|

Explaining the concepts behind the new Secretariat complex in Chennai, Chief Minister M. Karunanidhi referred to the inspiration Tamil Nadu can draw from the Uttaramerur inscription. It testifies to the historical fact that nearly 1100 years ago a village had an elaborate and highly refined electoral system and even a written constitution prescribing the mode of elections. The details of this system of elective village democracy are inscribed on the walls of the village assembly (grama sabha mandapa), a rectangular structure made of granite slabs.

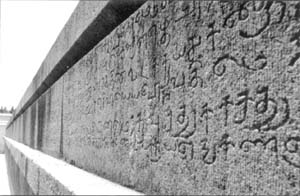

One of the inscriptions in Uttaramerur.

|

“This inscription, dated around 920 A.D. in the reign of Parantaka Chola (907-955 A.D.),” explains Dr. R. Nagaswamy, a former Director of the Department of Archaeology, “is an outstanding document in the history of India. It is a veritable written constitution of a village assembly that functioned 1000 years ago.” Dr. Nagaswamy is the author of a book, Uttaramerur, a Historic Village in Tamil Nadu, which has been published in both English and Tamil. The inscription, he adds, “gives astonishing details about the constitution of wards, the qualification of candidates standing for elections, the disqualification norms, the mode of election, the constitution of committees with elected members, the functions of those committees, the power to remove the wrongdoer, etc...”

But that is not all. “On the walls of the mandapa,” he points out, “are inscribed a variety of secular transactions of the village, dealing with administrative, judicial, commercial, agricultural, transportation and irrigation regulations, as administered by the then village assembly, giving a vivid picture of the efficient administration of village society in the bygone ages.” The villagers even had the right to recall the elected representatives if they failed in their duty.

Uttaramerur, which has a 1250-year-old history, is in Kancheepuram District, about 90 km from Chennai. The Pallava king Nandivarman II established it around 750 A.D.

Its three temples have a large number of inscriptions, notably those from the reigns of Raja Raja Chola (985-1014 A.D), his son Rajendra Chola, and the Vijayanagar emperor Krishnadeva Raya. Rajendra Chola as well as Krishnadeva Raya visited Uttaramerur. Uttaramerur, built on the canons of the agama texts, has the village assembly mandapa at the centre. All the temples are oriented with reference to the mandapa.

Scholars are of the view that while village assemblies might have existed before the period of Parantaka Chola, it was during his reign that the village administration was honed into a perfect system through elections. In fact, inscriptions on temple walls in several parts of Tamil Nadu refer to village assemblies. “But it is at Uttaramerur on the walls of the village assembly (mandapa) itself that we have the earliest inscriptions with complete information about how the elected village assembly functioned,” notes R. Sivanandam, epigraphist at the Tamil Nadu Department of Archaeology.

R. Vasanthakalyani, a retired chief epigraphist-cum-instructor at the Department, adds that the entire village, including infants, had to be present at the village assembly mandapa in Uttaramerur when elections were held. Only the sick and those who had gone on a pilgrimage were exempt. There were committees for the maintenance of irrigation tanks, roads, to provide relief during drought, to test gold, and so forth.

Another feature of the elective system in the village is described by Dr. Nagaswamy: “The village assembly of Uttaramerur drafted the constitution for the elections. The salient features were as follows: the village was divided into 30 wards, one representative elected for each. Specific qualifications were prescribed for those who wanted to contest. The essential criteria were age limit, possession of immovable property, and minimum educational qualification. Those who wanted to be elected had to be above 35 years of age and below 70.”

Only those who owned land that attracted tax could contest elections. Another stipulation, Dr. Nagaswamy points out, was that such owners had to possess a house built on a legally owned site (and not on public poromboke). A person serving in any of the committees could not contest again for the next three terms, each term lasting a year.

Elected members, who accepted bribes, misappropriated others’ property, committed incest, or acted against the public interest, suffered disqualification.

– (Courtesy: TCC Digest)

|