|

(Continued from last fortnight)

When I was seven we lived in Kottaiyur (in Chettinad), my father had a framed picture of Mahatma Gandhi. My parents told visitors that the speciality of this portrait was that Gandhi looked at the viewer with smiling benevolent eyes, wherever the viewer stood, I stood to stare at the portrait from one side and then walked to the other side of the room. Gandhi’s eyes followed me.

An aunt of mine had a framed sepia portrait of Jesus Christ with piercing dark eyes, looking at the viewer. My aunt was an affectionate but fanatically religious person. She warned us children to behave properly even when we were alone, as Christ watched us always. She claimed that the portrait represented what she said.

She would make one of us stand on one side of the picture and another child at the other end of the room. She would ask the first child as to whom Christ was looking at. The child would answer, “Me.” She would ask the other child the same question and get the same reply. Then my aunt would go on to say, “See, He is looking at you both at the same time, though you are on the opposite sides of the room. Please know that He watches you wherever you are.”

Surprisingly, the frontal view of the steam engine train that I had drawn*, gave me the insight – a few years later – something that should have been obvious to people which often was not. If a framed drawing of a frontal view of a railway train is displayed it would seem to hurtle directly towards the viewer, wherever the person stood. It would seem that the person stood between the rails and nowhere else.

What applies to a gross object like a railway engine, naturally applies equally well to the fine eyes of Gandhi and Christ too. Actually, along with the eyes, the face, the body, in fact, the entire picture has a single orientation.

At Kottaiyur, if Gandhi in the picture saw one person standing in one place, he would necessarily see every person standing around the portrait. So, there was nothing special, as my parents thought. If Gandhi saw one person standing in one place and did not see another standing in a different place, then, that would have been a miracle!

So, in an old Tamil movie full of twists and turns, the super-matinee idol of yesteryear, M.G. Ramachandran, in a specific situation looked into the movie camera and sang in Tamil, in T.M. Soundararajan’s playback voice, “I am the son of your household, a truth known to all....” It seemed to every movie-goer that he sang it looking at each viewer directly. Many hearts melted.

* * *

Sometime during my secondary school years, Nawab Rajamanickam’s all-male drama troupe camped in Madurai for many months and presented a series of popular plays, including one on Jesus Christ. Nawab created some stunning effects for those times. However, a man singing and dancing as the voluptuous Salome was a bit unconvincing. The troupe also presented impressive, elaborate settings. When there was a scene change, a curtain would drop down and a comedian would come to the fore – to the narrow strip between the curtain and the edge of the stage. He would do his bit to keep the audience entertained, even as furious activities would take place behind the curtain for the scene change.

The curtain, I remember, had a frontal view of a village street in perspective with two lines of houses, one line each on either side of the street. Rather than watching the comedian’s caper, I would study the details of the street behind him. I could figure out that the vanishing point was at the centre and the eye level of this point – if my memory is right – was below the comedian’s shoulder level. The curtain, of course, gave an illusion of space behind the ‘street performer’.

* * *

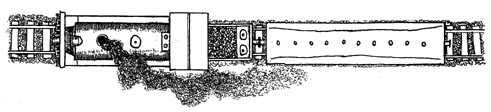

One day, standing above it, I watched an engine go by right under my nose – with just one blast of hot air hitting my face. I became quite excited with a simple idea that struck me. When I reached home, I made a drawing of an engine and a carriage, as seen from the sketch below.

At that time, I did not know that I had done a simple ‘plan view’, not unlike that of a routine engineering drawing but without measurements. I had no idea that in later life I would be involved in designing and creating countless engineering drawings. The following morning in school, I showed my sketch to my classmates. They looked blank. When I told them that it was a railway engine and enthusiastically pointed out the chimney, the roof of the driver’s cabin and the like, my fellow students remained unimpressed and unconvinced. I explained to them that how an object would be represented in a drawing depended upon the position from which it was looked at. I told them that a gramophone record seen sideways would appear like a line. So a straight line could represent a gramophone record too. This example was a strategic error on my part. While verbally describing an aspect which was not readily understood by listeners, you should never choose an example which would be even more incomprehensible.

My classmates burst out laughing. All this took place while the teacher was conducting a class. One of the students snatched the drawing from me, took it straight to the teacher and asked him what it was. The teacher did not have the foggiest idea. Another student told the teacher that I had drawn a straight line and called it a gramophone record. Yet another said that I claimed that what I had drawn was a railway engine. Smiling with amusement, the teacher observed that I said such things because I was loony. The teacher had confirmed what the students had suspected all along. And I suffered this nickname for a year or so.

* * *

I was born in Goripalayam in Madurai in 1936. In the late 1930s, hardly any plane at all flew over this town. However, in the early 1940s, during World War II, an occasional plane, or even a small group of them, would fly over Madurai. At such times, men, women and children would rush out of their houses, pointing at the sky and shout excitedly, “Aeroplane, aeroplane.”

In the early 1940s, while in my first years in school, we heard one morning an ear-splitting roar, liberally sprinkled with equally loud sputtering sounds. All the children and teachers rushed out of the ‘open’ classrooms to see what was up. Suddenly and briefly, we saw a plane flying very low. It was obviously in trouble. It seemed that the plane might even crash somewhere nearby. For the first time we children saw a plane flying so very low. Some of them claimed that the plane flew so low that it touched the top of a tree which was not far away and was in full view.

It seemed so, yet somehow I knew that though the plane was not high in the sky, it did fly at a level distinctly higher than that of the tree top. Besides, I sort of felt – even ‘knew’ – that the plane was farther away from the tree. I could see that the plane did not touch the tree top because the third dimension was in play although, of course, at that time I had never heard of ‘three dimension’ or 3D or stereo vision.

* * *

By 1975, I lost the vision in my right eye and became a ‘one-eyed Jack’, so to speak. Even with one eye, a person can see objects that are close somewhat three-dimensionally. If you see an object at 15 cm and another at 20 cm, then the lens within the eye will increase or decrease its power accordingly. So, you would have a stereo effect somewhat vaguely. But I could not even enjoy this aspect, because due to a cataract the biological lens in my left eye was removed in the early 1980s, without a clear plastic intraocular lens. Since then I have been seeing the world – to the extent I could see – only two-dimensionally. It seems to me that it is not at all inappropriate for such a person to write about perspective drawings which are two-dimensional.

* * *

A temple with its tower at the foot of a hill is not an uncommon sight in Tamil Nadu. Alagar Temple, north of Madurai, with its gopuram (tower), for instance, is very near the base of the forested Alagar Hill, as you can see from my picture.

Again, Murugan Temple, south of Madurai, has its tower north of the monolithic hillock, Thirupparamkunram. Many long mandapams (spacious halls) lead you to the sanctum which is carved right into the virgin rock of the hillock. From the point of view of perspective, you can make very interesting observations relating to the pair – a temple tower and its backdrop of a hill.

When I was a schoolboy, well before nondescript, characterless, shanty houses cropped up here and there north of the hill, you could have a clear unobstructed view of this hill and the relatively smaller Muruga Temple tower from half-a-kilometre away or more. As you approach the temple, the image of both grew larger, but that of the tower grew more significantly so that, after a stage, its image would be higher than that of the hill. Now, at close range, strangely – perhaps not so strangely – you would perceive the hill to be smaller.

* * *

A south-facing street house in Goods Shed Street in Madurai had a spiral staircase right on the pavement, leading directly to the first floor. Spiral staircases are used as great ‘space savers’, but they do have a beauty of their own. As a schoolboy, whenever I happened to go by this house, I chose to walk on the opposite pavement so that I could have an overall view of it and its spiral stairway and enjoy its simple beauty.

One day, on a whim, I began running up and down the spiral steps as fast as I could. When I ran up, I suddenly saw a woman at the top of the staircase looking down at me sternly. I stopped short. She advised me not to run madly down the spiral. My head could spin and if I tripped, I might badly hurt myself in the narrow, sharply twisting stairway. She was not really angry with me for my intrusion into her space, she was only concerned that I should not injure myself because of my rashness. That was the typical Madurai of my boyhood.

At that time, of course, I had not thought of the problems posed by the perspective of an open spiral staircase. (I later did and drew a picture of the house.)

(To be concluded)

|