|

Perspective in art is something I began unravelling well before I even knew the word ‘perspective’.

I have drawn pictures ever since I can remember. Even in those days, my parents – who were artistic-minded themselves – recognised that the quality of my drawings was better than those of other children of my age known to us. The school teachers too saw that I had artistic potential.

During my boyhood (1940s), drawing classes were compulsory in schools up to the secondary level. When I was in the Fifth Standard, we were taught how to draw a rectangular slab. Here, lines AB, DC and HG are equal in length and parallel to one another. So is the case with lines AD, EH and BC. However, the electric commuter trains of Madras taught me that – unlike in the drawing – parallel lines in a real object seen at an angle will not appear parallel in a drawing and their lengths would seldom be equal in the drawing, even if they were so in the real object. How did I learn this from electric trains?

When I was in secondary school, in the mid-1940s, I became totally immersed in drawing steam road-rollers, fire engines, those gawky World War II planes and, above all, steam-engine trains. Many boys of my age group at that time too were interested in them. But the difference was that I could draw – somewhat clumsily, but, of course, far better than my classmates.

I grew up in Madurai. My paternal grandparents lived in Madras. I spent many summer and Christmas vacations with them. From their house in Thirumalai Pillai Road, T’ Nagar, we travelled to the heart of the city using the commuter electric trains. I loved these trains, not so much from an artistic point of view but rather as something representing power, speed and action. I immensely enjoyed hearing the saxophone roar of their traction motors, as the trains accelerated, and the bugle calls of their powerful horns. All these fascinated me.

Our family always went from Madurai to Madras by steam-engine train, which would invariably reach Tambaram early in the morning. This is where the electric commuter trains started their day. Our steam-engine train would leave Tambaram only to stop at the terminus, Egmore. The electric trains, of course, stopped at each and every station in between. The electric train would start from one of these stations, and with high acceleration would soon catch up with our speeding, smoke-belching express train and begin to overtake it, only to decelerate suddenly as it apporached the next commuter station, while our express train pressed on. The electric train going in the opposite direction would appear and disappear like a flash. A unit of the electric train had only three carriages, the traction motor being located in the centre of the middle carriage. During peak hours, they coupled two units together.

Back in Madurai, I learnt that none of my classmates had ever been to Madras – they simply called it pattanam (the city) in those days. They had not heard of electric trains. I shared my knowledge about the electric train with them, talking about its power, the sound it made, speed, horn and all these through the current it drew from a wire suspended above. I tried to draw a picture of an electric train – the drawing did not show what I wanted to convey.

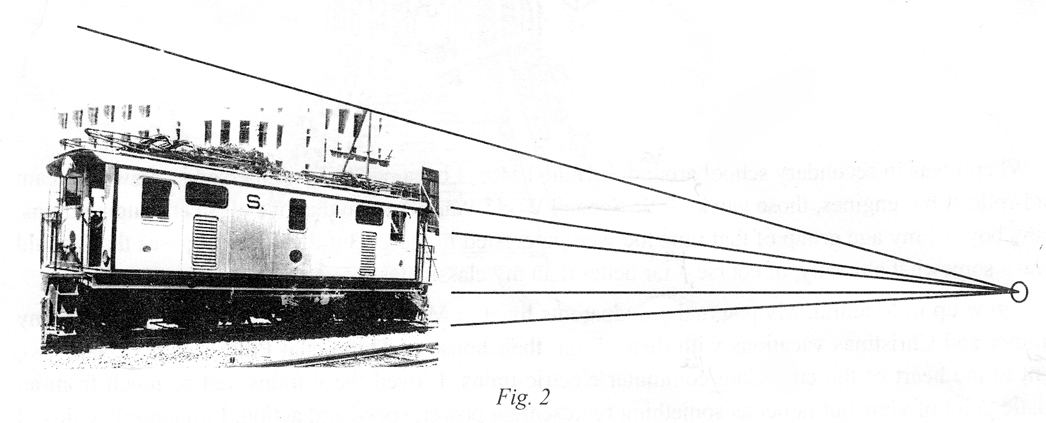

During my next summer vacation, I saw with my uncle, Babu, a photograph of a single electric traction engine designed to pull a large number of goods wagons. While in Madras, I studied this photograph, I stuck it gently on a foolscap sheet and extrapolated the traction line, the top and the bottom lines of the engine, and the line of the rail. To my utter astonishment all these lines merged into a single point. I had only completed my Sixth Standard (1st Form) and I had unwittingly, and partly out of curiosity, opened – not Pandora’s box – but the magic box of perspective.

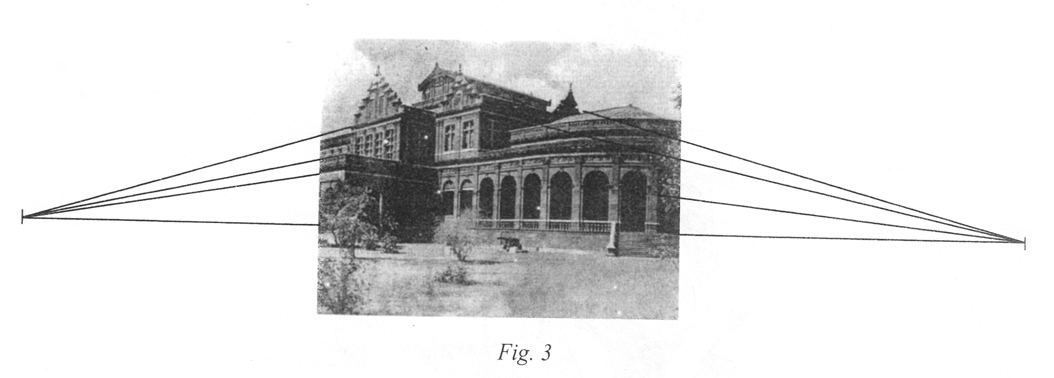

From this humble discovery, I figured out that what applies to a severely simple object like a commuter train would apply equally well for complex buildings. I pulled out photographs of buildings and lightly stuck them on to foolscap sheets and extrapolated converging lines that were not parallel in the photographs but which were parallel in the actual buildings. It was sheer delight for me to find two vanishing points – one each for two sets of lines that were perpendicular to each other in the ‘real building’. This exercise also reaffirmed in my mind that an object in a perspective drawing usually has two or more vanishing points.

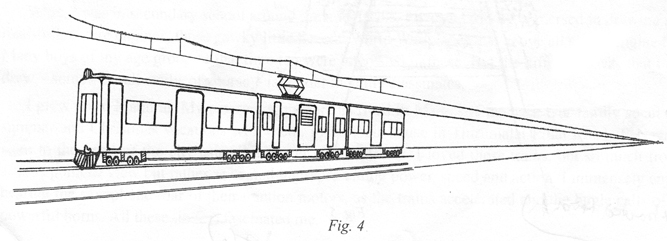

A couple of years later, when we were again in Madras, I saw a new photograph of an electric train taken at an angle. I extrapolated the power line, the top line, the window lines and the bottom line to the vanishing point. The gap between the end of the last carriage and the vanishing point was not at all that much. A rudimentary ink drawing of a unit of a an electric train that I did years later shows this aspect.

If the train had another unit of three carriages, that too would fit in without crossing the vanishing point, would it not? What about 100 units next to one another? How about 1000 units? It seemed irrational to expect 1000 units to fit in. It really bothered me. I had no answer.

One day, when I was in Seventh Standard, our family went by car on a highway. The railway level-crossing gate was closed and a steam-engine train stood still nearby. I got out of the car, climbed over the gate and stood in the middle of the rails and looked at the steam-engine. It was a forbidding sight. At the same time, for a little boy it was also a new vision. I had never seen a railway engine’s face until then. By this time, I knew that the tracks woujld ‘appear’ to broaden towards me. The carriages stood on a curved track. I was able to see some of the rectanglular (lengthwise) rear carriages, which did not quite appear rectangular.

(To be continued)

Manohar Devadoss , that brilliant near-blind artist who produces meticulous drawings of people and places, tells you in this series how he began drawing and continued to do so even as his sight deteriorated. These excerpts are from his recently released book, From an Artist's Perspective , which tells a human story as well as offers advice to all who draw

|