|

In the late 1970s, my daughter Suja and I enjoyed the hospitality of the Appasamys at Kodaikanal each summer. Paul, their son, and I would go on mini on-the-spot sketching expeditions. In 1978, early one morning, each of us did a sketch of the boat house with its reflection in the very still waters of the lake. That evening, we reflected upon this subject. Paul said that the reflection of the boat house was identical to the real one, only it was upside down. I told Paul that there were many subtle differences between an object and its reflection in a piece of artwork. I shared with him my own ‘knowledge’ and then went on to talk about other aspects relating to perspective and architecture. Paul, who was at the time a student of the School of Architecture of Madras University, could grasp immediately what I was trying to convey. It was he who first suggested that I should record my learning processes and insights into perspective and publish the collected material as a book. I talked about this with Mahema, who also felt that a book from my perspective was an excellent idea. It has taken me three decades to eventually do what my cousin suggested and my wife recommended.

I reproduce here, my on-the-spot ink drawing of the boat house at Kodaikanal.

* * *

Among the finest entities still existent within the Thirumalai Nayak Mahal in Madurai is the Nataka Sala. The squat pillars support a complex of foliated arches, with ornate entablatures, high corridors, and windows topped by an elaborate arched roof 70 feet above the floor.

From the mid-1980s, I entertained the idea of capturing a view of this hall in ink. But I felt intimidated. The structure of the hall was complex, my eyesight was poor even at the time, and the level of illumination within was low. However, in 2002, when Mahema saw the hall from her wheelchair, she felt strongly that inclusion of a drawing of this hall would enrich My Madurai, the book I was working on at the time. So, I visited this hall many times and pored over photographs taken especially for me, from different angles by Jayantha from Aravind Eye Hospital. Those were to help me three-dimensionally ‘grasp’ the structure. I chose what I thought was the best angle for my artwork. Jayanth carefully made dark ink lines on a ‘paper enlargement’ of the chosen photograph. This enabled me to see the structure. I extended the angular lines to determine the vanishing point. To my utter astonishment, the lines did NOT converge to a single point. Besides, the repeating patterns were not in alignment. The reason for this anomaly suddenly flashed across my mind.

If the hall is still standing today, it is perhaps largely because of the vision of one man, Napier, the Governor of Madras in the latter part of the 19th Century. He provided the impetus, skilled man-power and the funds for extensive renovation work, which in turn was executed under the leadership of Blackburne, the then Collector of Madurai. Due to the weight of the arched roof, the ornate walls above the supporting pillars began inching irregularly outwards. In order to arrest the walls from moving further, horizontal iron stay rods were periodically provided. From the point of view of perspective, the hall as a result continues to have imperceptible imperfections. But my drawing follows the laws of perspective and eliminates the stay rods.

* * *

In early 1958, when I was 21, I moved from the ancient temple town of Madurai to live in the relatively modern metropolis of Madras. At that time, though I was not very religious, I liked attending services at the Wesley Church at Egmore with a new-found British friend, Ken Wade, or my cousin, Damayanthi. I enjoyed the majestic sounds of the pipe organ there, played by a cousin, Ebby, and the harmonious singing by the choir and the congregation. I enjoyed even the sermons by the learned British pastor. Above all, I enjoyed the ambience and the elegant beauty of the brick-and-mortar church. Four decades later, I decided to create an ink drawing of this edifice.

I chose what I considered the best angle to capture the elegance of the church in ink. Unfortunately, however, at the chosen angle, I was too close to the building. I could not move backwards because the parsonage was at my back. Were I to capture a two dimensional image of the church at such close quarters, a certain level of distortion would have crept in. I used a simple but effective method to minimise the proximity problem thus:

I used the northeast corner wall junction of the church as the reference vertical line (Z axis). I moved the vanishing points farther for both X and Y axes. In the drawing below, point O on X axis is the true vanishing point, while point P is the chosen one. Similarly, Q is the real vanishing point while R is the chosen one on the Y axis. I kept all the relevant vertical lines where they really belonged. The horizontal lines of the real building that were at higher levels would have had steep inclines, had I used the authentic vanishing points O and Q. But as I used the ‘doctored’ points P and R which are farther, the incline of the top lines are far less steep, thus softening the distortion due to the closeness.

* * *

When my friend Suresh Krishna became the Sheriff of Madras in 1990/91, he initiated some renovation of the impressive Victoria Public Hall (VPH), a heritage building which was in a state of neglect. At this time, I decided to make a set of drawing, featuring this noble edifice.

One of the views that I chose for an ink drawing posed the same problem as that of Wesley Church – only, in this case, the situation was worse, as V.H.P was far larger and taller. In the very angular view, at close quarters the vanishing point is relatively close. The roof line would have been rather steep, its left end becoming dominant, making the tall, tile-roofed tower appear less significant. In order to minimise this unsatisfactory visual aspect posed by a ‘true’ perspective drawing, I planned with impunity a carefully calculated error in its perspective. I divided the building into three blocks. I allowed the first, right side block with the tower, to retain its natural vanishing point (A), moved the vanishing point of the middle block a bit farther (B), and that of the third block (left) still farther (C). On account of this, my drawing had three discrete vanishing points instead of a single one. By this, the tower maintained its integrity and dominance, while the roof at the left end was kept under control.

Using this drawing – like many other drawings – Mahema designed a greeting card, with a relevant text briefly describing the history of the hall. These cards would have been seen by many thousands. That this drawing had a ‘planted error’ in it was obvious to none. On the other hand, had I created the drawing with a single vanishing point, as I should have, then, perhaps, people might have thought there was something not quite right about the piece!

* * *

Yaanai Malai (Elephant Hill) is a dominant landmark in the northeastern outskirts of Madurai. When approached from Madurai, this monolith has a certain resemblance to a seated elephant. Dotted with starkly beautiful palmyra trees, this part of rural Madurai once had a character of its own. The paddy fields nourished by monsoon rains receive supplementary supplies of water from large, squarish, irrigation yeatram wells. A yeatram has a long pole with a rope and a large bucket at one end and a counterpoise at the other with a fulcrum in between. Yeatram, which have all but vanished from the rural scene today, were extensively used during my boyhood to draw volumes of water from these wells.

In the early 1950s, on a cool October noon, a school friend and I took a cross-country trek towards Yaanai Malai. Suddenly, an idyllic rural scene presented itself. We saw water-logged fields being ploughed. There was a large square yeatram well from which a wiry old man was drawing water. Yaanai Malai formed an imposing, peaceful backdrop. Monsoon clouds began to gather, darkening the upper sky and softening the light falling on the austere scene. The landscape was placid but the sky was in turmoil and yet there was perfect harmony between land and sky. The sky became darker and light played games on the hill.

Over the years, many of those paddy fields, though not all, have vanished forever. Houses have cropped up where the paddy fields were. But I carry an image of what I once saw in my head and in my heart.

As I grew older, my eyesight kept diminishing. In 1986, when I could not clearly see such scenes, I decided to capture on paper, in ink, the magic of the scene that I had witnessed more than three decades earlier. I could not, of course, reproduce the scene exactly as it was but I did my best to capture the mood and the moment of beauty that was etched in my memory. So I diligently began an assembly job. I remember a distant banyan tree and a few typical rural houses of the time. I included these in the drawing. There were scattered rows of palmyra trees and a few thorn trees with tiny leaves. I included many palmyra trees and one thorn tree in my drawing.

A yeatram well, of course, had a significant place in my artwork. I integrated two farmers ploughing the wet fields. Yaanai Malai, the dominant central aspect captured in ink, was set serenely where it should be. The monsoon clouds which enhanced the beauty of the scene many years ago, enhance the beauty of my later artwork.

This is one of my drawings that has been especially appreciated by many friends. Some talked about the stunning realism of the drawing. I could not have appreciated this piece of artwork without my deep grasp of perspective. When I assembled this drawing, three aspects came into play: Firstly, the rich memory of the rare visual gift that I enjoyed, secondly, whatever artistic skills have been granted to me and, finally, the effective application of the deep knowledge on perspective that I had accumulated.

* * *

Mahema grew up in Madras. From her early girlhood she was fond of jasmine. By the time she was a student at Stella Maris College, she realised that gundu malligai (globular jasmine) from Madurai was very special indeed. As my bride, she wore a tightly knit large strand of globular jasmine from Madurai in her hair. A few months after our marriage, we visited Madurai. She wished to see a jasmine garden in rural Madurai, which we did. She could relate very well to the jasmine pickers, who gifted her a bunch of freshly plucked jasmine which she strung together and wore in her hair.

Later in life, every time friends came from Madurai to Madras, Mahema’s only request was that they bring her a strand of Madurai jasmine. So, when I worked on My Madurai, I naturally decided to include an ink drawing on a jasmine garden in rural Madurai though this was going to be a challenging piece to create.

One early morning in 2003, Chitra of Aravind Eye Hospital and a horticulturalist took me to a jasmine garden. We studied the bushes, the arrangement of the leaves, the hardy straight stems, the cluster of buds and blossoms. We spoke to the jasmine pickers too. I made rough sketches and took photographs.

One could see jasmine buds in nearby bushes which hid much of the buds in the bushes that were beyond. Therefore I chose the horizon line at a higher level which, in turn, enabled me to ‘expose’ the bushes that were behind the frontal ones. I began working on my drawing with large buds in the nearby bushes making them progressively smaller but in larger numbers. This would lead the eye to a group of typical tile-roofed village houses, flanked by coconut palms, with the distant Western Ghats as the backdrop.

No photograph of the jasmine garden – or any jasmine garden for that matter – would resemble my artwork, which gives the illusion of floating above the blooms. Here, I tried to capture the essence of the garden rather than aim for photographic realism. When I completed the drawing in 2003, I experienced a special sense of fulfilment that I had been granted the grace to create such a piece of artwork with my severely impaired vision.

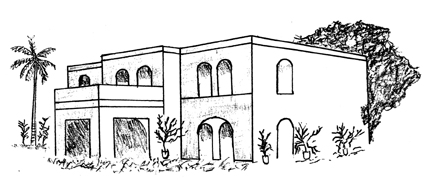

Mahema told me on the phone that we were to go to Cottingley to survey and take pictures of the building for Mano to sketch. She added that it was the official residence of the British Deputy High Commissioner, whose wife wanted an original ink drawing of the house by Mano. Be early, Mahe told me, because the soft early morning light is a little less harsh on Mano’s eye.

We reached Cottingley well on time. It is a sprawling colonial-style house, with a gracious portico, surrounded by waving palms and lots of lush greenery. Understandably, Mano requested Mahema to suggest the right location and angle for the artwork. We clicked several pictures and left.

After a week or so, we went again to Cottingley on another sketching expedition. Acute tunnel vision is a part of Mano’s visual problem. He could see unclearly only a tiny protion of the large house, through the narrow cone of his vision. With all the greenery surrounding the building, he had difficulty comprehending the complex shape of the edifice. So, Mano wanted to get a feel of the building. I explained, as best as I could, its prime architectural features. Mano gave me a piece of paper and asked me to fold it in the shape of the facade. Holding it in his hand, he directed me to lead him close to the house. I did this as much as the cacti and palms would permit. I held his hand and made him touch the building wherever possible. He asked such penetrating questions that I looked at Cottingley in a new light. We then left for breakfast.

It took me two days to print the pictures on A5-size paper. Well before I could send the photographs to him, a letter arrived for me. It was a copy of a letter from Mano to Dr. Venkataswamy (Chief of Aravind Eye Hospital), describing our recent foray and enclosing a sketch of Cottingley as Mano had seen it in his mind’s eye. To my utter astonishment, the quick sketch (below) was a very good replica of the building – a building he could hardly see.

To this day, I am never tired of recounting this tale. To me, it was just one more instance of Mano’s and Mahe’s amazing ability to triumph over disabilities and stubborn refusal to let them get in the way of their enjoyment of life and art. I realised that he did the sketch, not so much using his eyes, but more from his inner vision and a deep sight into perspective in art. As he explained in his letter, once he was able to visualise anything three dimensionally inside his mind, he could put it on paper using his deep knowledge of pespective. The fact is that he cannot see your face even at close quarters, but the reality is that he can draw a building based on touch, feel and sketchy descriptions. That is Mano.

Mano and Mahema, of course, shared with me the final ink drawing of Cottingley (below). I was very happy that I had made my contribution towards the creation of this and other drawings by Mano.

– Joan Rajadas

(who often helps Mano)

|