|

Steam engines have always caught the imagination of the young and old alike. These locomotives were so awe-inspiring that their sheer presence made the drivers stars in their own right. The engine driver was revered as he was the interface between the passengers and the organisation. Old timers along the Tiruchirappalli-Villupuram stretch still vividly remember two such drivers, Gerard Vanhaltren (72) and Rudolph Jeremiah (73), superstars of Southern Railway’s Tiruchi division for almost 35 years.

Gerard Vanhaltren ...

Tall and lanky Gerard Vanhaltren, a descendant of Dutch immigrants who came to India in the 18th Century and made Nagapattinam in Tamil Nadu their home, joined the Railways as part of his family tradition. His grandfather, Aliek, was the driver of a Mail train in Tiruchi division, while father Alfred was a master technician at Tiruchi’s Golden Rock Workshop. “That was the tradition. If you were born in a Railway colony, you joined the Railways as a fish takes to water. It was an unwritten rule,” reminisces Vanhaltren, now leading a retired life at Crawford Colony in Tiruchi.

Once he completed schooling, Vanhaltren appeared for the Railway Service Commission Examination. “I was appointed as apprentice Fireman in September 1963 when I was nineteen. The training was really tough. You needed to be physically and mentally fit to undergo the gruelling schedules. But they helped me develop my willpower,” narrates Vanhaltren.

He was promoted as shunting driver in 1968, underwent advanced training in diesel locoomotives and successfully completed the tough LM-16 (Loco Mechanism) programme. “Only a hardy man could become a steam locomotive driver. These locos were open on all sides and you were exposed to the elements of nature; the scorching sun of the summer or the heavy downpours of the monsoon. You had to monitor all kinds of parameters while operating the steam locos – the water level in the boiler, the quantity of coal which had to be shoveled into the firebox, the speed of the train, signals and, of course, the gradients. It was thrilling because you had to think on your feet all the time and find solutions midway. You had to be an all-purpose man,” recalls Vanhaltren, his skin still tanned by the heated furnance. “I can feel the coal dust in my mouth. And my lungs still have some sooty carbon content”, he adds.

Steam loco drivers turn rough and tough because of the nature of the job and the temperature inside the engine. “There was no room for bantering and soliloquies while on duty. When we negotiated curves and gradients, our minds had to be at their sharpest and work in sync with the engine. An eye on the water level, another eye on the quantity of coal and both eyes on the signal towers... That’s how steam loco drivers worked,” he relates.

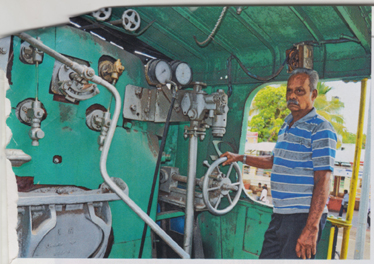

Rudolph Jeremiah, both remembering the past.

Vanhaltren did not have a single accident in his 38-year career. “But there were occsional failures due to other factors. Once I was hauling a 1,000 tonne train on the Villupuram-Tiruchi route, known for its steep gradients. It was raining all the way from Villupuram. We have to maintain a particular level of water in the boiler. Any increase or decrease in the levels would melt the lead plugs which provide the heat to boil the water. We crossed Virudachalam at 10 in the night. The rainfall increased as we moved forward. The entire coal stock in the tender box got soaked. Once the required quantity of coal could not be fed to the fire box, the pressure started dropping. This resulted in the lowering of water level, fall in pressure and steam. The lead plug melted and the train came to a halt at the top of the gradient. Meanwhile, the Rockfort Express for Chennai left Tiruchi at 10 p.m. and was on its way. The route was yet to be doubled. There was no way to communicate with the guard or with the nearest station,” recounts Vanhaltren.

All of a sudden the train started moving back because of loss in pressure. Since there was no pressure, the brakes too could not be applied. But the train came to a halt as the momentum slowed and Vanhaltren took to his legs and made it to the nearest railway station. “Luckily for us, the station master of one of the halts which we were supposed to cross after Virudachalam noticed the delay in our arrival and alerted all the nearest stations. The Rockfort Express was blocked at one of these. Normalcy could be restored only after the arrival of a relief engine from Virudachalam,” he says.

Petharaj, a former station master, who was an ardent fan of Vanhaltren, remembers the incident with mixed feelings. “It was Ger’s (as Vanhaltren is called by friends) presence of mind which saved the day. his devotion and dedication could be seen by the speed with which he made to the nearest station in the rain as there were no modern communication facilities.”

The station master also remembers how daily commuters would ask him who was the engine driver for the day. “The moment I mentioned Vanhaltren, they would nod their heads in appreciation ‘Today we will be on time,’ they used to say.”

Amalraj, a retired electrician of the Southern Railway, who is an avid buff of steam locomotives, explains the reason behind the expertise of Vanhaltren. “He had magic fingers. The smoothness with which he brought the engine to life and gently took it forward was something to be experienced. There was no jerk or jolt and the ride was a smooth affair. Whether it was steam locos or diesel engines, Vanhaltren made a big differnece,” certifies Amalraj. And the man himself says of his art, “I treated the engine like a human, tender and soft.”

* * *

Life has not changed much for Rudolph Jeremiah who bade farewell to Indian Railways in 2000 after working for 28 years as a steam loco driver before switching to diesel engines. What is unique about Jeremiah is the kind of passengers who had boarded trains hauled by him. Jeremiah was in command of the Prime Minister’s Special Train which took Jawaharlal Nehru from Villupuram to Neyveli for the commissioning of its thermal power plant in 1963.

Jeremiah, who joined the Railways as an apprentice fireman in 1962, followed the foot-steps of his father Frederick who was a special engine driver with the Railways.

An engine driver’s job was demanding, says Jeremigh. “After 12 hours of hard work in a steam loco, all that you want is a bath and sleep. You wake up all refreshed and energised for another grilling schedule,” he adds. Like Vanhaltren, Jeremiah too almost had a soul connect with his engine. “The moment I entered my cabin, I would go into a trance. Nothing else crept into my mind. I became a part of the engine as much as the engine became a part of me,” he relates.

Balasubramanian, his colleague and a shunting driver in Tiruchi, describes Jeremiah as a troubleshooter par excellence. “He used to attend to even major faults and repair works in the engine all by himself. I remember an incident which happened at Mayiladuthurai. We were about to leave for Tiruchi when the Piston Gland Packing (PGP), which prevents the steam from escaping from the boiler, collapsed. Though Jeremiah approached the maintenance staff for help, they asked him to wait as they were attending to another job. So he tinkered with some instruments and got a new PGP ready in minutes.

“The train left the station on time and reached Tiruchi as per schedule. Had we waited for the maintenance staff to attend to the fault, we would have been delayed by at least three hours,” recalls Balasubramanian.

Jeremiah, who has a passion for all kinds of electrical and mechanical instruments and gadgets, says he was honoured by the authorities the next day in Tiruchi. But the senior engineer told him, “We know your passion for punctuality and discipline and at times you may have to make some compromises.”

Like Vanhaltren, Jeremiah too was very much in demand. “When passengers saw me, they would raise the thumb of the right hand as a sign of acknowledgment. Trains hauled by me never lost a single minute during running hours,” remembers Jeremiah.

He regrets that the Railways has completely phased out steam engines from service. “I can understand they are not eco-friendly. But the steam locos are the one and only link we have with the earlier days of the pioneers. We could have maintained them in museums and have short runs for visitors as a piece of living heritage,” he suggests.

These days, he and Vanhaltren keep memories alive by walking to the Tiruchirappalli Railway Junction museum to look at the exhibits and re-live their past. (Courtesy: Anglos in the Wind)

|