Recalling early history

The Forgotten Harbour’ (MM, May 16th) made interesting reading. However, the traditional theory mentioned in the article requires re-investigation.

The original firman or cowle granted to the British in 1639 certainly mentions Madras�patam. Hence, it would be tenable that Madraspatam already existed before the so-called founding of it by Francis Day. Same was the case of Chenna�pat�am. S. Krishna�swamy Ayy�an�gar, a noted authority on Vijayanagar history, citing a Telugu source, has mentioned (1919) that Damarla Ayyapen�dra founded Chenna�patam in memory of his father Chenna Nayaka. This information is provided by Ankabhu�pala, son of Chenna Nayaka, in his poetical work Ushaparinayam. Ayya�pendra Nayaka was the half- brother of Ankabhupala. Ayya�pendra Nayaka was also a distinguished soldier who in later years led a military expedition against Chikkadevaraja Wode�yar of Mysore and fell in the battle at Erode around 1670. These details demonstrate that Madraspatam and Chenna�patam were clearly distinct localities. N.S.Ramaswami, an erstwhile chronicler of Madras, opined (1977) that Chenna�patam must have been developed later than Madraspatam. It is also on record that Ayya�pen�dra interposed this “town” Chennapatam between the Portuguese at Mylapore and the Dutch at Pulicat to prevent their constant skirmishes on this boundary.

Apropos Francis Day, larger than his alleged role in the erection of Fort St. George is the role that seems to have been played by Andrew Cogan. It was actually Cogan who transferred the seat of the agency of the Company from Masulipat�am to Fort St. George on September 24, 1641. Cogan made it the chief factory of the Company on the East Coast. Francis Day, on the other hand, had his own problems with the Company. The Company took Day to task for some of his projects and also entered its charge in the Black Book in 1642. However, Day did not seem to have suffered thereby.

The British, after their abortive attempt to set up their base at Pulicat, opted for Masuli�patam. But they continued to be unhappy there and started looking for other settlements. Pollocheere or Pondicherry, Conimeer or Kunimedu north of Pondicherry, and Covelong, north of Mamallapuram, were contemplated before Duruga�raya�pat�nam was chosen. Fascinatingly enough, Pulicat Lake, which once extended upto Durugarayapatnam, was known by the name Pralaya Kaveri. This reference also propels the need to probe further into the history of pre-British Madras and its surroundings extending far beyond the contours of the banks of fisherfolk and their settlements.

The antiquity of Madras�patam with its probable Muslim links is also worthy of being explored. Seethakaathi, that great patron of Islamic Tamil literature (a “Donor par excellence even in his demise”) is believed to have operated a prosperous trade guild from the neighbour�hoods of what is now Chennai. Is it plausible that he also ran a “Madrasa” there? The Arabs also were known to have had active trade contacts with the East Coast from the 11th Cen�tury onwards.

With reference to Dr. Raman’s query (MM, June 1st), and Prof. Sanjeeva Raj’s note (MM, May 16th), the etymology of “Armagam” remains a puzzling one. A 1926 reference to this place calls it “the station of Armagaum” (a slant towards Aru�mu�gam!). Hayavadana Rao, a well known Mysore historian, states that Armagon was the first place fortified by the English in India. Within four years after its establishment in 1626, it was found to be insufficient to supply their commercial needs after a disastrous �famine hit the place. Subsequently, Armagon was made one of the five factories of Masulipatam under Henry Sill.

Historically speaking, in earlier times, a more strategically located trade station was found at Pulicat on the Madras Coast. The Armenians were in occupation of this post in the 1500s. Later, the Dutch established their settlement here in 1609, built a fort and named it Castel Geldria. An early Protestant Mission archival note contains the following description about Pulicat. “It was once a flourishing place of commerce, excelling in the manufacture of a peculiar kind of handkerchiefs, in great demand among the Malays of the Eastern Islands; and at one time, highly esteemed even in Europe”.

Celebrating the birth of Madras from the British period is certainly objectionable, but the much earlier history of Madras should be traced.

Rev. Philip K. Mulley

Anaihatti Road

Kotagiri 643 217, The Nilgiris

Editor’s Note: Please refer to the Editor’s Note in MM, September 16th, page 5.

On the trail of bridges

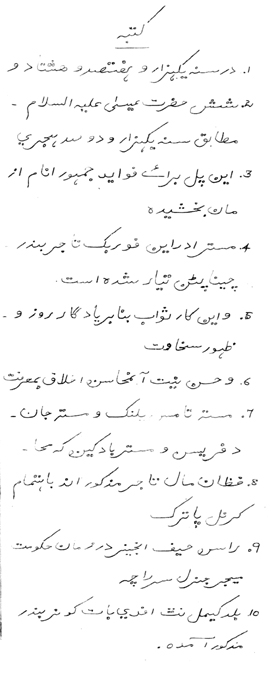

The Fourbeck monument.

...from a translation copy.

While sourced information for ‘Bridges of Madras’ (MM, September 16th and –October 1st) from the State Archives, other information on bridges was seren�dipitously found in �unexpected places.

During ‘Madras Week’ I visited an exhibition in the Armenian Church to learn more about the story of the Armenians in Madras and elsewhere in India. I suspected my subject would be there – the great “Marma�long Bridge” of 1726, built by Peter Uscan. Yes, it was there – with images of two famous paintings done by famous painters. I had seen these images before, but what caught my eye was a com�ment by a naval officer and explorer, Dumont D’�Urvil��le. During his circumnavigation, he arrived in Madras in 1829 and wrote, “(in �Madras) an entire neigh�bour�hood is reserved for Muslims. We go there by the Armenian bridge built on the river Mylapore; this bridge is 365 metres in length with its roadway (and has) 29 arches of various sizes.”

This was the first time I had come across the length of this bridge and the number of arches it had. Also of the name of the river being the ‘Mylapore River’ and not the ‘Adyar River’.

The Persian side...

After ‘Madras Week’, I was back at the Archives. A scholar from the University of California, doing research here, sat across from my table. For nearly a month, we did not speak to each other. Then, one day, a journa�list dropped in to meet me about my –interest in the bridges of Madras. After she left, this scholar, Hannah, spoke to me and told me of a Persian manuscript in the Oriental Manuscripts �Library at Madras University which talked about a bridge built in 1786. This bridge, the ‘Marmalong Brook Bridge’, was built close to the Marmalong Bridge by the executors of a wealthy merchant, after his death. Adrian Fourbeck, an old resident of Madras, had left a legacy to build a bridge on Mount Road across a surplus channel of the Long Tank near Saidapet.

The work was carried out by his executors, Tomas Pelling, John De Fries and Peter Bodkin. There is a small monument to this bridge in the Highways Department’s vehicle depot near Nandanam with inscriptions in �English, Persian, Latin and Tamil on its four faces.

I had photographed this quite some time back and showed Hannah the pictures. She introduced me to a Professor of Persian �languages who showed me the translation by another scholar of the Persian plaque on the Fourbeck monument.

D.H. Rao

8, Elango Nagar Annexe

Virugambakkam

Chennai 600 092

|