|

Among the buildings across from the Marina, the most historic and still very striking – at least the part that can be seen – is Chepauk Palace, which belonged to the Nawabs of the Carnatic until the Government dispossessed them of the property in 1855. Chepauk Palace and gardens were eventually bought by the Government in auction for Rs. 5,80,000 in 1859. Since then, it has mundanely housed ill-kept Government offices!

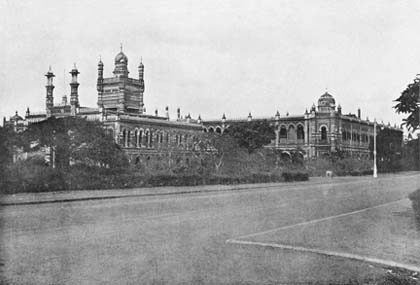

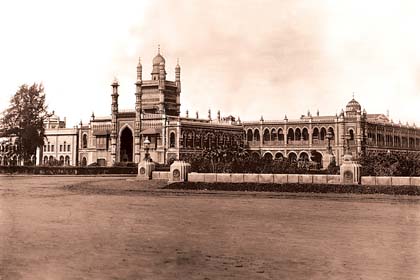

“On the death of the last Nawab of the Carnatic, this fine old palace (above), built in the Moorish style, became Government property and was occupied as the Board of Revenue Offices” – Willie Burke’s picture and words in the late 1920s, and below Klien & Peyerl’s picture (Courtesy: Vintage Vignettes) of Chepauk Palace in the first decade of the 20th Century.

|

When Day acquired his Madras, all the land around his acquisition was part of the Vijayanagar Empire’s Carnatic. But, as the Mughal Empire disintegrated, the nazims of the Carnatic, who had defeated Vijayanagar, became a law unto themselves and the feuds between the nazims of the Deccan and the Carnatic (more or less the present Tamil Nadu) led to the Carnatic Wars, with the French and the British backing rivals.

British triumph led to Muhammad Ali Wallajah becoming the Nawab of the Carnatic (1749-1795), whereupon he sought a permanent residence in Madras, preferably in Fort St. George itself. Instead, it was suggested that he build it under the protective shadows of Fort St. George. Chepauk Palace – some say designed and built by Paul Benfield, a Company engineer always in trouble till he quit and became a building contractor, and who later acquired international notoriety as chief moneylender to the Nawab, an activity that, in retrospect, helped land the Carnatic firmly in the lap of the British and set them on the course of empire – was the outcome in 1768. It was this palace that undoubtedly pioneered the Indo-Saracenic architectural style, later followed by ‘Mad’ Mant, Robert Chisholm, Henry Irwin and others and which culminated in Lutyen’s and Baker’s New Delhi.

The Palace, added to over the years by others, comprises two distinct blocks that were a hundred years later linked by Chisholm with the distinctive tower, symbol of imperial power, that now soars over them. The northern, single-storey block was Humayun Mahal and a part of it was the soaring two-storeyed Diwani Khana (Durbar Hall). The southern block, the Khalsa Mahal, is two-storeyed and smaller domed. By 1770, the Palace grounds were 117 acres in extent.

Robert Chisholm between 1865 and 1870 added to the Humayun Mahal’s southern and eastern sides, particularly to the Diwani Khana, rooms, verandahs and arches, and created the Revenue Board Office which is what is now visible from Wallajah Road. He also added a square, two-storeyed entry building to the east of the amalgam he had made of Humayun Mahal and linked both with a carriageway. The addition, with a high arched entrance and tall corner turrets, is called the Records Office but, when created, it was a spectacular new entrance – now from the east – to the complex. Near it was raised architecturally characterless Ezhilagam in the 1960s for Government offices.

In its heyday, the grounds of Chepauk Palace stretched from what is now Bell’s Road to the beach, from Pycroft’s Road to the Cooum River! Indeed an area in which elephants once stabled within the grounds. The whole area was surrounded by a wall with the main entrance on the west, a massive triple-arched gateway located on Wallajah Road, near where the canal was later dug. Music once used to be played every evening from the top storey of this Naubat Khana.

Alleged treason on the part of the Nawab Umdat-ul-Umrah, Wallajah’s son and successor, who was accused of conspiring with Tipu Sultan, led to the second Lord Clive sending in the troops to occupy the palace in 1801 after the death of the Nawab. The annexation of the Carnatic (from the Nellore to the Tirunelveli Districts) followed and so did the abolition of the ‘Nawabocracy’. Instead, a Titular Nawab was created, and when the last Titular Nawab, Ghulam Ghouse Khan Bahadur, died in 1855, Government made plans to make its occupation permanent. The auction of the Chepauk property followed, Government alone being able to afford it.

The annexation of the Carnatic in 1801 – and all India followed – was a sequel to the Government undertaking to liquidate the Nawab’s Carnatic Debts (Benfield was the largest creditor!) in return. Muhammad Ali’s public debts were estimated at 3 million pagodas* and his private liabilities at 7 million pagodas. After the annexation, further private claims amounting to nearly £ 30.5 million were proffered, but nearly £ 28 million of them were thrown out as false or fraudulent!

Much of Government Estate was part of the vast Chepauk estate of the Nawabs, who were finally left with only the right, granted by the British, to be called ‘Princes of Arcot’. Pensions amounting to about Rs. 150,000 a year were also paid to the Prince in office and certain relatives from 1868. Successive Governments of India to this day respect these treaty obligations. In 1870, the British gave the Arcot family Amir (Arcot) Mahal, at the western end of Pycroft’s Road, a striking building built in 1798, but it was not used by the family till 1876.

When the Nawabs of Arcot were made the Amir-e-Arcot in 1868 by Queen Victoria, they were also granted a political pension (the ‘Carnatic Stipend’). That pension of Rs. 14,000 a month, income tax exemption of Rs. 24,000 (both as increased in the 1920s) and vehicle tax exemption, all continue to this day. Protocol ranks the Prince of Arcot with a State Cabinet Minister, grants him a full police escort, and allows him use of his royal crest and flag. Arcot is one of the four princely families still recognised by the Government of India with a pension, the

others being Tanjore, Calicut and Oudh.

The splendours of the palace are now hidden by later constructions, some of which took their architectural cue from the Indo-Saracenic design and gave Madras a distinguished skyline that existed well into the first half of 20th Century, and more recent ones that reflect the aesthetics of modern Public Works Department architecture and are incongruous. In what were once the gardens of the palace, the Nawab’s Artillery Park from where gun salutes were fired to greet visiting dignitaries, and the Nawab’s octagonal bathing pavilion by the Cooum, there came up the University buildings. In the southern gardens, there was integrated. the new Indo-Saracenic building for the Public Works Department in 1866-67, Robert Chisholm creating the design. And adjoining it, further south, was built Presidency College, where the Nawab’s Courts of Justice used to be.

* A pagoda is about Rs 25 today; £1 about Rs 80. In those days, a pagoda and a pound were about the same, Rs 10.

|