|

(Continued from last fortnight)

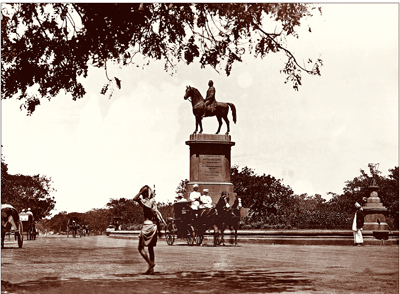

The chosen location for the Munro Statue – The Island

(Picture: Vintage Vignettes).

|

Chantrey, as we noted last fortnight, had delayed sending the statue of Sir Thomas Munro to Madras on the pretext that he was not certain as to the exact location planned for it in Madras. And certainly there appears to have been changes in plan in Madras from time to time. In 1829, shortly after the commission to execute the statue was given to Chantrey, the Government of Madras began debating on where it ought to be located. The Madras Courier noted on 18th November that year that a new road, "which will afford a delightful evening drive and a promenade on the sea beach" was being formed. The thoroughfare, it noted, would run through Government Gardens (the present-day Government Estate and the location of the unwanted new Assembly), pass around Marine Villa and along the beach up to the saluting battery, "in the neighbourhood of which a cenotaph is to be erected, whereupon will be placed the statue of Sir Thomas Munro." If this had happened, Munro's would have been the first statue on the beach.

Ten years later, it was decided that the statue would be located midway between Government and Wallajah Bridges, to meet the express desire of the Governor, Lord Elphinstone. The Asiatic Journal and Monthly Miscellany (1838) reported, "Preparations to receive Sir T Munro's statue are carried on with considerable activity. One half of the circular road around the site has been finished, and the foundation for the pedestal, which is sunk about ten feet below the surface, and measures twenty-nine by twenty-two feet at the bottom, is on a level with the road."

The base had a story that was independent of the statue. In July 1836 the Calcutta General and Monthly Register recorded that "Chantrey's plan for the base of Sir T Munro's statue has been received by the committee." This was not the pedestal which was Chantrey's work but what was below it. The work was entrusted to the local firm of Ostheider's, which operated from 34 Mount Road. Accounts vary as to the precise nature of the firm's business. They are classified variously as architects, masons and stonecutters. The Ostheiders were an old Madras family, probably of German origin, and some had been prominent in Freemasonry. The business was in existence till 1897. The base of the Munro statue comprised three short steps going all around, with seven indentations in it to receive the pedestal.

In the meanwhile, back in England, Chantrey busied himself with preparations for the despatch of the statue. It was to journey to Madras on The Asia. It was not travelling alone. Keeping it company during the journey was an enormous statue in marble of Bishop Heber, also by Chantrey and bound for Calcutta. The Asia was a ship with a long history of journeys from London to Madras, Calcutta and back. Ironically, it had been the ship on which Munro had booked his passage home shortly before his death.

"To account for ropes and slings for putting the statue on board The Asia here and removing at Madras," was an entry in Chantrey's ledger. But his true emotions on dispatching the Munro statue was evident in a letter he wrote his friend Charles Turner, the artist, on April 10, 1838, the day the statue was to leave. The letter timed 7.00 am exults: "IT is done! ! ! and well done ! ! ! Had it lasted for a few days longer it would have done for me! I hope to meet man and horse in the East India Dock soon after eleven to-day, and dine at Lovegrove's, when I have seen them on board the "Asia." Come if you can. Truly yours,".

In February 1838, Francis, the son of Chantrey's assistant Allan Cunningham, had obtained his cadetship with the Madras Engineers. Prior to his sailing for Madras, Chantrey briefed him on the intricacies of erecting the statue. Francis Cunningham was therefore on hand when The Asia reached Madras. The city, of course, did not have a harbour and The Asia docked two miles in Madras Roads, two miles out at sea, and awaited the catamarans and masula boats to come and offload its cargo.

The Munro statue at six tonnes was the single heaviest consignment received in Madras till then. It therefore required special handling and the Madras Government entrusted the task to a Mr McKennie. He was then Acting Master-Attendant and was in the process of studying the stone breakwater that had earlier been constructed to protect ships that docked off Madras. He was an expert on "currents, tides, set of the sea and the rise and break of surf" (The Nautical Magazine, 1841) and ideally suited for the task of landing Munro. He was to do the job so well that he "received a handsome acknowledgement of his services from the people of Madras."

It was to be a three-day operation. The United Service Gazette of September 3, 1838 recorded that "great praise is due to the Officiating Master-Attendant and the officers of The Asia, for the careful and seaman-like manner in which the Munro statue was hoisted up and safely landed; the horse was brought on shore last Thursday, the figure on Friday and the granite pedestal would have been landed on Saturday, but for the uncertain state of the surf, which rendered it necessary to defer the undertaking." All three were brought on shore opposite the office of Arbuthnot & Co (present day site of the Indian Bank on First Line Beach).

The actual drama involved in the transporting of the statue over the surf is not in any published record. But in 1855, when the next largest consignment arrived, it was faithfully noted. That was the arrival of four steam engines for the Madras Railway Company, each of 13 tonnes. The Governor witnessed the offloading, for such was its significance. An extract of some relevant portions gives us an idea of how the Munro statue could have been brought ashore.

"A huge raft had been prepared for the purpose. The apparatus on board for raising the engines from the hold consisted of strong shears – one pair over the hatchway for lifting them, and another on the ship's side for lowering them over upon the raft…(the engine) was easily lifted and sent over the side; but some difficulty was experienced in fixing it properly on the raft so as to be exactly in its centre. The raft was balanced at length by means of outriggers attached to it, and with its freight was towed ashore." (The Indian News and Chronicle of Eastern Affaires, 1855)

There are no documents in the public domain on where the statue was stored in Madras during the one year that it took before it was finally erected at the chosen spot. Also, the process of fusing the horse and rider which must have been in the hands of Francis Cunningham is also not recorded and so too the method by which the statue was fixed on the pedestal.

What we hear next is from a report in The Asiatic Journal and Monthly Register for British and Foreign Affaires (1839). "Sir Francis Chantrey's magnificent statue of Sir Thomas Munro was opened to public view on the evening of October 23, under a salute of seventeen guns. The greater portion of Madras society was present on the occasion, besides an immense concourse of natives. On this occasion a very large party of the subscribers to the statue were entertained by the Governor in the banqueting-room."

After seeing the statue safely installed, Francis Cunningham was to have a distinguished career in India. He and his elder brothers Joseph and Alexander were all to serve here, thanks in part to the writer Sir Walter Scott who was friendly with Robert Dundas of the East India Company's Board of Control. After active service in the Afghan War, Francis Cunningham moved to Mysore where he became Secretary of the Mysore Commission and assistant to Sir Mark Cubbon, the Chief Commissioner, Bangalore. He played an important role in the development of the Lalbagh Horticultural Gardens, Bangalore, and Cunningham Road in that city is named after him. He was to be a lobbyist for the restoration of Mysore to the Wodeyars. Cunningham died in England in 1872.

Munro's statue has continued to remain a witness to the changing topography of the Madras skyline ever since. The absence of the stirrup and the saddle has given rise to the legend that it was on account of oversight on the part of Chantrey and that he committed suicide because of this. Chantrey died, in fact, of natural causes. He had a heart disease, which was not diagnosed. The Times, London (28.11.1891), stated that on the evening of the 25th the sculptor had just returned from installation of a statue of the Bishop of Norwich and was "conversing freely when he suddenly sank into a chair and expired without a groan." The sudden death may have caused the rumour of suicide. (A fevered imagination can easily conjure up a scene of Chantrey talking happily when he receives a letter from someone in India. "All is lost," says the letter. "They are asking about the stirrup." Whereupon Chantrey opens a small vial of poison he carries on his person, drinks it before his companions can figure out what he is up to, totters to a chair and dies.)

It must be placed on record that not everyone was impressed with the statue. The Literary Gazette and Journal of Belles Lettres, Arts and Sciences, the sculptor's routine critic, made fun of Munro's sword resting on his foot and suggested that the sculptor ought to be called 'Stick-foot Chantrey'. Native opinion was also not favourable. In Indian tradition it was unthinkable that great men could have statues without a protective canopy over their heads. The Indian concept of kingship demanded a chattri or umbrella over the ruler. British Governors of Madras while going walkabout had a roundel over them. Illustrative of this is a story from Captain Albert Henry Andrew Hervey's Ten Years in India or The Life of a Young Officer, Vol 3 (1850) –

"I was one day driving by the monument when I saw an old man in a red coat, with three chevrons on his right arm. Standing leaning on his staff, and gazing silently on the exalted statue. He was evidently an old pensioner, not only from his dress, but from a certain degree of military carriage in his tout ensemble, which there was no mistaking. Out of curiosity I stopped my buggy, got out, and addressed the veteran. 'What are you looking at, my fine old fellow?', enquired I. 'Do you know who that is intended to represent?' 'Who can have known the great Sir Thomas Munro?,' replied the old man, 'without remembering him? And who can have known him without loving him? And how can I, who had served under him for many years, ever forget him?'

'Then you think that is a good likeness of our Governor? You recognise the face?' asked I.

'Yes sir', said he. 'It is a good likeness, but we shall never again see any like him. He was indeed the friend of the Indian, whether a sepoy or a ryot at the plough. And Madras will never again have a Governor like him.' And raising his hand to the head, he gave the old-fashioned salute, lifted up his bundle and walked off, mumbling to himself about the impropriety of crows being allowed to build nests on the top, and to do dirt over the head of the greatest man of his age."

Not everyone saw it that way. In his Omens and Superstitions of Southern India (1912), Edgar Thurston noted: "In Madras, a story is current with reference to the statue of Sir Thomas Munro, that he seized upon all the rice depôts, and starved the people by selling rice in egg-shells, at one shell for a rupee. To punish him, the Government erected the statue in an open place without a canopy, so that the birds of the air might insult him by polluting his face."

The statue became one of the sights of Madras. Despite a bad cold and having only a few hours in Madras, the humorist Mark Twain was driven to see it when he disembarked briefly in the city en route from Calcutta to Cape Town on April 11, 1896. Back on the boat, he was interviewed by a Madras reporter and he wanted to know who "the Roman General on horseback on one of your broad roads" was. For that matter every tourist guidebook mentions the statue without fail even today. Perhaps we need a plaque on the side explaining who Munro was and why he is commemorated.

(Concluded)

|