|

No other State in India has a continuously evolving tradition of painting as Tamil Nadu has. Prof. Job Thomas’ book on paintings in Tamil Nadu* takes the reader through ancient paintings down to paintings in the colonial and post-colonial period and provides a wealth of information on them.

An example of ancient rock art in Tamil Nadu. |

500 BCE seems to be an agreed-upon date for some of the earliest examples of rock art in the State, with the paintings in Konavakkarai, Karikkiyur, Kilvalai, Mavadaippu being some of their locations. The paintings are of men and animals. However, Prof. Thomas’ list of rock art sites seems very brief compared to the actual one. Several references to paintings also abound in Tamil literature from 100 BCE to 500 CE. Some of these were in temples, on walls. Others were on cloth, even canopies, over royal beds or worn by royalty and nobility.

Pallava paintings (600-750 CE) are examples we can still see in places like the Kailasanatha temple, Kanchi, and the Talagiriswara temple, Panamalai. These paintings give us a sense of the textiles and the adornments of the period. Their fluid lines and light and dark shading are testaments to the expertise of the painters who used fine brushes and painted on wet plaster before it dried out.

Pandya paintings (650-750 CE) can today be found only in the Jain cave at Sittanavasal. The subject is of devotees gathering lotus flowers in a pond teeming with wildlife. Here again, the expertise of the painter is manifested in his keen sense of reproducing nature in all its splendour.

From Chola times (850-1200 CE), the best examples are in the Brihadeeswara temple. The painter’s mastery of line and colour is obvious. Lines are rendered confidently with razor-sharp crispness. Colour is balanced and pleasing. Nonetheless, compositions are based on canons of sculpture rather than of painting.

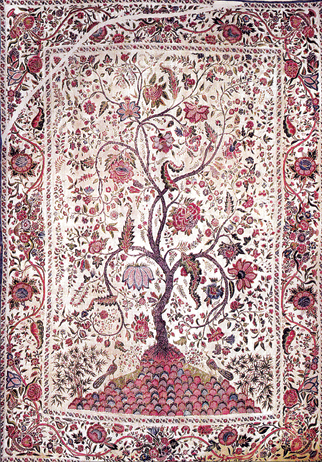

Company paintings – Kalamkari design. The traditional Indian Kalpavriksha with modification to suit European taste. |

In the Vijayanagara period (1350-1550 CE) and in the Nayak period (1550-1650 CE) the change of political climate dictated the style of painting. Sponsorship became localised. After the Muslim invasions, many structures were being built at the same time and painters were in a hurry to complete their work. Very often, they were local experts who would not have travelled, so local motifs began to dominate and religious stories became more important. Paintings, therefore, became serialised with many squares, as in a comic strip, the story told in text at the bottom. Colours became more earthy, details less elaborate and lines thicker and more quickly drawn. Tiruvellarai, Chidambaram, Tiruvalanjuli (since destroyed by later renovations), Pattiswaram, Tirumalai (near Vellore), and Tiruparutikunram have some examples of these styles. But Thomas’ lists of temples with important Vijaynagar/Nayak paintings have glaring omissions – Srirangam. Azhwar Tirunagari, Tirupudaimarudur and Ariyakudi, for example.

Maratha paintings (1700-1850 CE) began to show a greater Western influence. Paintings now became not only religious in nature on temple walls but royal portraits were also done to frame and hang on the walls of palaces or given as gifts. Thanjavur paintings, as we know them today, became more popular in the reign of Saraboji II. In fact, Alagiri Naidu, the painter who taught Ravi Varma, lived in Tanjore till the kingdom was annexed by the British in 1856. But there is a rather patronising dismissal of the Maratha contribution to temples.

2.Company paintings – Hand-painted and resist-dyed cotton dress – chintz. |

Many paintings on paper and on board with cloth and gold foil were made as souvenirs for the British to take back. Examples of these surface occasionally in auctions and can be seen in museums in England and Europe. They were called ‘Tanjore Moochy’, as the paintings were done by the Muchi caste whose members also painted leather puppets. Influenced by the West, paintings of the royal patron began to be more realistic, and focussed on the accuracy of the sthula sharira (physical presence and likeness) of the subject rather than on the sukshma sarira or the spiritual body. This meant that portraits began to resemble conventional posed representations with Western backgrounds of curtains, chandeliers, etc.

The last two chapters look in depth at the paintings done during the East India Company days (1600-1850 CE) and in the Colonial period (1750-1950). The absence of commissions made it lucrative for weavers and painters to take up work from the East India Company. It worked well for the Company as well, as in India they had to exchange expensive gold and silver for the Indian spices they wanted. Textiles purchased cheaply in India could be bartered in Indonesia for pepper that was much more expensive in India. In 1608, cloth purchased in Tamil Nadu for £5000 could be bartered for Indonesian pepper worth £20,000. Thus, by 1650, the economies of England, Holland, India and Indonesia began to be tied together. In this game, Indians were at a disadvantage, being less inclined to view trade in impersonal profit-loss and military terms.

Painted textiles, or those dyed in indigo blue, were high in demand and as the Coromandel coast became a hub of preference, Francis Day found it easier to negotiate for a site and found Madras in 1639. The location was chosen as “it was the only place for paintings desired southwards.” Southwards was Indonesia and paintings were those done on cloth. Indonesia prized Batik cloth that, for reasons of intricate patterns, could even take a year to produce. The same, or a more delicate effect, could be achieved through Kalamkari from the Coromandel in a much shorter time and, therefore, the latter became a commercial hit in Indonesia as well as in Europe.

What started off as curtains and bedspreads soon grew to clothes as well. The incredible popularity in Europe meant a transfer of European motifs as well. The Scandinavian Tree of life acquired an Indian touch and textiles were made in such a way that the designs looked better when the bolt of cloth was actually stitched. Block printing combined with Kalamkari pen-work made the process faster. Sadly, in this chapter, though we have photos of these textiles, we have no photos of temple paintings like those in Azhwar Tirunagari where Gods are shown by 19th Century painters wearing such textiles.

Bitter relationships between the Indian painters and the Company’s merchants were not uncommon. Of note is an instance in 1680 when painters ‘struck’ work, protesting against Company agent Streyensham Master’s orders. By the end of the 17th Century, the producers created two kinds of painted cloth. The better and finer workmanship went to Britain and the inferior to Indonesia. Also in demand was painted cloth for tents. The market for Indian cloth became so popular that textile merchants in Britain complained and, in 1701, heavy tariffs were imposed on Indian textiles and the trade was crippled. A small batch of kalamkars was supported just to keep the art from extinction.

As was the ancient Pallava and Chola custom, Collet Petta and Chintadripet were created to settle colonies of painters and cloth-makers. The villages survive as part of Chennai today.

By 1800, the Company had changed the power dynamics. The old courts and temples had been reduced in power and the new generation of patrons were not always endowed with an aesthetic sense. While Tamil Nadu’s artistic traditions stagnated, it became closer in copy to the increasing number of British oil painters who began visiting India for lucrative commissions from Indian rajahs and British officials. Between 1769 and 1820 nearly 60 British painters arrived in India. British education and media also had their influence on the local painting style, since more and more British were living across the length and breadth of Tamil Nadu. In 1850, an art school was opened by Dr. Alexander Hunter to produce artists “Indian in colour, European in taste.” The British – A.J. Arbuthnot, for example – thought the Indian artists lacked “inventive faculty” and were not happy with Hunter training his students in the higher forms of painting.

Hunter and his successors persisted and what eventually became the Government College of Arts and Crafts had students, with Government support, learning how to do botanical water colours and paintings that had Western notions of perspective, depth, dimension and mass. By 1890 and onwards, the College began to attract Bengal artists as well. They came with their own styles. The creation of the lithograph press marked mass marketing of prints.

The founding of Kalakshetra in 1936 was an important event, since it was a move by Indian intellectuals, many of them Theosophists, who wanted also to return to Indian artistic traditions.

Post-independence, the Lalit Kala Akademi has been an example of Government’s commitment to the continuous tradition of painting in the State. Not mentioned in the book, but worthy of recall, is the work of S. Rajam. The creation of the Cholamandal Artists’ Village in 1966 also signalled an awakening of artists to the need of marketing their work.

The postscripts deal with historical information of some of the dynasties and literature and there is a welcome note on the biographies of some famous writers on art or those who discovered/catalogued some of the paintings mentioned in the chapters.

The book’s strength is in its East India Company and colonial chapters. It is also rich in black-and-white and colour illustrations, the latter in their numbers fitted into 32 pages. The rock art illustration used here is from the cover of the book and the other two illustrations are from those 32 pages.

Pradeep Chakravarthy

Pradeep_Chakravarthy@infosys.com

* Paintings in Tamil Nadu – A history by I. Job Thomas (Oxygen Books, Madras).

|