What a difference in engineering!

|

|

John Goldingham

|

The recent Transit-of-Venus reminded me that it was time that we remembered Madras's splendid contributions and achievements to a similar event in the 19th Century as well as other astronomical researches. The Transit-of-Venus across the disk of the Sun is a rare event in space. Only eight such events have occurred since the invention of the telescope: 1631, 1639, 1761, 1769, 1874, 1882 CE and the most recent ones in June 2004 and 2012. We have read before in Madras Musings, XIX: 20, 2010, of Chintamani Raghoonatachary (CR) and his part in the Transit-of-Venus observation expedition in 1874. So, today we recall the first Superintendent of the Madras Observatory (MO), John Goldingham, a shining scientist.

Goldingham was in 1802 appointed the first designated Astronomer of the MO. Born in London in 1767, he was hired by Michael Topping as his deputy in 1788. Goldingham was a trained mathematician, who was equally proficient in astronomy and engineering. He married Maria Louisa Popham – niece of Admiral Riggs Popham – in St Mary's Church in Fort St. George in 1796. Goldingham was directed to build the observatory in Madras in 1792 because of his civil engineering skill. He became the Presidency's Civil Engineer in 1800. He headed the Madras Survey School, which subsequently grew into the Madras Engineering College, Guindy. He died in 1849.

The English East India Company (EEIC) established the Observatory in 1792 ushering a new era of space exploration in India. This facility became possible through the efforts of William Petrie, a member of the Madras Government, who, in 1788, had built a private astronomical observatory. When Petrie returned to England in 1789, he donated the astronomical instruments he owned to the EEIC government in Madras. Charles Oakley, President of the Madras Council, proposed that the Madras Observatory needed to be developed to promote know-ledge of astronomy, geography, and navigation in India. The designer of the Observatory, Michael Topping, officiated as Astronomer until John Goldingham was formally appointed in 1794.

The Madras Observatory was the first of its kind in India. Other Indian observa-tories came up later: the Royal O, Lucknow (1835, short lived only up to 1849), the Rajah of Travancore O, Trivandrum (1842-1865), Captain W.S. Jacob's O, Poona (1842–1862), St. Xavier's College O, Calcutta (1875-1918?), Maharaja Takhtasinghji O, Poona (1882-1912), Hennessy O, Dehra Dun (1884-1898), Solar O, Kodaikanal (1901 to date), and Nizamiah Observatory, Hyderabad (1901-1954). An observatory in Calcutta at the Presidency College came up in 1905.

Goldingham made the earliest formal meteorological observations at the MO in 1793. He established a register at the Observatory to record detailed long-term barometric-atmospheric pressure readings. The data are available for 1796-1843. Goldingham maintained this register until 1825. It was continued to be maintained up to 1843 by Thomas Glanville Taylor, who succeeded Goldingham in 1826. Goldingham obtained barometric-pressure readings at sunrise, 1000 h, 1200 h, 1400 h, and at sunset every day. From these data, he calculated daily mean and monthly values of pressure corrected to temperature using the thermometer connected to the barometer. Additional notes included in this register refer to occurrences and strengths of storms in 1796-1821. For example, the register has details of low-atmospheric pressures that occurred in May-June 1813, October 1818, and in May 1820. The MO became internationally known for its general star catalogues published in two volumes by Goldingham.

Standard time

A particularly significant contribution Goldingham made while at the MO was ascertaining the 'time' for India in relation to Greenwich Mean Time (GMT). Goldingham established the longitude of Madras in 1802 as 80°18'30" east of the Greenwich Meridian. Consequently, the MO's clock supplied the standard time for the whole of India. At 2000 h every day, a gun fired to announce that all was well with the standard time. The clock at the MO was directly connected to the gun and triggered its firing.

Indian Standard Time (IST) is the time followed at present throughout India, 5½ hours ahead of GMT. IST is calculated on the basis of an 82.5°E longitude from a clock tower in Mirzapur (near Allahabad). During the British period, India followed four different time schemes: for instance, in relation to time in Madras, the Bombay Presidency operated 49 min behind, the Calcutta Presidency opera-ted 21 min in advance, and the Andaman Islands [Port Blair] operated 49 min 51 sec in advance. Goldingham in 1802 established Madras Time as GMT+05.30 h. Madras Time was then nominated to represent 'Indian Mean Time', then an 'unofficial' standard. Madras Time was later chosen as the 'Railway Time', enabling coordination of train timetables throughout India, because other areas followed their own time constructs. For instance, during the International Meri-dian Conference held in Washington D.C. in 1884, India had two distinct time zones: Bombay time and Calcutta time. On January 1, 1906, Indian Standard Time (IST) was established. Nevertheless, the other time zones continued until India's independence in 1947.

Pendulum studies

An exciting experiment Goldingham made was to trial Henry Kater's invariable pendulum. Kater is remembered for his compass and pendulum, which indicate the interconnected areas of geodesy and meteorology. Kater too had a Madras connection. He was born in Bristol in 1777, joined the British Army in 1799, and came to India to assist William Lambton in the Madras Presidency survey. Due to ill-health, Kater returned to England in 1814 and died in London in 1835. He designed and created precision measurements relating to the standardisation of weights and measures. In this context, Kater became interested in metallurgy and metal properties, and thus got interested in pendulums.

Systematic survey of the gravity field of the earth began to receive attention throughout the world following Kater's studies in England. Kater designed, constructed, and applied a convertible compound pendulum for the absolute determination of gravity in London, in 1817.

Kater sent an invariable pendulum, which he had constructed in London in 1820, to Goldingham who tested its swings in Madras in 1821.

Architecture

Goldingham's contributions to architecture have been extensively referred to in Madras Musings in the past. Therefore, I do not intend repeating them. Undeniably his most magnificent contribution to Madras was the design of Banqueting Hall (now Rajaji Hall). The Internet site of Europeana (c/- The Koninklijke Bibliotheek, The Hague, The Netherlands) provides reproductions of at least 16 drawings of floor plans, elevations, and sections of Government House, Madras (alas, now no more) and adjoining buildings made when Goldingham was Madras's Civil Engineer in the 1800s. These holdings are copies prepared for Edward Clive, Governor of Madras (1798–1803), and are at present archived in the British Library (London).

Archaeology & Epigraphy

In a paper entitled Some account of the sculptures at Mahabalipuram; usually called the seven pagodas (Descriptive and historical papers relating to the seven pagodas on the Coromandel Coast), 1869, Mark Carr (Ed.), pages 31-43, published by Government of Madras, printed at Foster Press, Rundall's Road, Vepery, Goldingham remarks about the archaeology of the monolithic rock edifices at Mahabalipuram and comments on the sculptures and inscriptions.

|

|

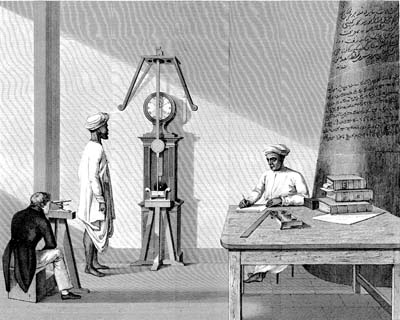

Illustration of the measurement of the acceleration of gravity with an invariable pendulum in Madras by John Goldingham, 1821. JG with a telescope assessing the lags in the swings of Kater's pendulum against the pendulum of the Haswell clock. Thiruvenkatachari (his Second Assistant) is reading the clock; Shrinivasachari (his First Assistant) is jotting notes. (Source: Goldingham J, 1822, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, 112, 127–170).

|

On the architecture of the Mahabalipuram edifices, Goldingham says, "The difference in style in the architecture of these structures, and those on the coast hereabouts… tends to prove that the artists were not (of) this country; and the resemblance to some of the figures and pillars to those in the Elephanta cave, seems to indicate they were from the northward. …" Mark Carr, editor of this volume, inserted a footnote on Goldingham's reference to the 'northward' origin of the Mahabalipuram sculptors, quoting the following short text from James Fergusson (1846, 'On the rock-cut temples of India', Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, 8:30–92): "There is nothing here of which the prototype cannot be traced to the caves of the north. In plan and design they resemble the Hindu series at Ellora, though many of their details (are) as only to be found at Ajunta and Salsette."

While remarking on some inscriptions from the Mahabalipuram relics, Goldingham indicates that they were taken (obviously he means 'taken down') "by himself with much care". The last inscription in the Goldingham paper was taken (down) from the pavement of the choultry near the village and Goldingham remarks: "... very roughly cut, and apparently by different artists from those who cut the former". In the same Mark Carr volume, in the article An account of the sculptures and inscriptions at Mahâmalaipûr; illustrated by plates (pages 44–62), Benjamin Guy Babington clarifies that these rock inscriptions are in modern Telugu character, which indeed they are.

* * *

I began writing this article focussing on Goldingham and his contributions to Madras science. But as I got more and more information, it turned out to be a piece pertaining to the MO in general and other lateral scientific interests of Goldingham, besides including references to other key Madras astronomy names such as Raghoonatachary and Kater.

|