Film studios need land by the acre to function. In the beginning of the 1930s, things were more complicated – the technology of the time allowed only live sound recording, so the location had to be chosen such that noise interruptions like traffic etc. had to be minimal. The Chennai of those days was largely confined to dense localities like George Town and its neighbouring areas. Beyond that, there were small villages of groves and garden – namely, Teynampet, Adyar etc where the studios were established. It can be understood that studios paved the way for the expansion of Chennai city. In this article, we will see details and new research-based information about the talkie studios that functioned from 1934 to 1939.

The importance of film production studios

Film studios have played a significant role in the development of cinema, and are a crucial subject when discussing the history of the silver screen. After the advent of talkies, studios served as the single production unit that made films from scratch to completion. In the 1930s and 40s, a studio’s name was included when advertising the release of a film. Studios of that period were massive set-ups. Most of the films shot in the first twenty years or so of cinema were grand epics and legends; so studios had to plan many factors including the expansive stage sets, myriad costumes and more. It was common for studios to employ a large number of permanent workers.

Before 1934, it was necessary to travel to North India to make talkies. Studios were then established in various towns in Madras Presidency. An analysis of the pioneers behind these efforts, and the towns in they chose to set-up studios can offer a fair indication of the social circumstances prevailing at the time.

In the first twenty years, South Indian studios employed film professionals from Northern and Eastern India as well as overseas, as they were well-trained. Many workers from Madras Presidency learned the craft and technologies involved from these skilled experts. Studios provided these aspirants with such an opportunity.

Not only did studios do away with the necessity of travelling to North India to shoot, they also improved the rather poor quality of locally produced films. They flourished so well that Hindi films began to be made in Madras. Why, even the credit for blazing a new trail in Sinhala language films goes to studios in Madras Presidency!

Talkie cinema halls

In those days, Kilpauk and the surrounding neighbourhood formed the centre of the film industry. These areas have been home to many studios since the silent film era. Initially, films were shot without the facility of electric lights and had to rely on sunlight. So the direction and layout of a studio were planned in such a way that a shoot could avail sunlight throughout the day without being impeded by shadows. The early history of Tamil cinema records that films were made with great difficulty till 1936 – shooting had to take place when the sunlight was plenty and bright, and come to a halt when the light was low. Back then, there were no transport facilities to commute to studios located in areas like Adyar and Vepery. People had to travel on foot, and rarely used vehicles like cars and jhutkas.

Everyone at a studio worked together as equals in a family. There was no discrimination. They identified the tasks that had to be completed and worked as much as they could without a break. In those days, the prevailing custom was to stay in the studio until a film was wrapped up. Sets and other equipment put up in a studio were made use of for a very long period. So it was not unusual to see these setups in many films.

Since film reels were highly flammable, studios back then carried a high risk of burning down. There are many stories of such studios being lost to fire, an example being R. Nataraja Mudaliar’s studio which had the distinction of being South India’s first studio. When talkies appeared, the number of exterior shots began to diminish, and entire films were shot inside the set.

Srinivasa Cinetone

It is common to see the words ‘tone’ or ‘sound’ appended to the names of studios and companies that produced talkies, which had to synchronize a film’s sound and visual.

A. Narayanan worked in the film industry as a sales representative for silent films and related equipment through the company ‘Exhibitor Film Service.’ He also produced and released silent films through a studio and film company called ‘General Pictures Corporation.’ When talkies appeared, he established a film production company called Srinivasa Cinetone, named after his son. He is also credited with setting up Sound City, the first studio in South India with the facility to produce talkies. Sound City was established on 1.4.1934. (Many people tend to confuse Srinivasa Cinetone and Sound City; however, records show that the Srinivasa Cinetone was established before Sound City.)

Srinivasa Cinetone was located at 107, Poonamallee High Road. The entrance was located on Poonamallee High Road and the back gate was on Flowers Road. A. Narayanan’s wife Meenakshi trained at Srinivasa Cinetone from 1936 and emerged as India’s first female sound recorder. The studio’s first film was Srinivasa Kalyanam which was released on June 30, 1934. Since the crew consisted of talent only from South India, it can be said that this film was a truly South Indian production.

A. Narayanan, R. Prakash, T.C. Vadivelu Nayagar, and Ramkumar (a.k.a The Man of a Thousand Faces) were the film’s directors. T.V. Krishnaiah was the cameraman. R. Prakash had trained abroad and was already experienced with producing silent films in his studio, so he was well-versed in cinema techniques. He contributed greatly to all work related to the film’s production.

Apart from the films of his own company, A. Narayanan made Srinivasa Cinetone available to shoot films made by other production companies as well. Unfortunately, none of the films made by A. Narayanan saw much success. The reasons appears to be two-fold – one, he shot these films in a very short period of time, sometimes as little as ten days; two, the studio lacked adequate facilities. In fact, the crew had to use a hand-held camera to shoot the first couple of films.

Jayavani Cinetone

When A. Narayanan sold his silent film studio at Tondiarpet – General Pictures Corporation (GPC) – all the equipment was purchased by A. Seshaiah. He had acted in GPC’s silent films and had received training in film direction. He directed the talkies Ramayanam and Savitri, which were released during the period 1932-33. The studio Jayavani Cinetone was founded by him and a few others.

The film Dasavatharam which was released in 1934 was shot at Jayavani Cinetone which belonged to Jayavani Films in Tondiarpet. It was the first film in India to have been produced at a native sound recording unit called Boopathi Sound System, which was established by an engineer named Boopathi Nayagar. He ran a Chennai-based college for sound recording.

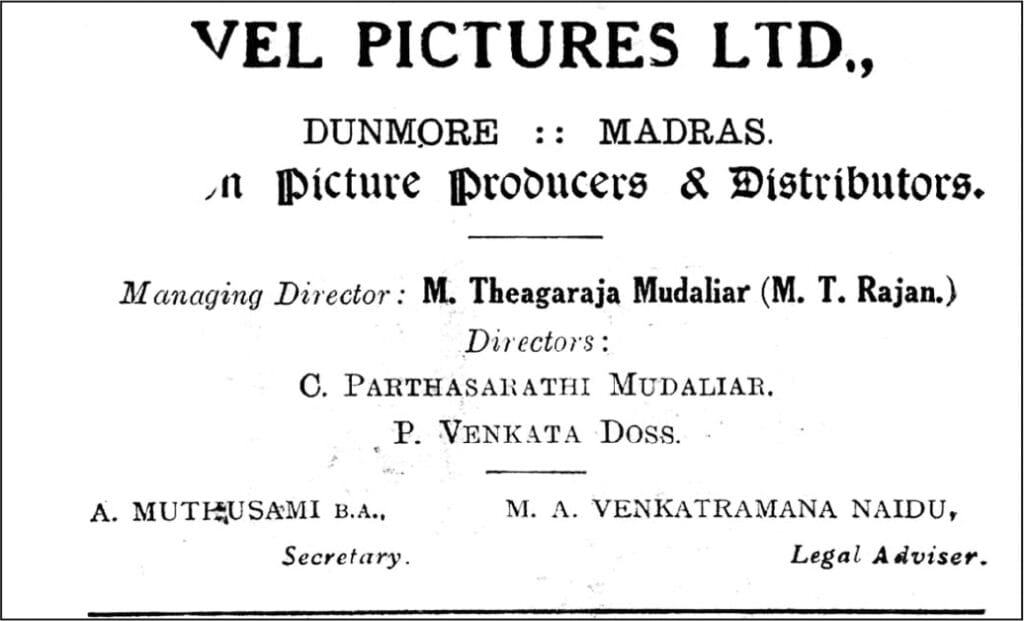

Vel Pictures

Vel Pictures Studio was established around the same time as Sound City. It later had an inauguration ceremony as well. It was set-up on 21.06.1934 at Dunmore House at Eldam’s Road, Teynampet which was once the Pithapuram Maharajah’s palace. The technicians who worked there were art director O.R. Embarayya, sound recordist C.E. Biggs, cameramen E.R. Cooper and D.T. Telang, lab manager Rudrappa and general manager Rajasigamani Mudaliar.

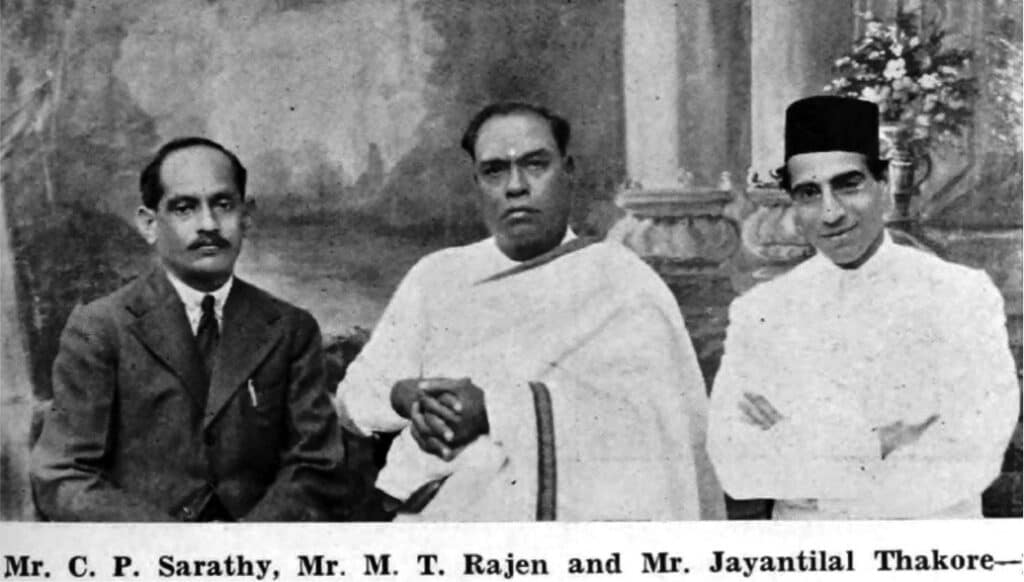

The managing director of Vel Pictures was M.T. Rajan alias M. Thiyagaraja Mudaliar. Even today, there is a small street in Chennai named after him. The partners were C.P. Sarathy alias C. Parthasarathy Mudaliar, P.V. Doss from Krishna district and others.

A group consisting of A. Muthusamy Iyer alias Murugadasa, K. Ramnath and A.K. Sekar went to Prabhat Studio in Pune (at the time, it had relocated its premises from Kolhapur) to shoot Seetha Kalyanam (1934). After gaining some experience, director Murugadasa joined Vel Pictures in the company’s early days along with K. Ramnath and A.K. Sekar. The first film produced at Vel Pictures Studio was the Telugu Seetha Kalyanam.

Murugadasa, K. Ramnath and A.K. Sekar worked on the first three films produced by Vel Pictures – Seetha Kalyanam (Telugu), Krishna Leela (Telugu) and Markandeya (Tamil) – as director, photographer and art director respectively. The trio left the studio in 1934. There are claims that Murugadasa was one of the owners of Vel Pictures, but it is untrue.

Seetha Kalyanam (Telugu) was released on 15.12.1934. Vel Pictures’ fourth film Pattinathar, directed by T.C. Vadivelu Nayagar, was shot in 1936 on a budget of Rs. 31,000. It amassed an unexpectedly huge collection, prompting the studio to purchase land in Guindy as well as a camera worth Rs. 30,000.

The studio shifted premises to Guindy in early 1937. Vel Pictures later became Narasu Studio and came to be owned by V.L. Narasu alias V. Lakshmi Narasimhan, the owner of Narasu’s Coffee.

(To be continued)

Mr. C.P. Sarathy, Mr. M.T. Rajen and Mr. Jayantilal Thakore.