|

One of the distinctive features of Fort St. George is its flag-staff, its immense height of 148 feet towering over the rest of the mostly low topography. In fact, it is one of the tallest flagstaffs in the whole country.

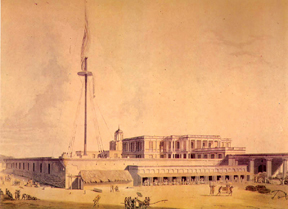

The Fort by William Daniells showing c.1833 flagstaff (Courtesy: Madras

Chamber of Commerce and Industry collection).

The original teak mast stood erect from 1688 till 1994 when it made way for a steel replica. The origins of the monumental teak beam are rather hazy. The story agreed upon is that it was the mast of a ship that sank off Madras in the 1680s. The beam was stored in Fort St. George and came in handy in 1687 when Elihu Yale took over as Governor. Permission was received from King James II of England for Fort St George “to wear his colours”, which meant that the King’s flag could be flown from the ramparts. The Fort’s Diary and Consultation Book for 1688 has it that “the Garrison and Train’D Bands are therefore order’d to bee in Arms and the Chief Inhabitants of all Nations invited to the solemnity.”

The event took place on June 12, 1688 when, it is recorded, the Governor made a “handsome collation upon the Fort House Tarrass”. The garrison and trained bands comprising 100 English men marched around the Fort while the Governor and Council, the free merchants, the important natives of Madras and representatives of other nationalities gathered at what was known as the English bastion of the Fort. This no longer exists, but it formed the southeastern corner of the old Fort which, as we saw in the last instalment, was then nothing more than the Fort House and a little more.

The teak beam was erected to form the flagstaff and Yale hoisted the Union Jack on it. He then “opened a glass of Toby” and asked everyone to drink to “our Gracious King’s health & Royall families & his happy long reigne”. The soldiers, who were “as merry as Punch could make them” shouted their hurrahs and the guns boomed 31 salutes for the king, 21 for the East India Company and 19 for Sir Josiah Child, the domineering Governor of the East India Company who sat in distant England but kept a sharp eye on what was happening in Madras. The ships in the roadstead answered the salute and it must have been a noisy evening.

H.D. Love in Vestiges of Old Madras thinks that the clerk who documented the evening may have erroneously written ‘toddy’ as ‘toby’. But what is interesting is that Yale University has a tradition of ‘Elihu Yale Toby mugs’, which are all made in the profile of the former Governor of Madras. First modelled in 1933 by Prof Robert G. Eberhard of the Sculpture Department of the University, these have since been in production. Mugs from the original batch, brought out by Josiah Wedgwood, are now collectors’ items!

But to get back to the flagstaff, it has never been properly established as to when it made the shift from the English bastion to the centre of the eastern face of the Fort. In 1697 it was where Yale had installed it. “On the south east point is the standard” wrote Dr. John Fryer that year in his account of the Fort. Sometime later, it shifted to the Parade or Fort Square. By the 1780s, it appears to have made it to the eastern face of the Fort. Even then, it appears to have moved a couple of times. A painting by F.S. Ward (Fort St. George, looking from the North West Curtain towards the St. Thomas Gate) done in 1785 shows it pretty much where it is now, but another painting by William Daniell in 1793 shows it at the southeast corner of the fully constructed Fort, above the St. Thomas bastion. But by the early 1800s, it had definitely made it back to the ‘Great Bulwark’ above the Sea Gate where it remains.

For three years, 1746 to 1749, when the French occupied Madras, their flag flew from this post. According to Mrs Frank Penny in her Fort St George, Story of Our First Possession in India, when Madras was returned to the English in November 1749, their first act was to lower the French flag and raise the Union Jack on the flagstaff. By 1801, it was such a symbol of Madras that when the Marquis of Wellesley, then Governor General of India, commissioned a portrait of himself to commemorate the British victory over Tipu Sultan, he was depicted seated in a pillared verandah with the Fort St George flagstaff in the background.

What is a wonder is that the flagstaff endured for so long and survived bombardment by the French from the sea in 1746 and 1758. The second attack was the more vicious, when not a single building in the Fort was spared. The flagstaff having then been within Fort Square must have afforded it some protection. Perhaps its sheer staying power created a legend that was most popular in the early 20th Century, according to Lt. Col. D.M. Reid. He notes in his Story of Fort St George that the troops believed that “a ship was blown up the beach in a great storm, and had one mast remaining upright. The mast was used temporarily for signals and was so useful that it was left there and was built over, and today, under the masonry, the old ship sleeps in her solid foundation.” But as to whether it survived in one piece is not certain. Records of a cyclone on May 8, 1820 have it that the upper part of the flagstaff was carried away along with the signalling crew. That regular repairs were carried out is evident from House of Commons papers from the 19th Century. “Tarring the rigging” of the flagstaff was a routine expenditure.

The morning of January 26, 1932 saw considerable commotion around the tarred rigging. Arya Bhashyam, a freedom fighter, had shinned up the ropes, climbed the 148 feet, torn down the Union Jack and hoisted the Indian tricolour. He was arrested when he descended and on refusing to express regret for what he had done was sentenced to rigorous imprisonment. Bhashyam would, after Independence, refuse the pension awarded to him as a freedom fighter and eke out his life doing portraits of Subramania Bharati and sculpting statues and busts of Mahatma Gandhi. The official portrait of Bharati with the handlebar moustache is his and some of his works adorn the Tamil Nadu legislature.

On August 15, 1947, the Indian national flag was hoisted on the flagstaff at 5.30 am. The flag unfurled that day is now a treasured possession of the Fort Museum, displayed in the third floor. It is the only surviving flag among the countless ones hoisted across the entire country that day. But what had survived wind, weather and war, could not escape the clumsy removal in 1994 to make way for the steel replica. The wooden mast had to be cut to pieces and is now confined to some unknown yard in the Fort. It would perhaps have been more appropriate if the old teak beam had been preserved in entirety and erected elsewhere in the Fort with protection from the elements. What a sight it would have been!

|