James Anderson M.D., portrait published

by James Anderson, LL.D., in The

Bee (1792, vol. 9) [frontispiece].

|

Cover page of a documented work of

James Anderson.

|

James Anderson (1739-1809), holding an M.D. from the University of Edinburgh, came to Madras from Scotland in 1761. He was appointed an Assistant Surgeon with the English East India Company in Fort St. George in 1765. He was promoted as full Surgeon in 1786 and, later, became the Physician-General. The plant Andersonia1 (Meliaceae, the mahogany family) celebrates his contributions to Indian botany.

Those interested in Anderson of Madras need to know that there was another James Anderson living concurrently, but in Scotland. This Anderson is referred to as ‘James Anderson LL.D.’ so as to distinguish him from the Madras Anderson who grew up with James Anderson, LL.D. (1739-1808). They studied in the same school in Hermiston (Scotland), and were close friends. They may even have been distantly related.

James Anderson, LL.D., also known as ‘James Anderson of Hermiston’, was equally of brilliant mind, who indulged in several scientific and knowledge-advancement activities. He designed and developed a two-horse plough, which later came to be known as the ‘Scotch plough’. He edited and published a popular weekly, the Bee (The Literary Weekly Intelligencer), which included several articles and notes by the Madras Anderson.

In an earlier issue of the Madras Musings (December 16, 2010) I wrote on the nopalry in Saidapet where the dye-yielding cochineal insect was cultured and Anderson Gardens in Nungambakkam where Bourbon cotton, mulberry, indigo, and several other plants, such as chaya ver (Oldenlandia umbellata, Rubiaceae) of economic relevance, were grown. Both were set up on the sole initiative of James Anderson. As I have written about his botanical experiments, I focus on his other activities in Madras in this article.

Deposition on death of Lord Pigot

Anderson was one of those who in 1777 deposed before the King’s Coroner of Madras George Andrew Ram following the mysterious death of Lord George Pigot (1719-1777) while in confinement in Madras after a coup. At that time, the Chief Surgeon was Gilbert Pasley; he was also the doctor attending on Lord Pigot. Thomas Davis and William Mallet (Assistant Surgeons) also reported to Pasley. The full text of Anderson's deposition before the coroner are available in the Original papers with an authentic state of the proofs and proceedings before the Coroner’s inquest assembled at Madras, upon the death of Lord Pigot, on the 11th day of May 1777 (published by T. Cadell, London, 1778).

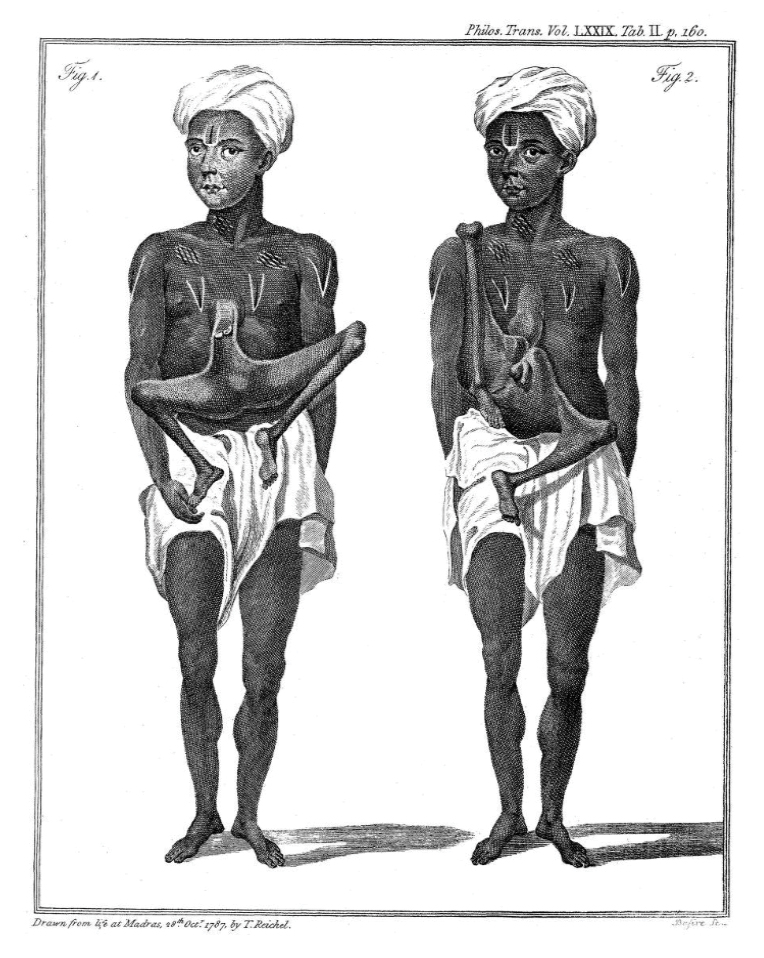

Report on a parasitic twin

Thirteen-year-old Peruntaloo (bearing

a parasitic twin) from a village near

Masulipatnam. Drawing by Baron T.

Reichel, a visitor to Madras from Germany

in 1790s.

Conjoined twins are rare. We know today that a parasitic twin (also known as ‘asymmetrical twins’) is the result of the processes that produce vanishing twins. Parasitic twins occur when a twin embryo begins developing in utero, but does not fully separate, and one embryo maintains dominant development at the expense of the other. Unlike conjoined twins, one ceases development during gestation and is vestigial to a mostly fully formed, otherwise healthy individual of the twin. The undeveloped twin remains parasitic, rather than conjoined, because it is incompletely formed or wholly dependent on the body functions of the complete foetus. The ‘apparently’ normal independent twin is referred to as the autosite.

Details of this parasitic twin, unfortunately termed a ‘monster’ in those days, are to be found in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, 1809. The two brief letters to Sir Joseph Banks, who was the editor of the journal, were from Baron T Reichl and Anderson. The Baron Reichl and the Baroness were travelling via Madras during Anderson’s time. The Baron was a talented artist, who had drawn many of the birds of southern India during his travels, and had also published a book titled Life at Madras.

Smoking ‘stramonium’ for asthma

Datura.

Indian physicians have been recommending smoking of parts of Datura (a nightshade species related to the tomato and potato, in a broad sense) to their patients to get relief from asthma. The tropane alkaloids of this plant, similar to the contents of its close relatives Atropa and Hyoscyamus, get released when smoked and they can relax and dilate the inflamed lung tissue. Although Indian physicians did not know the chemistry of Datura, they knew of the potential of this plant that, when smoked, offered relief to their patients from torturing asthmatic attacks. Datura ferox is an Indian species, but having exhausted its supply for medicinal use, D. stramonium was resorted to for comfort from asthmatic paroxysms. Datura stramonium is a plant that has high toxic potential and when used needs to be used at measured levels.

Anderson seems to have discussed with Major General William Gent of the Madras Army about the use of stramonium for relief from asthma. Details of the discussion are to be found in a letter by an English physician (Dr Sims), who practised in Guildford Street in 1802. The relevant section reads:

“Sometime in the year 1802, I received from General Gent a remedy that he had not long before brought from Madras, which, the General informed me, was used there as a specific for relieving the paroxysm of asthma, and that it was prepared from the roots of the wild purple-flower thorn apple (Datura ferox). The roots had been cut into slips as soon as gathered, dried in the shade, and then beat into fibres resembling coarse hemp. The mode of using it was by smoking it in a pipe at the time of paroxysm, either by itself or mixed with tobacco, according as the patients were previously addicted to smoking or not. General Gent procured this remedy from Dr Anderson, Physician General at Madras, who both recommended it and, I believe, used it himself.”

Anderson deserves acknowledgement here for introducing a ‘useful’ plant and its active principles in Britain and in continental Europe, based on his learning achieved from Indian physicians. Datura stramonium was enthusiastically adopted by asthma patients and their doctors; references exist stating in 1819 that D. stramonium was “cultivated in a few English gardens”. The tropane alkaloids of Datura need to be used with extreme caution; unfortunately that knowledge from Indian physicians was not transmitted to Europe. The immediate relief provided by smoking of Datura blinded many and eventually many succumbed to the toxicity of this aggressive plant. William Gent was one who died because of constant and unregulated smoking of D. stramonium.

First health-quarantine event in India

When the French occupied Egypt in 1802, troops from the Indian Army were sent to join the British forces in pushing out the French. But by the time the Indian battalions arrived in Egypt, the French had surrendered. The Indian Army personnel returned to India from plague-infested, British-held Egypt. On hearing about the plague in Egypt, the Madras Governor, Lord (Edward) Clive, urged the District Collectors to implement every possible precaution to prevent the spread of plague: any ship from the Red Sea was not to enter the harbour, except under dire circumstances. The ships – Candidate, Anna and Amelia, Cecilia, Shaw Byrangue, Earl of Mornington and Griffin – were denied entry in Madras. Because of a lack of organised quarantine in Madras, the boats were directed to Ennore, which was designated the ‘Quarantine Point’ with a Major Orr appointed as the Quarantine Officer. On arrival in Ennore, the Captains wrote to the authorities that “… nothing like the plague, or any kind of contagious fevers of a pestilential nature … existed on board.” Lord Clive directed the Madras Medical Board (MMB) to verify this assertion. Andrew Berry, the Head Surgeon and a nephew of Anderson, went to Ennore Quarantine Point (EQP) and reported that Orr had requested him to examine the occupants of two of the five boats. Berry found none sick among them, and none had been ill even for one day during the journey.

This report is unusual, because each boat carried 100-300 soldiers plus crew members on a month-long journey from Cairo to Madras, and the likelihood that all passengers were ‘unusually’ healthy, and that only one person had died en route due to sea scurvy, seemed improbable. Nevertheless, Anderson, then the Physician General of Madras, confirmed Berry’s report after going to EQP. Anderson boarded the ships and examined the crew and the soldiers, store lascars and artificers, engineers, commissioners of provisions and public and private followers. These examinations were completed in a day and, therefore, must have been ‘cursory’.

Anderson reported to Lord Clive that he wished that the rest of the troops were in as perfect a state of health as those he examined. Anderson also reported that some of the crew members were unhealthy and were in hospital. He made a list of those individuals and the ailments they suffered. However, this document was ‘lost’ before it reached Fort St George. But not much attention was paid to the loss.

Both Anderson and Berry recommended that the EQP be disbanded: the facility was on low, flat, clayey soil, which during heavy rains would become unwholesome, the Cairo-Madras journey lasted 54 days and was long enough to offer protection against (any) disease, the quarantine process was at best ‘a formality’ and at worst ‘an expensive encumbrance’ to the government, and because he considered that this plague was transmitted through soiled linen, blankets and clothing and also because all such materials had been either repeatedly washed or burnt, Anderson saw no possible nucleus for the Egyptian infection. Following this recommendation and in less than a fortnight after the threat of plague first acknowledged by the Madras Government, the Government suspended the EQP. In four days, the Governor-in-Council passed the resolution to relieve the troops and transports from EQP. The importance of this event, although not of any profound significance, is that this is the first recorded formal seaport quarantine event in the whole of India.

Promotion of vaccination in Madras Presidency

In February I804, Anderson, then the Physician General and President of the Medical Board, was keen on promoting vaccination to fight against the deadly smallpox in the Madras Presidency. A supply of the lymph was received from Vienna through Bombay in early 1799. George Pearson of London had sent Jean de Carro in Vienna a supply of lymph upon threats of infection. de Carro vaccinated successfully with this supply, and in turn sent some of the lymph to Thomas Bruce, Earl of Elgin (1766-I84I), the collector of the Elgin marbles, who was then British ambassador at Constantinople. He, after vaccinating his own son, transmitted some of the lymph to Bombay, which enabled the rapid spread of the practice of vaccination in India.

The new method was at first opposed by Indians, but their objections were in part overcome by a ‘pious fraud’. Ellis, the Civilian of Thirukkural fame, composed a short Sanskrit poem on the subject of vaccination. The poem was inscribed on an old paper, and was said to have been “found”. Stress was laid upon the fact that the benefit was to be derived from the sacred cow. Public vaccinators were soon appointed for the different Presidencies. There were at first Superintendents General of Vaccination, under whom were Civil Surgeons at certain stations, with a special allowance for their services, and each with a staff of one or two native vaccinators.

Conclusion

James Anderson contributed to the botany and medicine of the Coromandel substantially. His major contributions were in establishing a nopalry and a mulberry garden. He paid considerable attention to other plants of commercial importance, such as sugarcane, coffee, American cotton and European apple. In a letter to Robert Brooks (Governor of St. Helena, West Indies), Anderson stated:

“What benefits would result to society, if men of letters would in general turn their attention towards useful pursuits! How much might the lot of mankind be ameliorated in a few centuries of such pursuits! Europe, Asia, Africa and America would thus contribute its share to the general improvement. And every country on the globe would be bettered for it. The mention of one plant alone, introduced into Europe from America, the potato, is enough to awaken the attention of every person, whose soul can feel the expansive glow of beneficient affections, and make them look up with gratitude to those, who by attentions of this fort, have proved the best friends of mankind.”

The preceding text speaks eloquently of his excitement in securing benefits from natural materials (= resources) for the people. Nonetheless, an underpinning urge to improve Britain’s economy by exporting knowledge and material resources of India to Britain always laced the efforts of Anderson.

A eulogy referring to his life and career is available in the Scots Magazine and Edinburgh Literary Miscellany (March 1810). The eulogy refers to Anderson in words from Cicero: ‘Natura ipsa valere, et mentus viribus excitari, et quasi quodam divino spiritu inflari’.

To me, Anderson stands far above many of his contemporaries; he outshines many of them by his tireless effort and thirst for knowledge. Not surprising that on his death in Madras in 1809, his pall bearers were Sir Thomas Strange (the Chief Justice), Sir B Sullivan, the three members of the Madras Council, the Commander-in-Chief, and his nephew Andrew Berry (the chief mourner). A meeting of the Medical Officers of the Presidency later resolved that a suitable memorial be erected in his honour. A sum of 1000 guineas was raised through generous public subscription and contributions from the Medical Officers of the Coromandel. And there soon came up the elegant life-size marble statue by Francis Leggett Chantrey that is in St George’s Cathedral today.

1 This name is at present invalid; the current name of the plant is Aphanamixis. I would caution readers that another plant named Andersonia (Ericaceae, the heather family) exists, but this is not a reference to James Anderson.

|