Abraham Eraly – a much loved Editor and a greatly

respected writer of the historical

In the week following the announcement of Abraham Eraly’s death, the most heartfelt expressions of condolence were posted on the web and came from writers and journalists whom he had nurtured as Editor of Aside, the erstwhile city magazine that was Madras’s unique voice.

There was reason for this. Every one of those who fondly remembered Eraly did so because he or she felt each of them owed a debt of gratitude (big or small) to him for his undeniable part in letting every one of them discover their strengths and weaknesses as writers. I use the word ‘writers’ intentionally; the biggest strength of Aside, even when it was reporting news, was the fine quality of its writing.

A lot of people know of Eraly as a historian, a man who had both taught history and written on it (nine delightfully written books on Indian history that sadly received more appreciation abroad than in India). But he was also many other things, an artist – Aside probably carried the only serious writing among Madras journals of the time, on contemporary art and artists; a collector of art – there was an enviable amount of art on our office walls; a man with a great sense of design and aesthetics in printing; a good photographer; and a stickler for detail.

During his editorship (and this was when the magazine was at its best), Aside explored Madras the way no other publication had ever done before. Its writers examined its spaces (the inner and outer), its people (however staid or outlandish), its language (does anyone remember R.Parthasarathy’s enchanting piece, ‘Summa I came’), and its spirit, in a tone that was astute, often irreverent, sometimes critical, and always soft, just a little above a whisper. Hence the magazine’s name. As asides enhance or dispute the statements they are attached to, the magazine’s writing qualified the character and voice of Madras.

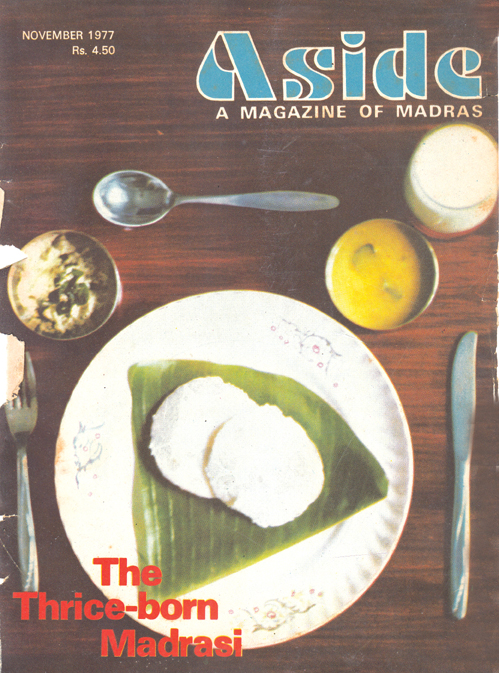

The cover of the first issue of Aside, November 1977.

I have an image of our working environment that is sort of frozen in time, around mid-morning. Eraly stands, arm draped over the top of a cubicle partition, saying, “It definitely needs rewriting, rethinking even.” He is referring to a manuscript that is liberally overwritten with the editor’s red ink. The writer in question responds by throwing a minor fit – “That is probably some of the best writings I have ever done!” “You can do much better!” replies Eraly before turning to greet a visitor. This could be anyone – S. Muthiah, having come to offer an article or some advice, or Rom Whitaker, suggesting the government should start a corporation for selling rat meat (“It’s good protein, available in plenty, and we will be saving the crops” was his argument), or a white skinned sadhu named Ishwar Saran throwing a tantrum because we had changed a comma in his copy. Photographer S. Anwar, holding up a black and white stunner of a picture of a Bharata Natyam dancer or K.V. Anand extolling the virtues of the fish-eye lens that he had recently procured and that he had absolutely decided to use it for our next cover photo. Kavitha Shetty, drinking tea and observing, “I think T. Rajender is cute! Can anyone else rhyme so ridiculously? Besides, I love his beard and moustache.” Sridevi Rao fluttering her beautiful fingers as she says, “There is life after death, I am sure of it.”

Ira Bhasker or LR. Jagadeesan was informing us that all Tamil politicians and almost all Tamil film stars hated us because we poked fun at them. In other words, it was a picture of an office hard at work.

At Aside, there was no real hierarchy in the office set-up. It was not just because it was too small for any real pecking order, it was also because Eraly firmly believed that people working together performed better than people working for someone. He created an office environment that encouraged creativity and discouraged mundaneness. Staffers from that time recall with relish how, for Eraly, form was as important as content in writing. The elegant turn of phrase was as precious as honest reporting. And when appreciation for your writing came from him, it was always special, not because it was from the boss but because it was from someone who wrote so well himself.

As a writer, Eraly was entirely self-driven. He was a curious man, in the best sense of the term. He inquired into facts and issues with a clear and logical vision and was willing to consider the most seemingly outrageous presumptions until they crumbled under his scrutiny. A known atheist (“I have been unsure of many things in my life,” he liked to say, “but there is one thing that I am absolutely sure of – that there is no God.”), he was still willing to explore, in print, every spiritual possibility, from transcendental meditation, life-after-death, the most extreme forms of astrology and the wackiest of Godmen.

Although he liked to say that he gave up teaching history because his job had begun to resemble ‘premature retirement’, the historian in him never really vanished. “To understand what we are, we have to go back and understand what we were,” he reasoned. Most major Aside articles were therefore divided in three parts, one of which invariably studied the history of the issue or the person in question. No prizes for guessing which one the editor wrote. Incidentally, there was always some curiosity about the aliases Eraly used for writing in the magazine. Abraham Eraly wrote editorials and conducted major interviews; Ashok Dorairaj wrote on ticklish issues and took photographs; Pratibha Iyer penned those biting and, often, hilarious reviews.

It was Eraly’s personality that attracted to Aside (especially in the early issues) some remarkable talent. The contributors included Harry Miller, S. Muthiah, R. Parthasarathy, Sadanand Menon, Rathindranath Roy, Mithran Devanesan, S.G. Vasudev, Ajit Ninan – the names often read like a list of Madras’ who’s who. Every issue was a joy to create and design and the result was an unusual treat for the Madras reader hitherto fed on a diet of plain reporting and conservative writing.

It was only when, because of commercial constraints, Aside turned into a ‘news fortnightly’ that the magazine lost its unique charm and with it, perhaps, the interest of its editor. Still, by that time, Aside had already achieved what Eraly had intended it to – help to understand the city a bit better by exploring its past and present in depth. The legacy Abraham Eraly has left behind is that of original thinking and great writing. Of how many can that be said?

-Janaki Venkataraman

|