getting the contract to execute the Duke of Wellington's statue. Then, as reported in the Literary Gazette and Journal of the Belle Lettres, Arts, Sciences, etc, he had indicated a rough period of four years to execute the statue, provided "No accident happened in casting the bronze." But for Munro, he appears to have taken ten years. Work began in 1828, for the Athenaeum of that year, while noting that Chantrey was in Brighton erecting a statue of the King, mentioned that he was also executing the Munro commission.

The order for the equestrian statue of King George IV had come to him a little earlier than the order for Munro statue. The King had been impressed with Chantrey's abilities while modelling for a bust and had sounded him out about a statue depicting him while riding. Chantrey had accepted the contract and, in order to accommodate a much larger task than usual, had made considerable alterations to his studio and expanded the capacity of his foundry, both located at Eccleston Place, London. The arrival of the Munro job meant he could apportion costs across the two and thus reap higher margins. Completed in 1828, the foundry was a model of its time, with capability to cast statues up to 12 feet and having cranes to move them around.

Chantrey had two devoted assistants, Allan Cunningham and Henry Weekes. Of these, the former faithfully noted down his employer's methods while working on a commission. Sir Francis Chantrey RA, Recollections, His Life, Practice and Opinions, by George Jones RA and published in 1849, was to rely heavily on Cunningham's recollections. He noted that upon being handed the Munro order, Chantrey was "embarrassed by the conflicting opinions of his friends and visitors. Some wished a horse in the classic style; some, a steed like that of Marcus Aurelius; some, an Arabian; others, a large war-horse; and many, nay, the greater part, a specimen of blood, fit for Newmarket, but very unfit for sculpture; so that in endeavouring to diminish flesh for one connoisseur, and to increase bone for another, for a third to lengthen the legs, to even the line of back and to elongate the neck for a fourth, the sculptor became confused, and materially injured his work, by departing from his own good sense, and yielding to inconsiderate criticism." A couple of mishaps later, he cannily settled on a horse from King George IV's stable and it was to do for both the statues, thereby saving him time and effort.

As for the posture of the horse, tradition dictated that Munro being a fine horseman, who had died of natural causes, he had to be depicted on horse that had all its feet on the ground. Chantrey remarked to Cunningham that he hoped "to achieve the sentiment of a horse standing still in a field, and looking about him: if I can hit that I shall do." The process of casting was written in great detail by 'C' (probably Cunning-ham) and published in the Madras Journal of Literature and Science, 1840. Chantrey first created a life-size clay of the horse and kept it aside for four years. He would keep going back to it for some improvement or the other and it was the task of Cunningham to keep the clay "in a proper state of moisture", not "bake dry in summer or freeze hard in winter." When the sculptor was finally satisfied, a mould in Plaster of Paris was taken and the clay model broken up and used in other commissions (nothing was ever wasted by Chantrey).

Sculpting Munro was the next challenge. The only reference was a portrait by Sir Martin Archer Shee and that presented only one point of view while a sculpture needed to be seen from all sides. Chantrey took his time over it and showed the work to everyone (including perhaps Lady Munro) familiar with Munro's face and form and considered the task complete only when "not one objection has been raised to the fidelity with which he has caught up the likeness of a man he never saw." Munro's raiment, it was decided, would be a mix of the "ancient, the modern and the military." When all was done, Munro's form was cast in Plaster of Paris.

The next task was to form moulds of the statue in material that could withstand the heat of molten bronze. This was done using a mix of brick dust and plaster, which was around 10 to 12 inches thick. Inside, a core of the same material, with dimensions around an inch less than the final statue, was placed. The horse was moulded in five pieces, while Munro was in three. The two, the outer mould and the core for each of the pieces, were then baked in immense ovens with repeated tests to ensure that all moisture had been removed. Finally, when Chantrey was satisfied the moulds were buried in pits underground with tight sand packing allowing for two or three runners through which molten bronze from the furnace was allowed to flow in, from the bottom to the top.

After cooling, the sand was removed, the mould broken and the cast pieces of the statue were extracted. They were then polished with files and sandpaper to a golden hue, before being "deadened to their present hue by an application of muriatic acid and potash." The pieces were then joined together by filling the interior with sand and pouring molten bronze along the edges to be joined. Munro and horse were ready. The tail, the sword and the stirrup, according to 'C', were made separately. Which brings us to a mystery. If a stirrup was cast, where did it vanish in the final execution? Was it lost in transit? Apparently not and 'C' was probably mistaken, for none of the three equestrian statues of Chantrey showed the rider with stirrup or, for that matter, a saddle.

The statue was ready for public viewing by 1837. And Chantrey made sure that every-one who was someone viewed it. He was hoping to land more commissions for equestrian statues. The Government of Madras was growing impatient but Chantrey would not budge. He stated that he would not send the statue if he was not given details of the place where it was to be erected. While waiting for the answer, he continued flaunting the work.

Among those who came was the Duke of Wellington. There was talk of an equestrian statue for the Duke and Chantrey wanted the contract. The committee, in which Chantrey's friends were in a minority, had left it to the Duke. He came, gazed at the work for a while and then remarked that it was "A very fine horse." Then, after a while, he said it was a very fine statue and, then, having stood silently beside Munro for a while, said that he was "an extraordinary man." That swung the vote in Chantrey's favour. He was all for using the same horse! But Allan Cunningham dissuaded him. The Wellington statue was incomplete at the time of Chantrey's death and was finished, new horse and all, by Cunningham. Chantrey's last wish was to execute yet another statue of the Duke to be erected in Glasgow. He wanted to use the same horse there as well! But the Scots would have none of it and so he lost the contract. If all had worked Chantrey's way, it would have been the most modelled horse in history.

The Gentleman's Magazine of 1838 waxed eloquent on the statue. Claiming that at 15 feet it was the tallest equestrian statue in the world, it noted that the "horse was calm and at gaze, while the rider sits contemplating some distant object, in quiet self-possession. The horse, though still, seems about to move forward and the rider, though thoughtful, to start into action."

Not everyone was as impressed. Frances William-Wynns, a society lady, noted in her diary that it could not be called the finest equestrian statue in the world, for the works of Michaelangelo far exceeded it in quality. She opined that the horse had a thick jowl and while the face was copied from an Arab steed, the legs were those of an English hunter and, so, out of proportion. She felt that these weaknesses would not be noticed once the statue was mounted on its pedestal.

By early 1838, Chantrey began making preparations for the statue's journey to Madras. And in the city that was to be its home, arrangements were being made to receive it.

(To be concluded)

|