Alfred Tampoe, the Civilian and magistrate

|

In 1911, when the Collector of Tinnevelly, Robert Ashe, was assassinated in his railway compartment at Maniyachi Station, Alfred Tampoe was appointed to try, under the provisions of the Indian equivalent to the English Defence of the Realm Act, the conspiracy case which arose out of the murder. He committed the accused to trial by the High Court, which sentenced the leader of the conspiracy, Nilakanta Brahmachari, to imprisonment.

During his imprisonment, Brahmachari jointly with Tampoe wrote a detailed history of the underground political movement in South India up to the date of the assassination of the Collector of Tinnevelly. This treatise received the full approval of the Government, and remained a standard work on the subject. In recognition of this contribution, a remission of his sentence was granted.

During the course of their joint literary effort in the prison cell, magistrate and prisoner became friends. It was a friendship that was to last over half a century.

While serving his sentence, Brahmachari subjected his outlook on life, and on the world, to a critical examination, which convinced him that the use of physical force, even if effective at the particular time, was unworthy of the dignity of human personality. When he was freed, the former political anarchist became a sadhu, Sri Sadguru Omkar of the Nandi Hills. The Sadguru was to later write:

'It must be unique for two persons who first met as accused and magistrate to become fast and intimate friends and continue to remain so for more than 50 years with the greatest mutual regard possible between two human beings. Such was the contact between me and Alfred Tampoe.

I was arrested at Calcutta in the first week of July 1911 in connection with the Ashe Murder Case, otherwise known as Tinnevelly Conspiracy Case, and brought to Tinnevelly and, with a large police escort, taken before Mr. Tampoe, who was then Headquarters Assistant Collector. I was brought to his bungalow on July 10, 1911. The European Superintendent of Police who was in charge of the escort suggested that I be taken on foot to the Palamcotta District Jail, a distance of one mile from the bungalow, evidently with a view to parading me through the streets of the town to impress on the people the might of the British Government and also to humiliate me. I lost my temper at this further humiliation and spoke some angry and very uncomplimentary words about the Superintendent, the British Government and its menials, the Collector and others who were present. The reaction of Mr. Tampoe to my outburst was characteristic. He said, "Calm yourself, Nilakanta (My name was Nilakanta Brahmachari and I was the first accused among 14 charged). You have come all the way from Calcutta in a train with a police escort for four days without sleep. First wash yourself and have a cup of tea."

Then he called his butler to bring me a bucket of water and after I had washed, he gave me a cup of tea and then a cigarette from his pocket and lighted it himself. (I was a heavy smoker in those days.) Then he ordered that I be taken to the jail in a jutka with only three policemen as escort. This arrangement to come to the court from the jail and return to the jail in a jutka continued during the whole course of the trial in the lower court (his court) for nearly two months.

But in his order committing us all to trial before a special tribunal of three judges of the Madras High Court appointed for the purpose, he did not show me any favour. After recording and analysing the evidence of nearly two hundred witnesses, he, as an impartial judicial officer, saddled me with the full weight of all the offences charged. One sentence in his committal order, which he probably meant as a compliment, worked much to my disadvantage in the High Court. That was, "He is the only man among the whole lot."

I used to meet him every day in his room in the bungalow which was his court, as I was kept separate from the rest of the prisoners, and have tea and cigarettes with him and discuss all sorts of things. I was 22 years old at the time and he was about 29 and still not married. For an Indian officer, though of I.C.S. cadre, he was bold, independent and just. When once I asked him as to what he thought would happen to me, he said very casually that I might get 10 years. I did get seven years after a protracted trial in the Madras High Court.

After my release from jail in 1919, I contacted him and we became dear and devoted friends. He sometimes called himself my sishya, though I never accepted this position. We met often during those years, stayed together at various places, ate together and he visited my ashram on the hill-top with his son. I have also stayed with him in the Principal's room in Kavali College.'

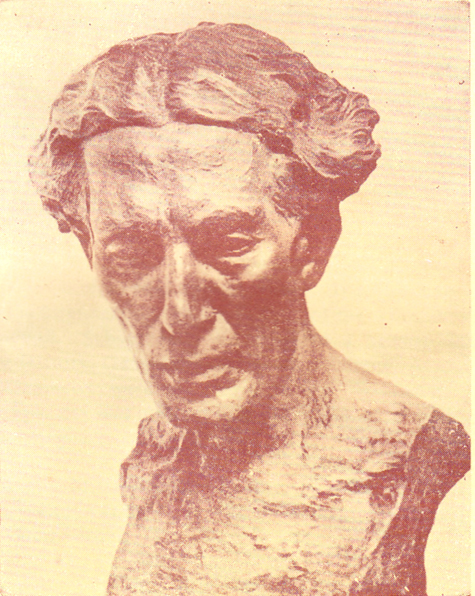

Alfred McGowan Coomarasamy Tampoe by his close friend Debi Prasad Roy Chowdhury.

|

The sporting Civilian who became a don

Alfred McGowan Coomarasamy Tampoe was born on June 25, 1881 in Jaffna, Ceylon. His father, T.M. Tampoe, a solicitor, was a Hindu who became a Christian. The rest of the family were Hindus, whose family temple was dedicated to Lord Coomarasamy.

After attending a village school and a Mission school, Alfred Tampoe became a boarder at St. Thomas' College, Colombo, which was modelled on the lines of an English Public School. No vernacular language was either taught or officially employed at the College. Furthermore, its use was forbidden to all students during school hours, and to all boarders throughout all hours in the College premises. Latin was compulsory.

Obtaining several double promotions, he reached the top class of the College at the age of 16 and was considered by his parents to be fit for Cambridge University. But on arrival at Cambridge, he was advised to go back to school in spite of his academic qualifications. Being already in England, he joined an old English Grammar School, one of the famous Alleyn schools, at Stevenage, Hertfordshire. He gained his 'Cricket Colours' at Stevenage, and was even chosen to play for Hertfordshire County in his first year in Stevenage.

At Cambridge, he took his degree in Mathematics, and then moved to Frankfurt University, Germany. While a student there, he appeared for the ICS open competition examination in 1904 in London and, as he expressed it, "much to my surprise", he passed through.

He was assigned to the Madras Presidency and joined as Assistant Collector at Masulipatnam. His first assignment was as Head Assistant Collector, Narasapur, in the then Kistna District. He held the usual routine posts, but it is worthy of mention that his services were lent successively to the PWD to study and report on the discharge of water for irrigation purposes through sluices and canals in certain parts of the Kistna Delta, and then to the Department of Agriculture to report on certain agricultural practices connected with paddy cultivation in the Western Godavari Delta. The highlight of his tenure as Head Assistant Collector, Tinnevelly District, is related below.

* * *

During his entire Government service, Tampoe spent all his furloughs at Cambridge where the University gave him an academic appointment during every visit.

On his premature resignation from the Indian Civil Service, he settled in Cambridge where he held the post of Reader in Dravidian Languages.

During World War II, he was an adviser in the Citizens' Advice Bureau headed by John Hilton, Professor of Industrial Economics, at Cambridge. He was later appointed a member of the Panel for Oriental Languages of London University, and then was a First Grade Officer on the staff of the BBC's Eastern Service.

His health being affected by the climate, he resigned from all these positions to return to India where he was asked by the public-spirited founders of Kavali College to join a pioneer venture in academic education, "an effort with a definite degree of idealism behind it," as C.D. Deshmukh described it. Tampoe, during retirement, insisted that his four-year association with the college was perhaps the most valuable opportunity to come his way during his life.

* * *

His fondness for sport received a severe setback early in his second year at Cambridge, when an injury to his knee while playing hockey led to his remaining out of active participation in any sport for four years and may have cost him a Blue. But he continued to ride.

Always fond of horses, he rode with the famous Yellow Uhlans, during his stay in Germany. He also attended the British Army Riding School in Woolwich.

In those spacious days when the European members of the superior services in India believed not only in hard work but also in plenty of exercise in the open air, nearly every District Headquarters boasted of a 'Hunt', generally with a very miscellaneous collection of hounds with which, once a month, they hunted either jackal or an occasional fox. Tampoe regularly rode in these Hunts.

While in the Districts, he actively participated in District Cricket, Tennis and Hockey as well as, in the case of Rajahmundry, where there was a polo ground, local Polo. He was a member of the District teams wherever he served. He attributed his health and mental vigour throughout his long life to his participation in sport.

|