|

A 300-year-old map of Madras shows about 250 reservoirs, over 70 temple tanks and three freshwater rivers which are now forgotten. The shoreline of the Bay of Bengal in Madras was made up of long beaches and lagoons.

Madras that is Chennai is a crowded city, baffling in its diversity and a place where tradition and modernity co-exist. Travel a few kilometres and you can find rural pockets, complete with mud roads, thatched huts, wandering cattle and ancient temples.

The first British warehouse came up in 1639 when the British acquired the sandy beach from the local nayaks on lease. It was situated between the Elambore River on the west, the Bay of Bengal in the east and the Cooum River in the south.

In 1700, the Cooum River and the Elambore River were linked to equalise the flood waters.

In 1800, the city was divided into eight divisions. The laying of the first railway line and the building of Royapuram station in 1862 induced people to move northwards and settle near Royapuram.

Before 1800, the roads were in a radial pattern, but after 1810 ring roads were developed inside the City. This was the first phase in changing Chennai’s landscape. Many public buildings were constructed fronting the beach in the early 19th Century.

The important developments during the period 1901-1941 were the commissioning of the electrified suburban metre-gauge railway between Beach and Tambaram in 1931, which gave a fillip to the development of the suburban areas as far as Tambaram.

The thirty years between 1941 and 1971 saw a tremendous growth in population and economic activity in and around the City and thus many nagars came into existence.

Forest resources

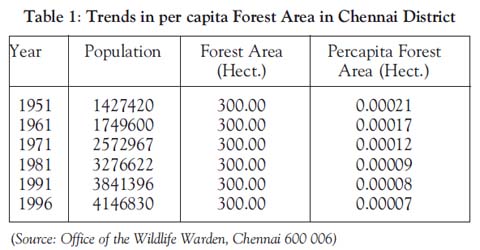

Chennai district is not endowed with many forest resources except the Guindy National Park, a Reserved Forest about 270 ha in extent. Besides its forest vegetation, different water plants are seen in the lakes and ponds inside the park. The per capita forest area in the district has declined from 0.00021 hectare in 1951 to 0.0007 hectare in 1966, which is mainly due to population growth (Table 1).

Urbanisation

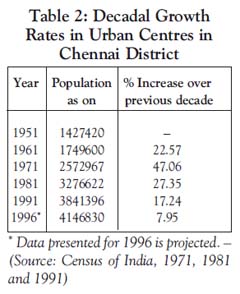

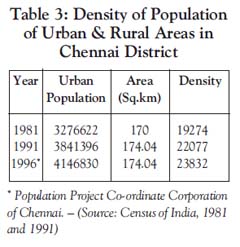

Chennai is almost 100% urbanised. However, the annual growth rate of population had declined from 2.6% to 1.7% between 1961 and 1991. But the increasing total population without commensurate increase in the city’s municipal area led to an increase in congestion, overcrowding, steady growth of slums and squatter settlements and a heavy strain on the infrastructure and services in this area. The migration from neighbouring and other districts in Tamil Nadu for employment opportunities has put pressure on available land, increasing the overall density from 19,270 persons/sq.km to 23,832 persons/sq.km between 1991 and 1996. The decadal growth rate of population shows the maximum during 1961-71, beyond which the decadal growth percentage records a decreasing trend (Table 2).

Slum population

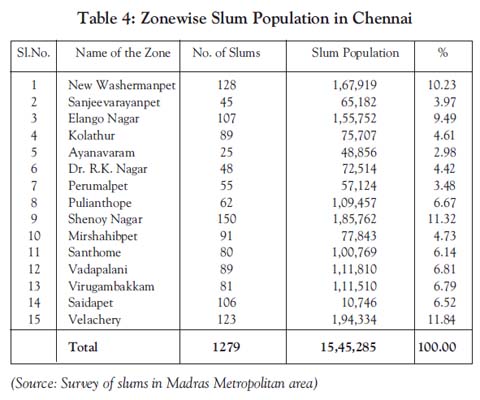

Chennai City has a slum population of 16.41 lakh spread over 1279 slums. The percentage of slum population to the total population in 1981 was 22.13. This has increased to 40.39 per cent in 1996 (Table 3). Most of the slums in the city are of linear type, located along the waterfront (i.e. banks of the Adyar River, Buckingham Canal, Cooum River and Otteri Nullah) and along the roadside. The zonewise slum populations of Chennai are listed in Table 4.

The maximum changes in the landscape of Chennai are to be seen in New Washermanpet, Velachery and Shenoy Nagar. These are registered slums with a population of about 34 per cent of the total slum population in the city.

The slum families living on the banks of rivers survive without any basic facilities and are subjected to annual flooding. They also pollute the water courses.

Population density, 2001

Chennai has a large migrant population, which mainly comes from other parts of Tamil Nadu. In 2001, out of the 937,000 migrants (21.57% of the city’s population), 74.5% were from other parts of the State, 23.8% were from rest of India and 1.7% was from outside the country.

Lakes

Chennai and its suburbs once had over 250 small and big water bodies that were used for irrigation and drinking water. Today, the number of water bodies has been reduced to 46. These 46 water bodies are also slowly being encroached on. The remaining water bodies have been filled up and developed into government offices, roads, bus stands, industries, colleges, memorial parks, railway road and dumping yards. Besides the water bodies, temple tanks were also used as a water source. Only about 50 temple tanks still exist in the city.

Conclusion

Chennai’s landscape is changing fast, as old buildings are being demolished and converted into multi-storeyed apartments and information technology parks. From a single house, the concept has changed to hundreds of houses in a single place. The development of townships and roads has encouraged the large-scale migration of people from other districts of Tamil Nadu and from other States in India. The impact of urbanisation on land use is felt widely.

On the one hand, the spatial expansion of urban centres brings more rural area under the urban administration. On the other hand, land use within the urban centre undergoes various changes such as population pressures and large-scale internal migration, which has resulted in the rapid conversion of wetlands, riverbanks and other wastelands all of which have caused serious ecological and environmental problems. (Courtesy: Eco News, journal of the C.P.R. Environmental Education Centre, Chennai. )

|