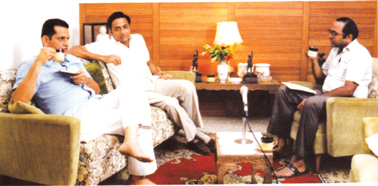

From left to right: Ramanathan Krishnan, N. Sankar and Partab Ramchand.

Matrix, the quarterly house journal of the Sanmar Group, recently brought out to celebrate its 25th year a special issue featuring one article from every issue.

In June 1989 it featured an article in which tennis champion Ramanathan Krishnan, Tamil Nadu Tennis Association President N. Sankar, and sports writer Partab Ramchand discussed the changing tennis scene in India. This is how the discussion went. Much of it holds good 25 years later.

If Bombay is the headquarters of Indian cricket and Calcutta of Indian football, Madras has always been the nerve-centre of Indian tennis. There are many reasons for this, but the predominant one is obviously the fact that Madras has been the home of the two greatest families in Indian tennis, the Krishnans and the Amritrajs. In addition, Madras has always had a great tennis tradition, excellent facilities for playing the game and coaching the young, and a smooth-running tennis administration. This three-way conversation examines various aspects of the game in the State, country and abroad.

Partab Ramchand (PR): Krish, Madras has always been considered the tennis capital of the country. Would you say that this is just because it is the home of the Krishnans and the Amritrajs, or has it evolved through any system?

Ramanathan Krishnan (RK): I would trace the growth back to 1953 when I became the first player from the South to win the national title. People in the South who did not know how to play the game on grass realised that one had to do well on grass to become a good player. I remember when I first played on grass at Calcutta in 1950 I fared very badly. I realised that grass was a fast surface and you had to move quickly. So, I learnt to play on grass because in those days all the important tournaments were played on grass. I won the nationals, I broke the barrier, and then others from the South said that if Krishnan can win the title we can do so too. So they started doing well too. Then I extended the trail-blazing by playing in the Davis Cup, by playing in the USA and by playing at Wimbledon. No one cares if you win a tournament at Beckenham, Bristol or Brussels. You have to do well at Wimbledon to become well known, and you have to do well in the Davis Cup. These are the two big tournaments.

PR: Sankar, I have a question for you. Whenever I talk of Madras being the nerve-centre of the game in India, people cynically ask me, “But where is the system? The Krishnans and the Amritrajs have come up only because of parental encouragement. Who else has Madras produced?” As TNTA President, how do you reply to these people?

N. Sankar (NS): Let me add that in the case of the two families the development has been more talent-oriented rather than through any system. In the Krishnan case, I have known the family for long. It was talent, the parental encouragement and his own efforts that made Krishnan a great player. In the Amritraj’s case, yes, it was again talent and parental encouragement, but by then a system was available and so in their case as well as that of Ramesh Krishnan, in addition to the other questions, there was a bit of system too that played its part in their coming up. Since then the system has come up a lot more, and a lot more families have taken to the game. Today you have a lot of camps, kids of 5 and 6 playing the game, but somehow there are no world-beaters; and here I feel that even if any system is to succeed, a lot of talent is called for if the player is to make a mark in the international arena.

PR: I have been covering tennis for some time and I feel that the infrastructure is there in Madras. You have the camps, the coaches, the courts, the tennis centres. You have a lot of kids playing the game, as you have mentioned. Now it is said that out of quantity comes quality. But don’t you think the quality is lacking.

RK: If you name three top players from here in the last 30-odd years, it is myself, Vijay and Ramesh. Now all of us had a tremendous family background. Without this, we could not have made it to the top. I know my father gave me all support even in those difficult days. I gave the same support to Ramesh, and I am sure Vijay got the same kind of encouragement from his parents. Now maybe you will say not all parents give the same encouragement.

PR: Yes, I was coming to that point. I was talking with H.K. Joshi, the Chief Coach at the TTT (Triangle Tennis Trust), the other day and he told me that parental encouragement is sadly lacking. He said that if there was an exceptionally talented youngster and he pointed out to the parents that the boy or girl could go places if sent abroad or more money is spent on training, the parents always seemed to tell him that tennis is not the only thing, studies are more important and that stifles the talent of the young players.

RK: That used to be the case. They may be saying that on the outside; but I am sure they really want the boy or girl to play tennis seriously.

NS: Today things have changed. In the days of Krishnan and his father, they would never have given any thought that they could make a living from tennis. Today’s attitude is different. Anyone feels, “If I am putting in so much, how much can I get out of it?” The problem is that the initial cost is very high: one, in terms of family commitments, and secondly, the money involved. For example, I saw a few days ago a nine-year-old girl, the daughter of a friend of mine, playing at the MCC courts and was very impressed. She hit the ball harder than older people. Now her father’s problem is that for her to come up, he has to take her to a completely different environment and ...

PR: What do you mean by “different environment?” You mean a different country?

NS: Yes, he would like to take her to the USA or Australia and play on different surfaces and get advanced training.

PR: Yes, but that again costs money.

NS: Yes, so the investment called for is very much higher because the game has changed so much, just to mention one point. Krishnan used to play three or four months a year and then come back to India. Today you have to play almost throughout the year.

PR: Things have changed since your days, Krish. I mean things are more professional these days, right?

RK: Those days it was an amateur sport. When someone asked you what you do, you did not answer, “I play tennis.” It was always tennis and something else, because you had a job. These days it is only tennis, and parents these days want their children to play tennis for two reasons. One, it has become a glamour sport, secondly, it can be a lucrative career.

NS: Back in 1959, Krishnan received an offer from Jack Kramer to turn pro and I remember there was a lot of discussion about what Krishnan should do. Finally, he turned it down. Even though the offer was a large sum of money, he did it because he decided that tennis was a game he was playing for the fame, not to make money out of it. Today the situation is different because no one is strictly an amateur any more. The hard work is probably more, but the dedication is less, because even an average player can make a living out of the game.

PR: Thirty years later, Krish, in a hypothetical situation, if the same offer was made to you, I am sure you would not turn it down?

RK: I turned it down for two reasons. One, I wanted to do well in the Davis Cup and Wimbledon. When Kramer had made me the offer in 1959 I had not done either. I entered the Wimbledon semi-finals in 1960 and 1961, and helped India enter the Davis Cup final in 1966.

PR: But don’t forget that had you not turned down pro you could not have played Davis Cup.

RK: Yes, the rules did not permit this; but if the rules had permitted, I would have taken the money and played Davis Cup too.

PR: We are talking of changing trends, and this is a related topic; sponsorship and the role that companies can play in the promotion of sports and sportsmen, I think it is about time that business houses in India took a more realistic view of the situation and upped the prize money and made job offers more attractive to budding young players, right?

RK: This is a very interesting topic. In those days, how was one to run a tennis tournament? By getting government grants and some donations. In those days we used to get a small amount for our expenses. The big change took place in 1968 with the advent of Open tennis, and one can call Jack Kramer the father of Open tennis. Today, so many youngsters, like Agassi, may not even know about Kramer; but they are reaping the benefits for which Kramer had to struggle. It was Kramer who opened the gates for professional tennis. All the youngsters making money now should thank Kramer for that. Kramer, while sacrificing a lot, made enemies. In those days it was the International Tennis Federation and Tennis Associations which were running the game, and they made the rules and regulations. I think Open tennis came about because some of the tennis federations went too far with the rules. The federations were a bit too tough on the players. In America, for example, I remember the Association used to tell top players like Barry Mackay and others that unless they played in the American circuit they would not be allowed to play at Wimbledon. Kramer fought against this and gave greater freedom to the players. Greater support for the game came about via the public and media. These two are always No.1 for the game, and next come the sponsors. Sponsors have taken the place of the tennis federations. Without sponsors, you can forget professional sports.

PR: But the sponsorship scene has not really caught on in India, has it?

RK: It has in the last few years. I think we have wasted the whole of the 1970s in India in this regard. We did not keep abreast of the far-reaching changes that were taking place the world over since the advent of Open tennis. I feel this is because the AITA has always liked to have some control over the players.

PR: Sankar, you being an administrator, how would you reply to this?

NS: Tennis calls for a different sponsorship. It is not a team game like cricket. What you pay a good tennis player is a pittance compared to what he can earn by himself. You need to nurture him during the early yeas and give him the opportunities to play more tournaments. Players need the sponsorship when they are still young and not when they are established.

RK: Sankar is involved in two things: he is President of the TNTA; he is also a sponsor of sports. As President of the Association, he cannot do as much for the game as he can do as a sponsor. He has a free hand as a sponsor, because he brings in the money. Sponsors should be given a free hand. If there is interference from the associations, they will withdraw and take up some other game. We have been making this mistake in India. I know instances when sponsors have come forward, but then the associations have put too many rules and regulations, with the result that the sponsors have backed out.

NS: In sponsorship, there are people who are still committed to the game and not so much for what they get out of it. A company does it to get advertisement or publicity. But we can support the game in many ways. For example, I have suggested to the TNTA that our company would sponsor the two artificial surfaces to be laid in the city. I doubt whether Chemplast will get anything out of this, but it is more out of interest in the game. There is another aspect to the sponsorship. One has to get the top stars to participate in the tournaments. Those who play in tournaments here are people like Vasudevan and Mark Ferreira who are good players, but then the public have seen the top players in the world on TV or video and so they are really not keen on other players, and if you do not get the top players the sponsors will not come.

PR: Then do you think it will help if Ramesh Krishnan or Vijay Amritraj come and play in these tournaments?

NS: Absolutely. But then we have to make it worth their while.

RK: The importance of sponsors is so much now that even in the US championship, which is one of the Grand Slam events, the sponsors have their say. For instance, this is a two-week tournament and there are plenty of courts. But do you know what they do? They wait for the second Saturday and play the semi-finals at 6 0’clock in the evening, and McEnroe in one year beat Jimmy Connors and the match finished at 11.30 in the night after five-and-a-half hours, and the next day he was scheduled to be on the court against Borg at 3 o’clock. He had hardly 12 to 13 hours’ rest. McEnroe objected to this and said, “This is nonsense; it is a two-week tournament; why can’t you make me play on Friday and give me one day off?” The organisers insisted that he had to play since the sponsors were putting up a few million dollars and they wanted prime time on TV. So you can see how important sponsors are.

PR: Turning to administration, Sankar, to touch upon the national hard court championship, which was held here in February. One criticism was that the tournament was too unwieldy with a lot of entries and a lot of the events held on so many courts. I felt it was difficult to conduct such a tournament. Do you think it would help if the entries for such tournaments are limited?

NS: The main objective of holding the national championship was to bring big tennis back to Madras after more than 11 years. I was particularly happy that despite live coverage of the men’s final on Saturday morning, one-half of the Egmore Stadium was full. I did not expect such a crowd.

RK: I think Sankar did the right thing in having a lot of events and a lot of players. Eventually, you will get good players only if you have ranking tournaments.

NS: In fact, the players came and told me that it was nice to play a national tournament in Madras at the Egmore Stadium after a long time. We are trying to get the Egmore Stadium for our own, and then I believe we could develop the game further.

RK: We have to create more competitions at a junior level, now that sponsorship is coming in.

NS: Krish, you have been watching tennis closely for over 40 years. Who would you say is the greatest player of the era?

RK: As I already said, it is difficult to make a comparison of players of different eras. But I feel Rod Laver is the best. I have my reasons for saying this. It is not because he was my contemporary, but I state it because Laver could win on any surface. The definition of a true champion is to play and win anywhere and on any surface. That is why Laver won two Grand Slams. Secondly, I give very great importance to temperament. Laver could keep his emotions under control, but inside he was a demon who had the killer instinct.

Fixing cricket matches

(By R.K. Raghavan)

The year 2000 undeniably marked a watershed in the nearly three-centuries-long history of cricket. It was perhaps for the first time that dishonesty came to be associated with the game in a prominent and credible manner. As a former CBI Director who oversaw the 2000 match-fixing enquiry, to this day, I am quizzed – not unreasonably – by friends and acquaintances as to whether I believed that the outcome of a match could be dishonestly altered by any player(s).

My response usually is that while the natural course of a game could be tinkered with slightly by a dishonest player acting on his own or in concert with a few of his mates, it is illogical to assert that a whole match could be transformed by a rogue wearing flannels. A few may not agree with me. Nevertheless, I am emboldened to take this firm stand drawing from my more than four decades of experience with cricket in different capacities, including those of a radio commentator and an umpire.

You must remember that the most hardened and avaricious bookie does not also desire this outcome. He wants to make money by merely exploiting isolated incidents of a minor nature which are distinct for their uncertainty and yield themselves to wild and indiscriminate betting. This is a simple exercise in mischief that does not call for any great skill. This is why I will not lose sleep over the recent episodes which have been blown out of proportion by both the media and law enforcement. But we must remember that the current political and business ambience in the country promotes dishonesty in every sphere of life, and cricket cannot remain unaffected by the attendant venality.

I am pained that all those who administer the game have been lambasted for either indifference or collusion with dishonest players and bookies. The charges levelled in this context cannot be disbelieved or ignored totally. But they contain only a grain of truth. To brand all officials as either dishonest or negligent would be unfair. This is particularly so after 2000 when corrective action was initiated in a major way. Severe disciplinary action – including a life ban against three delinquents – was taken. This was meant to act as a deterrent. What more could an administration do? This is why I take the stand that if a player is determined to be dishonest or has a congenitally flawed mental make-up, the harshest of measures will not stop him.

This explains what we witnessed recently with regard to a few IPL players. Just as we see that in the real world conventional crime is not deterred even by draconian laws, we should be prepared for shocks and surprises in the cricket arena. The regulation of severely curtailed access to players, both physical and in communication, has brought about some discipline. But to expect that this would totally eliminate misconduct is unrealistic and is asking for the moon. The nearest parallel is public servant corruption. Institutions like the CBI and the Lokpal may at best have a marginal impact on corruption. It is not very different in the case of those who play a game or administer it. Let us not go overboard seeking a special legislation or demanding more restrictions on players.

Eternal vigilance and less complacence could bring about a somewhat cleaner game which would delight a majority of us looking for skill and entertainment. The IPL is more vulnerable than other formats. But that is no reason to look down upon it as a devalued form of a glorious game.

Let us not be blind to the enormous entertainment it has brought to the average housewife who wants relief from her daily cares of managing the household against spiralling prices and the agonising non-availability of domestic help. In sum, unless the moral fibre of the entire nation and the polity shows improvement, we cannot expect sports to remain insular and clean.

(Courtesy: Straight Bat).

|