|

(Continued from last fortnight)

Government insisted that an estimate be given for approval for construction work whatever the cost. Unless approval was obtained, no work could be started.

If the estimate was exceeded in the final account, Government needed to know the reasons for the excess amount spent.

Lieutenant Thomas Fraser, who built St. George’s Bridge, was censured for exceeding the estimate. His commission and benefits were all withheld.

In his defence, he brought to the notice of the Governor that when the work on the foundation was completed, he was instructed to realign the whole bridge! Once again he had to sink wells for the foundation, and the piers and abutments were raised. Still, changes continued to be made, and he complied with them all. These changes added to the final cost for which he was not responsible. The Governor accepted his plea and restored all his benefits.

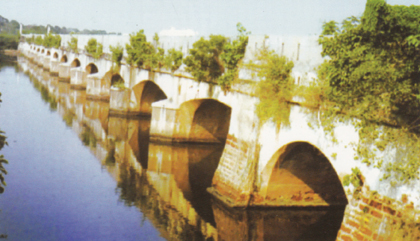

In another instance, the great 18-arch Elphinstone Bridge was completed success�fully and the Military Board was all praise for the Superintending Engineer who gave the people of Madras a grand structure. But not so the Governor. He de�mand��ed an explanation from the Military Board for the �excess over estimate, mainly �because the Court of Directors had put a cap on expenditure before giving their approval.

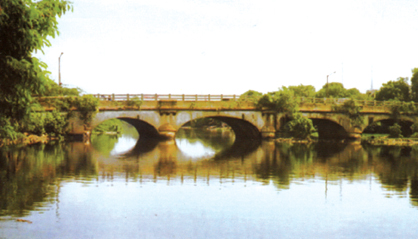

Law's Bridge, Iyah Mudali Street, River Cooum.

M.K. Amman Koil Bridge, M.K. Road, Buckingham Canal.

The Superintending Engineer gave a statement of costs involved in two other bridges to prove his work was carried out most economically, but the bailing of water for foundation building was most unexpected. He stated that the river was �always full of water. While keeping the cofferdams dry, he had to use extra persons for bailing water. After protracted arguments, the issue finally came to a happy end.

* * *

The Government decided in 1840s that all ‘works’ should be given ‘on contract’. When the time came to build a new bridge across the Cooum in Chinta�dri�pet at the same location where, once, the suspension bridge was, the Military Board invited tenders and gave the contract to two local maistries, whose quotation was much lower than the estimated cost.

Neither Military Board nor the Government paused for a minute to ascertain whether the maistries were capable of building a large bridge. They gave them the work, but not without a security.

Having faced all kinds of �difficulties, the local builders gave up the project half way. The work was taken over by the Superintending Engineer, Presidency Division, and com�plet�ed in 1848.

In the meantime, the lead maistry died and the creditors began putting pressure on the Military Board to return the promissory notes given by the builder. The Military Board sought the Advocate General’s opinion and he was forthright in stating that “no notice should be taken of the application in question,” as it was “a fraud of frauds.” This was in 1854.

St. George Bridge, Mount Road, River Cooum.

Elphinstone Bridge, River Adyar.

* * *

In 1840, the Military Board wanted to erect a bridge near Ashton’s shop (present-day Har�ris Bridge). But some “influential natives” did not want to give land for the purpose of a new road.

Another road was proposed along the river from the western end of the bridge towards Marshall’s Road and one northwards to St. Andrew’s bridge. When the Government tried to acquire land under Section I of Act XX of 1852, it was not clear whether it would apply to the Presidency. So the Government brought another Act of 1854, under which it could take over private lands compulsorily and pay due compensation. Thereafter the roads were completed and the bridge built.

Today, many of our road and bridge projects are stalled by vested interests because of lax legislation.

* * *

A bridge on South Beach Road needed urgent repairs. Also its wooden handrail needed replacement and its arches needed plastering. On further inspection, it was found one arch had sunk.

A couple of years later, the Military Board wanted further funds and provided an estimate. The Governor was very curious to know why the bridge was not inspected initially. He also wanted to know who was responsible for the regular maintenance of Presidency Bridges. If there was someone, why had he not carried out his work sincerely?

* * *

A bridge near Ashton’s shop was designed with a width of 22 feet between parapet walls. In 1846, when construction was about to start, the Military Board realised that the bridge would be too narrow and suggested that a minimum width of 30 feet with 5 feet raised causeways on either side for ‘foot passengers’ safety, thus in total 40 feet width was a must. They felt that in the distant future, with the city expanding, and com�par�ing with the width of the bridges elsewhere, Government needed to act on this suggestion and increase the outlay sanc�tioned in 1846. The Govern�ment accepted the suggestion.

Even today we see just two-lane new bridges. What will happen after 50 years?

* * *

Many of the city’s bridges were built with chunam and bricks and are 150-plus years old. They were designed for the transport system of those days, namely bullock carts, horse-drawn carriages and, of course, gun carriages. They served well not only in those days but still do so. When Government wanted to broaden or widen the roads, the immediate thinking was to demolish the old bridges and build new, broad ones. Nobody thought of building a bridge on either side of the old bridge, so we lost beautiful General Hospital Bridge, Elephant Gate Bridge, Hamilton Bridge (all, across the Buckingham Canal) and, lastly, Munro Bridge in Chetpet and the one in Aminji�karai over the Cooum.

(Concluded)

Text and pictures by D.H. Rao

Through the painters' eyes

Famous painters have left us beautiful paintings of the city’s graceful arch bridges:

Armenian Bridge: William Hodges

Painted in 1780, gives the earliest view of the bridge with pointed arches, and with some structures above the roadway.

Armenian Bridge: Thomas Daniel

Painted in 1792-1793 when he, along with his nephew, William Daniel, visited Madras. The arches are more semicircular.

Armenian Bridge: Justinan Gantz

Painted in 1840-45. His painting is a distant view, with the river in the foreground. Another painting shows the huge pillars at the approaches.

Wallajah Bridge: Thomas Daniel

This bridge, one situated by the southwest entrance of the Fort, had seven arches. Painted in 1820, just after renovation, by Major De Havilland.

St George’s Bridge: Lieutenant Thomas Fraser

“A view of the Bridge over Chintadripettah River, near Government Garden Madras.”

The Superintending Engineer who built the bridge in 1804 painted it himself in 1805. He presented it to Sir John Sinclair of Ulster, with the above title.

St. Andrew’s Bridge: John Gantz

Painted in 1821 by the Austrian father of Justinan. He worked with the East India Company as a draughtsman and architect. Later, father and son opened a publishing house.

Suspension Bridge Chinta�dri�pettah: An artist’s sketch showing the imported suspension bridge that crossed the Cooum at Chintadripet in 1831.

|