| (ARCHIVE) Vol. XVIII No. 10, september 1-15, 2008 |

|

|

HERITAGE

–

who’s responsible?

|

|

(by A Special Correspondent)

|

|

|

Who is responsible for Heritage? I, You, We, Us, They? All of us must answer this question. The conservation and preservation of Heritage is everyone’s responsibility. All of us, and not just the Government, have to care for Heritage – for our living traditions, our composite culture, our natural environment, our architectural masterpieces.

INTACH’s Heritage Education and Communication Service (HECS) has set the ball rolling for what could be a major campaign to protect the national wealth of heritage.

Earlier this year, HECS designed a new programme titled Citizenship Education and Heritage. At its first workshop in Delhi, teachers were asked to discuss the idea and concept of citizenship. They were also asked to list adjectives that described an Indian citizen today. The answers were as varied as the mindset they reflected: Laid back; Indifferent; Complainers; Aggressive; Conformists; No civic sense; Selfish; Emotional; Caring; Curious; Sensitive; Enthusiastic; Friendly.

The teachers discussed the Indian Constitution and how it defines the duties and obligations of an Indian citizen.

Those great thinkers who designed the Indian Constitution had a clear idea about the citizens’ responsibility towards Heritage (as elaborated in 51A. Fundamental Duties). The salient clauses of direct relevance to our duties towards Heritage in this regard are:

To value and preserve the rich heritage of our composite culture;

To protect and improve the natural environment, including forests, lakes, rivers and wildlife, and to have compassion for living creatures;

To develop the scientific temper, humanism and the spirit of inquiry and reform.

Heritage for many people is not their problem, it is somebody else’s problem, somebody else’s responsibility. They think it is the function of the Government to look after Heritage – while their job is to look after themselves and the immediate future of their families.

Perhaps people do not care because they think Heritage is about the past and irrelevant to their daily life today. India is changing rapidly, maybe some people even believe that Heritage preservation is out of sync with development and holds back our progress.

William Dalrymple’s City of Djinns perceptibly observes:

“You see actually in India today no one is thinking too much about these old historical places. India is a developing country. Our people are looking to the future only.”

The thought echoes many voices. It is not surprising that Heritage is often misinterpreted and undervalued by State Governments and local authorities. The general misconceptions persist that our Heritage is remote from people’s daily lives, that it is not a bread and butter issue that merits immediate and priority concern given the constraints of funds. Local authorities, who have an executing role to play in protecting this national wealth, fail to understand the contribution Heritage makes to the quality of life, enhancement of environment, and the socioeconomic benefits to be gained for all citizens within their domain.

Recent years have seen enormous damage to and loss of priceless Heritage, traditions, and artistic skills. More so in today’s world of rapid globalisation, frequent violence, general insecurity, etc. where the cultural and natural environment are under constant threat.

On 27th January, 2009 INTACH will celebrate its Silver Jubilee. Memorandum of Association outlines the role of INTACH Members and relationship of citizenship and Heritage clearly:

To create and stimulate an awareness among the public for the preservation of the cultural and natural heritage of India and respect and knowledge of past experience and skills.

To undertake measures for the preservation and conservation of natural resources and cultural property.

To undertake appropriate measures for the preservation of not only historic buildings, but also of historic quarters and towns and domestic architecture displaying artistic or skilled craftsmanship.

To act as a pressure group by arousing public opinion when any part of the cultural or natural heritage is threatened with imminent danger of damage or destruction.

In INTACH’s 25th year, the policies and campaign work of all INTACH Chapters will demonstrate the contribution that Heritage makes to people’s everyday lives by illustrating the social, cultural, economic and environmental benefits to be derived by heritage conservation. To remind people that Heritage is our memory and identity that define who we are and what our country is and could be.

HECS has been actively involved in developing public awareness of Heritage among young people. The next phase is to draw attention to the intrinsic value of the country’s historic legacy.

The protection of Heritage, be it historic, natural, intangible, local, demands the active involvment of responsible citizens. We need to create generations of Indian citizens who respect and enjoy their past. Historic cities, natural environment, monumnets and museums, are all part of living inheritance, a critical component of national identity in a rapidly changing world. (Courtesy: INTACH Virasat)

|

|

|

INTACH looks at Corporation, Tranquebar,

coastal encroachment

and an award

|

|

|

The Roman Trail

Arikamedu – Its Place in Ancient Rome-India Contacts by INTACH member Dr. C. Suresh, a noted archaeologist, was published by the Embassy of Italy’s Development Corporation Office. The book documents the ancient trade ties between traders from the Roman Empire and Arikamedu near Puducherry, which was once a flourishing port during 300 BC-600 AD. The Romans imported spices, gemstones, ivory, textiles and peacock feathers, and brought in return wine, gold, silver, copper and antimony to India.

The book offers practical suggestion to revive Arikamedu as an archeological and tourism centre. Dr. Suresh has been conducting a unique tour titled Roman Trail Tour himself on behalf of the Tamil Nadu Chapter, Chennai, since 2002, taking small groups of serious tourists and students to various Roman sites in South India, including Arikamedu.

|

Tamil Nadu Regional Chapter (Chennai) Convenor P.T. Krishnan has drawn up a selection criteria and process for appointment of a Conservation Architect for the restoration of the Ripon Buildings. It was accpeted by the Chennai Corporation.

Some of the technical qualifications laid down are minimum five years’ experience in the field of building conservation and restoration; consultancy work to the value of Rs.2 crore during the last five years; a degree in the field of Conservation Engineering/Architecture; and supporting staff of at least two draughtsmen and one Civil Engineer with experience in the field for monitoring conservation work. The scope of work is also defined.

This is a valuable prototype for all Chapters. INTACH’s Head Office is undertaking a similar exercise to draw up a panel of conservation architects, laying down stringent criteria for selection, for deployment at projects undertaken by INTACH’s Architecture Division.

* * *

The National Museum of Denmark (NMD) had requested INTACH Tamil Nadu (Chennai) to assit in the restoration of the Danish Governor’s Bungalow at Tranquebar with the participation of the Puducherry Chapter. Convenor P.T. Krishnan has written to the Commissioner of Tourism, Dr. M. Rajaram, for authorised entry to the Bungalow for a specified period, as it is owned by the Tamil Nadu Tourism Development Corporation.

The NMD proposes to channelise funds through INTACH Head Office, with Bestseller Foundation, India (BFI), maintaining it as a Cultural Centre and financing its maintenance, activities and programmes for an initial period of five years on completion of restoration. This Centre would also promote research and studies in the unique heritage of Tranquebar with its Indo-Dutch connection. A special effort will also be made to involve the local citizenry’s participation right from the start of the restoration. Convenor Krishnan has requested the Commissioner to expedite the setting up of the proposed committee comprising official and non-official members for supervising and executing the project.

* * *

Nagercoil Convenor Dr. R.S. Lal Mohan is concerned that considerable damage is being done to the Kanniyakumari town coast in the name of tourism development. Kanniyakumari is officially recognised as an international tourist centre and heritage site and, hence, disruption of the coastal morphology cannot be allowed within 100 metres. However, the Kanniyakumari Town Panchayat has leased out a stretch of 1.5 kilometre coastline for a beach hotel for a period of 3 years, with a new construction coming on the sand dunes just 10 metres from the high tide level changing the entire morphology of the coast. Local NGOs demand a transparent investigation. The area has a 37,000-year-old coral reef formation. This is in gross violation of the Coastal Zone Notification, 1991 and the Coastal Zone Management Notificatin, 2007.

Convenor Mohan appeared on Chennai-based Makkal TV to expose the activities involved in such lease agreements and building operations. The one-hour programme elicited feedback from many sources across the country, as this is a familiar malaise of urban development in all big cities. The Chapter has filed a case in the Madurai Bench of the High Court. The hearing is expected shortly.

* * *

Puducherry Convenor Ajit Koujalgi and the Puducherry Chapter have been selected as participants in the Shanghai World Expo 2020 where Urban Best Practices from nearly 50 select cities across the world will be showcased. The theme of the Expo is “Better City, Better Life”. The World Bank and the Shanghai Expo Committee have identified Puducherry and Ahmedabad as two cities from India that fit the bill.

The invitation stems from Puducherry’s successful partnership with INTACH to develop an integrated programme for urban environmental management and heritage preservation.”

Puducherry (earlier called Pondicherry) Chapter jointly with the Municipality will project Asia Urbs Programme that was undertaken in partnership with the European Commission and the two European cities of Urbino in Italy and Villeneuvesur-Lot in France during 2002-2004. (Courtesy: INTACH Virasat)

|

|

|

Heritage Clubs of

two

TN schools in

Top Five

|

|

|

|

Sri Sankara Vidyashramam Matriculation Higher Secondary School, Chennai, was one of India’s best School Hertiage Clubs. The others were Blue Bells School International, New Delhi, GKD Matriculations Higher Secondary School, Coimbatore, Shree Satya Sai Vidyalaya, Amar Vilas Complex, Jamnagar, and the Oxford Grammar School, Hyderabad, which won the Best Heritage Club Award 2007-08, presented by INTACH’s Heritage Education and Communication Service.

|

|

|

Madras Canvas II

Need to stretch it across a larger frame

|

| (by Sadanand Menon) |

|

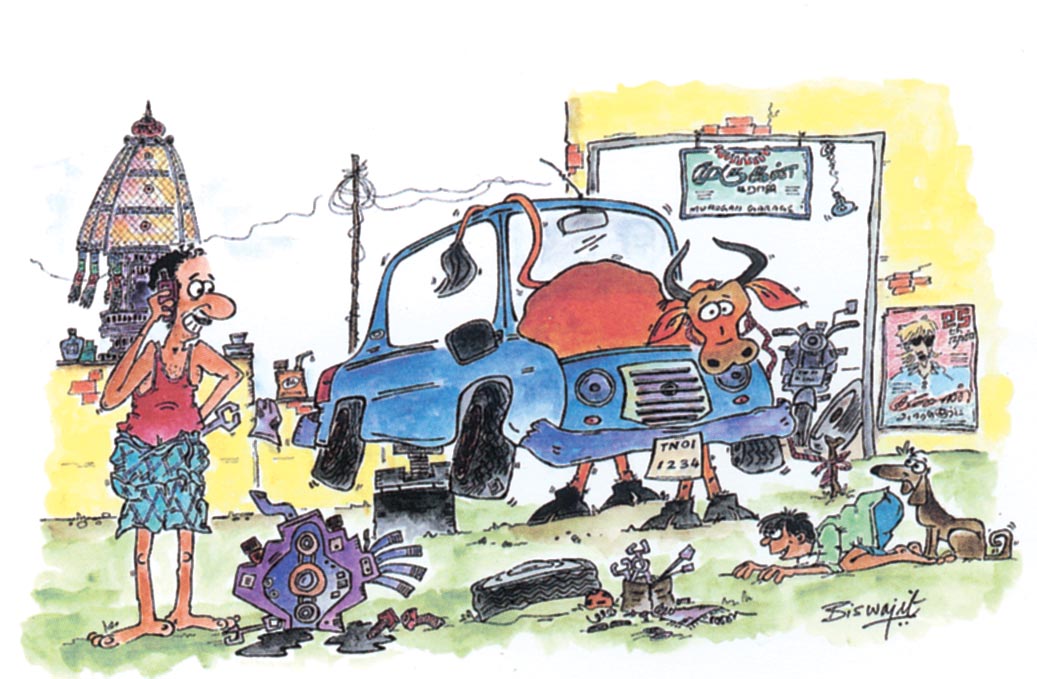

I think, I’ve found the perfect replacement for a petrol engine! (by Biswajit)

Watercolour, ink on paper 11” x 16”

Monsoon by Douglas C.

Watercolour on paper, 31” x 21”

Ganesha by Geetha M.S.

Silver plated copper, 13” x 11

Idly, photography by Shashikant D.

Untitled I by Jacob Jebaraj

Serigraph on metal and

enamel paint 36” x 24”

Chennai and its Backwaters by Venkatapathy D Dry pastel on paper 30” x 20”

|

Now that a collective, representative exhibition of the works of city’s artists which has come to be known as ‘The Madras Canvas’ seems well on its way to being an annual feature in connection with Madras Week, certain questions need to be posed which are commensurate with the spirit of the venture.

One is an old question. Can a city, its impulse, its muse, its psyche be defined by the art practices? If Paris, New York, London or Tokyo can be measured by the kind of engagement and contention provided by the artists inhabiting these cities, what can be Chennai’s score on this scale?

Is this city’s art able to set up a dialogue with its history? Is it able to be a catchment for a wide range of assertions, interpretations, representations and contradictions that the city is inevitably a composite of? Can this city’s art be seen as an overt or covert critique of the city? Is the city’s art a palimpset on which we can read its future through a spirited interrogation of the present? Does this city respond to the creativity of its artists as something of functional value? Or is it entirely marginal to the needs and moods of the city, occupying a desultorily elite niche? Or does it see art as having merely decorative potential? Or does the city run scared of its artists and their unerring power to expose what is merely surface and gloss and demand accountability from the powers-that-be?

Many questions, not too many easy answers.

The present exhibition is neither exhaustive nor necessarily adequately representative. Yet it exudes a certain flavour. There are about a dozen artists, all graduates of the Government College of Art, from the assertive post-Independence era of the 1960s and 1970s; another dozen or so from the reflective middle phase of the 1980s and 1990s; and about thirty from the relatively more docile and cluttered phase of the present decade. Four photographers and a couple of cartoonists, completes the picture.

Essentially what we get to observe in this assemblage is the significant shift in material, modes and methods that has happened in the artistic expression in the city. From an art school practice of conventional media like oils, watercolours, ink and charcoal on the one hand and bronze and granite on the other, there is a conscious breakthrough from the bind of the plastic medium to seek new pastures in stainless steel, welded copper, silver-plated copper, brass, serigraph on metal, woodcuts, digital prints, fibreglass, resin, mixed media with plywood, enamel paint, inkjet on canvas, constructed and architected surfaces and even organic material like leaves, fruits, seeds.

If the immediate decades subsequent to national Independence seemed a little more organically connected with their immediate past, the present moment gives us no such comfort. The explosive and dramatic shift to new media and technology by the city’s artists has also initiated a robust debate on the tension between the classical and the contemporary. The artistic landscape of the city is now rippling with both risky and magical practices, opening new windows to perception and provoking a more critical engagement with its content. For me, the work of a Douglas, a Palaniappan or a Benitha Percival, for example, pose a sharp counter-point against a body of ‘comfort art’ prevalent in the city.

Some significant areas of contradiction bear mention. After its modest beginnings in 1850 as a facility for anatomical drawings and subsequent consecration as the Madras School of Arts and Crafts, the next almost 160 years has not necessitated the setting up of at least one more art school in the city, even though there has been an algorithmic expansion to the city’s population during the period. Over the past fifty years, in fact, this once centre of excellence has slowly sunk into a state of dilapidated misery and constrained non-functionality. Surprisingly, it still throws up every year a fresh bunch of highly talented graduates. But if during the first three decades of the School, its students were producing craft-based objects which became a rage, students from here were positively contributing to the new urban metropolis that was emerging. Students of the Arts School helped add value to the buildings along the Marina Beach like the Madras University complex, the Presidency College and so on by working on elements in these buildings, from stained glass to woodwork, stonework and metalwork. Even the decade after Independence, the School and its students helped its first Indian Principal, Devi Prasad Roy Chowdhury, create stunning stone sculptures for the seafront, like ‘The Triumph of Labour’ and ‘Gandhi’s Dandi March’. It is significant that in the next fifty years, the School’s presence in the city and its contribution to the city’s public spaces has been insignificant. Should this be measured as a decline of official interest in ‘modern art’, in the wake of the strident, pro-Sangam period art of the Dravidian movement, which began to dominate the State from those years?

Of course, recently, the city artists have been given the first ‘public arts commission’ in Chennai, when they were asked to contribute works of art along the roadside in the ‘I.T. Corridor’, from Madhya Kailash to Tidel Park. But, then, the ‘I.T.Corridor’ is hardly Chennai city; it’s a new marker of globalising assertions.

The Cholamandal Artists Village posed an alternative in the mid-1960s. But this was already a retreat from the city to the idea of a rural idyll in Injambakkam. It was clear that this, first-of-its-kind, cooperative of thirty-odd artists were not prepared to get ‘contaminated’ by the attractions of new urbanisation and wished to make a statement by dissociating itself from the ‘commercial pollution’ of the metropolis. Already, the artistic sphere was getting invaded and challenged by a new culture of the visual and the spectacular, linked to the rapid rise of techno-electric media like the cinema. This, along with popular illustrated periodicals, came packaged in loud, garish, kitschy cover pages, posters, hoardings. It was a cosmos far removed from the more lofty concerns of the artist. The irony now is that all these disrespected modes of art in the margins have returned to grab centre stage, either as accepted artistic practice or as the technical craft base which the urban artist of today learns to integrate into his/her work. The skill as well as materiality of the hoarding, poster and graffiti artists has become the fuel of much that is called post-modern art in the city today.

While I am excited by the idea of ‘The Madras Canvas’, I feel one more important point needs to be laid on the table. This has to do with the infrastructure for the arts in the city. As already pointed out, we are a city that has had only one college for the Fine Arts in 160 years. Sure, Stella Maris College does now have a full-fledged department for Fine Arts. But can an eight-million-population-city feel content with this? Educational infrastructure apart, let’s also look at available gallery space for exhibitions, the critical discourse around art, the culture of media engagement, the status of art archives or libraries, the status of publications in local or other languages on artists and historical trends, etc. It is obvious that on all these fronts Chennai, as a city, has yet to get overly enthusiastic. Much collective action by the artistic community as well as concerned citizens will be needed to make a significant difference here. ‘The Madras Canvas’ can, in fact, emerge as a catalyst in this process.

‘The Madras Canvas’, then, needs to be interpreted as a promise – a promise the gallery makes to itself to realign its priorities, even as the city races ahead in its dream to be a new Singapore or a Shanghai. It is clear that only a new realignment with arts will enable this city to confer upon itself the dignity of an honest and civilised quest, a new urbanisation that leaps over the physical, psychological and aesthetic violence that a city has come to represent in our times.

Undoubtedly, we need to stretch the Madras Canvas across a larger frame.

|

|

|

The Inner Wheelers had a ball

|

| (A.S.R.) |

|

|

‘Namma Madras Nalla Madras’ said the banner. And this vibrant city of ours inspired such a carnival – swishing Kanchipuram silk sarees, maa Kolams, poo thoduthal, murukku sutthal, kummi, kolattam and a host of competitions – in which about 300 members of Inner Wheel District 323 came together to celebrate Madras Day at the Alumni Club.

Judges (The Mylapore Trio) were agonised by over 40 varieties of idli to choose from. This was the forerunner to an almost equal number of entries in the ‘Traditional Sweets’ category. Photographs of old and new Madras exhibited unusual perspectives of everyday locales in the city. Members vied with each other to make artistic garlands of flower with the traditional mallipoo and naaru. In another corner, sounds of laughter accompanied the attempts of those involved in making murukku. Maa kolams showcased the imaginations of the participants.

Onstage competitions included a rampwalk in traditional attire and jewellery, skits, adzap, and, just a minute on, well-known locations of Chennai. A video on environmental concerns put together by members was also presented. And members worked their braincells and memories over a quiz on Chennai.

A chorus of four voices set off a melodious medley of Maitrim bhajatha, Kurai Onrum Illai and Santhi Nilava Vendum. Chief Guest S.V. Sekhar could not help singing along! This was followed by a well choreographed kummi-kollattam Kollywood fusion dance. What a burst of rhythm and colour against a tasteful backdrop of Kanchi silks, Mayil Kann Veshtis and Maavilai!

The morning proved beyond a doubt that traditional arts and skills are alive and well in Madras that is Chennai.

|

|

|

|

|