Registered with the Registrar of Newspapers for India under R.N.I 53640/91

Vol. XXX No. 9, September 1-15, 2020

Lost Landmarks Of Chennai

SRIRAM V

The Theatre Just Off Mount Road

Wellington Cinema! The very name conjures up a different era, of cinema’s early days and heydays. One of the older movie theatres of the city, it was also one of the first to fall victim to the wrecker’s hammer. A commercial complex of multiple colours and unsurpassed ugliness stands in its place now, bearing the name Wellington Plaza.

There are many interesting facets to the history of this theatre, beginning from its name. Before the cinema was a cycle company, run by Rustomji Dorabji. And that was in Bombay, in 1901. The Wellington Cycle Company he founded was the Indian agent for several foreign brands and one of his collaborators was the West End Cycle Co, London. The business prospered and soon Rustomji had opened branches in Secunderabad, Poona and Madras. He also appended the company’s name to his own and became Seth Rustomji Dorabji Wellington. He however appears to have been a man who was forever looking out for new business interests. In 1908, the Wellington Cycle Co briefly forayed into making gramophone records in Bombay and withdrew a year later.

His first venture into cinema screening was in Madras. That was in 1918, when he set up Wellington Cinema and its neighbour, the West End (no prizes for guessing where those two names came from) on General Patter’s Road, just off Mount Road. In the history of the Dravidian movement it is a landmark for it was here that the Justice Party had its first annual meeting, in 1918.

On the space that fronted Mount Road he set up his cycle showroom. The success of the theatres here encouraged him to lease the Cowasji Framji Institute in the Dhobi Talao area of Bombay and convert it into the Wellington Cinema. He also ran the West End theatre at Girgaum.

A third, Venus, would come up later. Rustomji was a complete anglophile and he made it clear that his theatres would screen only English movies. Catering to an Indian audience was nothing short of an invitation to disaster he opined, for the theatre’s fittings would all be ruined for good, their tendency to chew betel leaves and spit being the first of many bad habits. Run a film for one week for an Indian audience he said, and you will spend the next three weeks cleaning the place up. In order to attract the elite audience, the Wellington at Madras, in the time when cinemas were still silent, had a full orchestra that provided the musical entertainment even as the film progressed on screen.

Wellington Plaza – where once stood the Wellington cinema.

Wellington Plaza – where once stood the Wellington cinema.

The details as regards the ownership of the land on which the Wellington stood is hazy. It was in all likelihood owned by Raja Venugopaul Bahadur, a Telugu aristocrat who possessed considerable property and many commercial entities on Mount Road, including the Madras Stable Company and more importantly, the Indian Siegwart Beam Company, which introduced reinforced concrete beams to this city. Rustomji appears to have had a run in with the Raja and more importantly his manager, W.H. Nurse and was taken to court on charges of forgery and cheating.

The case was thrown out in the Sessions Court as baseless, whereupon Rustomji sued the Raja and Nurse in the High Court for defamation. The Raja very conveniently died but Rustomji pressed on with his case leading to a serious legal question on whether damages could be claimed from a dead man. After due deliberation, the law ruled that this was not possible, a verdict that Rustomji accepted with grace.

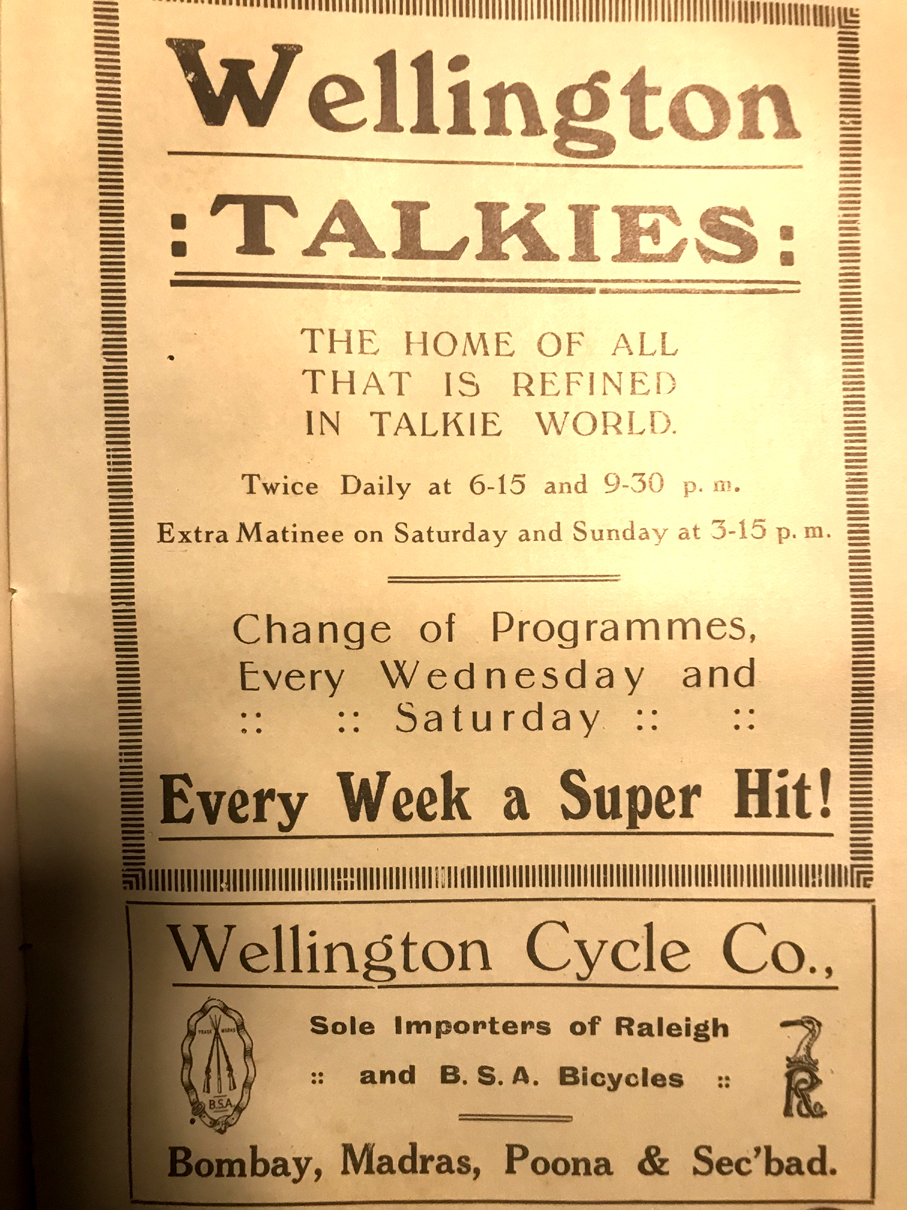

By the 1930s it would appear that Rustomji was dead. Burjorji Dorabji, his elder son inherited the Wellington Cycle Co and the eponymous cinema while Framji, the younger took over West End which he later sold to A.K. Ramachandra Iyer who renamed it Midland. Under Burjorji, Wellington flourished. He appears to have not shared his father’s horror of Indian audiences and opened his theatre to Hindi and Tamil films. It was here, as the projection equipment operator that Dinshaw Tehrani, later to become famed as a sound engineer in Kollywood, worked for a few years. An advertisement of that era declares Wellington to be “the home of all that is refined in the talkie world.” Screenings were happening twice on weekdays – 6.15 and 9.30 pm. Weekends saw a matinee show at 3.15 pm. There was a change of programme each Wednesday and Saturday.

K.B. Sundarambal in Gemini’s Avvaiyyar.

K.B. Sundarambal in Gemini’s Avvaiyyar.Wellington’s heyday was coeval with that of Gemini Studios. Dorabji was a close friend of S.S. Vasan’s and gave the latter’s films first priority for screening. All the Gemini hits premiered here as also several of its duds. Vasan made sure that even the worst of his films ran for 25 weeks at Wellington, thereby qualifying the theatre for an endurance prize according to writer Ashokamitran. But the hits are remembered more, and it was here that Chandralekha released as did Avvaiyyar.

The latter production gave Wellington something more than just a successful release. It was here that a Chief Minister of Madras came to see the film, and what’s more purchased a ticket for it.

Avvaiyyar released in 1953 and as a marketing exercise, Vasan organised a series of special screenings for the prominent figures of Madras society, their opinions being duly recorded and released to the press. One such screening was for Rajaji’s benefit. He was then the Chief Minister. According to Ashokamitran, the CM sat through the film and left, without saying a word but his mere presence was enough publicity. That however was not the end of the story. Post the film’s release, Rajaji came one evening to Wellington to watch the film for a second time. His driver bought the ticket and Rajaji was ushered in and soon, on being alerted, Vasan and most of the senior Gemini staff had arrived. The CM once again watched the film in full and left, in silence. But it was enough for the world to know that Rajaji had seen it twice. By then, the film was on its way to becoming a huge success. Years later, Rajaji’s real views on the movie surfaced in a diary entry. He had found it execrable. And yet why did he see it twice? He does write something about how he had to do it with so much at stake. Vasan was a Congressman and perhaps Rajaji was arm twisted by someone up top in the party to see it a second time.

Sometime in the 1930s, the land on which Wellington theatre stood and much of its neighbourhood, comprising 126 grounds, was acquired by Dinshaw Dadabhai Italia, a prominent businessman of Hyderabad, who would later become a Member of Parliament from that city. The entire stretch of land was named the Dinroze Estate and was soon plotted, built up and rented out. A part of the land was also leased from the Parthasarathy Temple, Thiruvallikeni. It seems that sometime in its history, Burjorji Dorabji or his descendants opted to sell their interests in Wellington to the Italias. By the 1970s, the theatre’s best days were over and it had settled down to showing reruns. Vasan was dead, and his Gemini Studios was tottering too. It soon closed. So too did Wellington. Those who recall its interior then remember it to have been quite rundown. It was a far cry from the time when a fastidious Rustomji refused to cater to anyone but the European elite or when a Chief Minister stood in its lobby while his driver bought a ticket.

The Italias opted to demolish Wellington and build a commercial complex on the 20 grounds of land on which it stood. Nobody would have then believed that the days of the neighbouring cinema theatres too were numbered and within three decades there would be just one or two left.