|

More about the Madras years of Everett and Ruth Woodman from the blogs of their daughter.

Ninety-five per cent of Indians marry within their own ethnic, religious and cultural communities, said Dr. Shashi Tharoor, member of the Indian Parliament, in a recent speech to the Indian Institute of �Management in Kolkata. It’s fair to guess, also, that a big �percentage – probably most-marriages in India are arranged by parents or family elders.

Wandering Americans don’t fit into this picture very often, but strange things do happen. A Woodstock School alumna told of an encounter she had in Mussoorie with a breathless middle-aged woman who came running up to her on the street, and asked if my acquaintance would be interested in marrying one of her four sons.

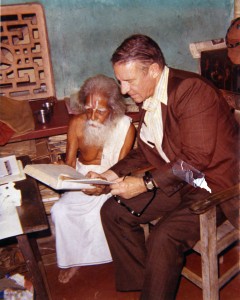

Mr. Patch and Everett Woodman (right) (Photo credit: Colby-Sawyer

College Archives)

My dad, Everett Woodman, had at least two experiences �related to the marriage mart. Once, in Madras in 1950 he was invited to be a go-between in arranging a marriage between two people he knew. The mother of the would-be bride asked if he would put out feelers to the family of the young man. There was a problem – the boy and girl were of different castes – but, nonetheless, my dad cautiously went ahead. No dice! The boy’s parents put the kibosh on the idea. Eventually, both the boy and the girl married people carefully selected by their families.

The second experience I learned about only on reading the correspondence of my dad with his retired schoolteacher friend, P.A. Thiruvenkatachari, his dear ‘Mr. Patch.’

Patch, a Tamil-speaking Brahmin, had been married in 1900, and certainly in the traditional arranged way. He was seventeen years old and his wife was twelve. They were married for seventy-two years, until his death in 1972.

In contemporary Indian slang, ‘Tam-Bram’ connotes �orthodoxy and adherence to Hindu tradition. But Patch was a free-thinker, who had an openness and curiosity and �sympathy for all people of the world. There was a deep intuitive bond between him and my dad, who was thirty-four years younger. Patch wrote to my grandfather calling my dad “a model for the present generation of youngsters”. To my dad, Patch wrote, “You are a good BOY.”

At age eighty-nine, Patch paid my dad the supreme compliment. “I have a curious idea in my mind,” he wrote. Since Everett and he felt almost as close as family, “Why not realise it in fact. You know I have a grandson, eldest boy of my first daughter.”

The grandson was studying for a Ph.D. at New York University. “The boy is fair and nice to look at, a very calm speaker…. Why not think of an alliance with a good Brahmin family? If you think it worth the while, you may meet him and study him. What do you think, my old boy. If this is too much to think of, you may drop it leaving ourselves in status quo. The old tie of Everett and Patch would be unassunderable.”

My dad wrote back, “You know I would have no objection to a good Brahmin-Unitarian match, for to me the similarities are far greater than the differences, so if you want to continue to scheme from Cupid’s corner in Chromepet, give me your next suggestion and maybe I can manoeuvre.”

But no introductions were ever made, no interviews conducted with Patch’s grandson. After that, no more letters came from Patch. A few weeks later, my dad received a letter from Patch’s son.

“My father,” the son wrote, “and your friend, philosopher and guide is no more…. The end was calm and peaceful…. He was not sick or ailing and maintained his health, poise and cheer to the end…. As per the Hindu almanac, he died at the most auspicious hour of the most auspicious day of the year…. He was conversing with me till 3:45 AM…it is given only to a fortunate few to be by the deathbed of divine beings like him.”

My dad wrote back immediately. Referring to his correspondence with Patch of almost twenty years, he said, “The full file of his letters to me will �remain a major treasure…his every message (was) helpful and inspirational…. Patch lives on because of his great spirit…he was truly a master guru of the highest order. He was also �uncomplicated and of delightful good humour, and the essence of the humane qualities that he conveyed so naturally to us all. I am happy that he is safe, and enriched by my memories, and he is in our hearts for always.”

My dad and his dear friend Patch are now both safe, and their correspondence still is, for me, a major treasure.

When on July 21, 1954, Mr. Patch penned his first postcard to my dad, he was 71 years old, long retired, and a library cardholder at the United States Information Service Library in Madras. My dad, Everett Wood�man, then 38 years old, was a cultural affairs officer for U.S.I.S.

“Dear Dr. Woodman,” wrote Mr. Patch. “Our friend Mr. T.V.S. Rao tells me that you carry a very old head on your young shoulder. I wish to verify if it is so…. Do not laugh at my words…I am not suffering (from) dementia praecox. I have pieced together…my �reflections and I shall bring with me a few of them. Let me �explain things more comprehensively in person…. Yrs sincerely, P.A. Thiruvenkata�chari.”

And he did explain things more comprehensively, over the next eighteen years, in at least fifty letters and cards. Since only six carbon copies of letters my dad wrote back are in existence, most of his replies must be �inferred from Mr. Patch’s comments. But the idea comes through, clear as day, of a very special friendship between the two.

In one of his letters, my dad asked Patch for some basic facts about himself. Patch replied: “Since you are rather curious to know the milestones in my life, I should please you by saying: I was born on Dec 23, 1882…”

By 1882, the British were firmly established in India, but elsewhere the British Empire was still growing. It wouldn’t hit its peak for another forty years, when it ruled over roughly a fifth of the world’s population. When the British finally left �India in 1947, Patch was in his 65th year. He saw that empire and others rise and fall.

He also lived through a �dizzying range of inventions, events and transitions: the airplane, the motorcar, two world wars, the global depression, the atomic bomb, decades of struggle for Indian independence, Independence Day �(August 15, 1947), and the assassination of Mahatma Gandhi.

Back to the correspondence. At one point, my parents were awaiting the birth of their fourth child. The family joke was that my dad wanted a baseball team and instead got a ballet troupe. Mr. Patch wrote, “I should be very glad to hear by the next mail that brings me a letter, that you have a boy; not that I discriminate. As the rhyme goes, ’tis ever a joy to have a boy.”

Patch himself had two sons and three daughters. From what he mentions about their education, it seems that he really didn’t discriminate in this area. One son was a doctor; so was one daughter. In the 1950s, his sixteen-year-old granddaughter was already headed for medical school, with Patch’s full �approval. In his matter-of-fact attitude towards women in medicine, he was decades ahead of many Westerners, including my own family.

My mom gave birth to her fourth daughter, and Patch �consoled my parents: “In the modern world a girl is in no way a discountable affair nor a boy a countable one. Children come into this world of their own �accord and not according to our desire. Boy or girl, each one has a purpose to subserve in this world and the parents are only the means to help them in that. We need not discuss any more, but see the newcomer is facilitated in her further stages till she leaves your roof.”

Mr. Patch could be crusty. I guess he figured that his advanced age gave him the right to be so, and temperament played a role as well. “I am in the habit of making no mental reservations of any kind,” he wrote. “I speak as it comes out of my mind.”

One issue on which he was very outspoken was language. He scorned Hindi. He called it a “hybrid Cockney…(with) neither its own characters nor much literature.”

Patch spoke much more kindly about English. “It is sweet,” he wrote, “easy to learn, full vocabulary and universal, being international...It is God's gift for one to know English.” Nonetheless, he qualified this. “English is a very dangerous language...Some words may mean more than what the writer means, causing interpretations more than one.”

|