|

Much loved, much adored Mandolin Mandolin U. Shrinivas, who remained a boy wonder all his life, was a frail, shy teenager when he appeared on the cover of Sruti’s inaugural issue in October 1983, along with D.K. Pattammal, Lakshmi Viswanathan and Sonal Mansingh. Founder-editor N. Pattabhi Raman concluded his profile of the child prodigy with the passage: “Meteors are transient: they describe a fiery streak in the sky and then burn themselves out. Stars stay with us, adding sparkle to our life. It is the hope of almost everyone who has been exposed to the luminosity of Srinivas’s music (that is how he spelt his name then) that he will turn out to be a star on the firmament of South Indian classical music.”

There are those that believe Shrinivas had accomplished so much in his brief sojourn of earth, that it should not matter that he was snatched away in his prime just as Srinivasa Ramanujan and Subramania Bharati were. It is hard to agree with such a sentiment. At 45, he had many years of glorious creativity ahead of him, his music poised for a greatness beyond what he offered the world over the last three decades. The way he approached ragas, his new interpretations of them in recent years, suggested that the best of Mandolin Shrinivas was yet to come.

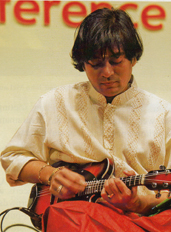

Mandolin U. Shrinivas.

He was all of 14 when Sruti first interacted with him. He had already floored the most demanding rasikas of Mylapore and Mambalam, Perambur and Nungambakkam, on their own home turf in concert after concert, with his spectacular raga essays and swara fusillades. He was tiny, tongue-tied, knew very little Tamil and less English. He was respectful, even deferential in his dealings with parents, guru, mentors, sabha secretaries and media persons, yet he was comfortable in his skin. Here was a boy completely free from self doubt, while at the same time totally bereft of airs.

The boy Shrinivas was a unique amalgam of modernism (in the electrifying speed and magic of his music), an almost rustic old worldliness (in the way he dressed and behaved), and pure genius (in his astounding mastery of both his instrument and raga music). He came from the West Godavari District of Andhra Pradesh, taught himself to play a mandolin that belonged to his father Uppalapu Sathyanarayana’s light music band, and learnt Carnatic music from a vocalist in his native village of Palakol.

The guru, Rudraraju Subbaraju, had been a disciple of Chembai Vaidyanatha Bhagavatar. While he sang his lessons, the boy pupil repeated them on his strings. Shrinivas’s grasp was astonishing, and he soon plunged into classical music and achieved spectacular variations, exploiting to the hilt a tiny instrument that no Carnatic musician before him had ventured to play. He did not have an orthodox pathantara but he made up with his intuitive talent to create a stunning impact on the listener.

His first concerts in Chennai were in 1980 or 1981. An amazing kutcheri at the Ayodhya Mandapam in West Mambalam is still remembered by listeners on whom he cast a spell that day. It was probably a testimonial to Chembai Vaidyanatha Bhagavatar, his guru’s guru. He really arrived with a bang on December 28, 1982 at a concert at the Indian Fine Arts Society. Soon senior artistes were gladly agreeing to accompany him, though it was often an uphill task for the violinist to keep pace with his lightning fast phrases and novel turns of improvisation. Violinist Kanyakumari, mridanga vidwan Thanjavur Upendran, and even special tavil exponent Valangaiman Shanmugasundaram were among his willing, doting accompanists. So were Umayalpuram, K. Sivaraman, Guruvayur Dorai, Srimushnam Raja Rao and others.

It took a while for the prodigy to grow out of the influence of promoters eager to exploit the commercial possibilities his genius promised.

The next decade was a sensational whirl of concerts in Madras and all across India, drawing huge, ecstatic crowds. He was probably Carnatic music’s greatest crowd-puller during that period. His repertoire of raga and compositions was considerable by now and his ragam-tanam-pallavi expositions became quite exhilarating, though he favoured some unusual raga choices.

Shrinivas worked tirelessly at growing as a mandolin exponent while drinking deep of the treasures of Carnatic music, but to him, it was all play. Music was bliss. Whether he was playing the major ragas of Carnatic music, or rare ones, or those with a Hindustani tint, his grasp of their dimensions and nuances was astounding, and he gave expression to them in ways we often did not expect. His music could move you to tears as much as it could make your pulse throb with excitement. The secret was its purity. While he was surely capable of etching delicate raga essays or execute the slow songs of grandeur bequeathed to us by Carnatic music’s great composers, speed and virtuosity became his trademark and won him millions of rasikas.

During an interview in 2008, I suggested to him that it was perhaps time to play what I believed must be music closest to his heart to select audiences in small intimate gatherings. After all, the mandolin was not a loud instrument and he was able to coax the most delicate glides out of it. He told me that he loved large audiences, that he wanted to continue to reach out to the greatest numbers.

Not only did Shrinivas convert an essentially folk music instrument into a mainstream instrument in classical music, he also took it worldwide and collaborated with musicians of several genres. His jugalbandis with Hindustani musicians were exciting crowd-pleasers. His forays into fusion with jazz and Western musicians of other forms were huge successes in front of varied audiences. He also continued to please Carnatic music lovers of the Indian diaspora. In all his collaborative performances, he tended to play second fiddle, letting his counterparts bask in the admiration of the audience rather than show off his own superior skills. When asked about this, his typically modest reply was: “No, that is not true. They are all great musicians in their own right. And fusion concerts are not competitions, are they?”

Thirtytwo years and many conquests in India and abroad after he first appeared in the pages of Sruti, with his ever increasing raga and composition repertoire, after scores of collaborative efforts that left his admirers wonderstruck by his virtuosity, Shrinivas retained the same simple, shy ways and humility unmarred by his supreme confidence in his art. His was not music for those of us who like it slow and soulful. It was fast, dazzling, breathtaking, awe-inspiring, with rarely a long stretch of quietude. Yet, it had soul. It was music that effortlessly bridged south and north, east and west.

Though Pattabhi Raman’s prayer in Sruti’s Issue No. 1 came true and Shrinivas did become a star in the firmament of Carnatic music, the end has come too soon. He was a role model among musicians, ever smiling, always modest, genuinely so. He brought thousands of new listeners in India and abroad into the fold of Carnatic music. His music touched both the lay listener and the cognoscenti. He thus played a major role in taking Carnatic music worldwide. There will never be another like him. (Courtesy: Sruti)

|