It was the 16th of March, a bright and oppressively hot Sunday, and I had only one thing on my agenda: gallery hopping and for good reason.

As I stepped into the Lalit Kala Akademi, I was taken aback by the transformation of part of the gallery into the ruins of an old, dilapidated hotel room – cobwebs included. This installation accompanied a series of photographs from Nandini Valli Muthiah’s collection titled Liminal Spaces (2011), which documented the then-iconic landmark of Chennai – Hotel Dasaprakash – in its state of decay and imminent demolition. The series was a poignant meditation on the ephemerality of time, the nostalgia it evokes, and the impermanence of grandeur.

Another segment of the gallery, dedicated to her series “Wedding”, was adorned with makeshift archways bearing fluorescent-lit “Welcome” signs, reminiscent of the typical Tamil wedding decor. Inside, a collection of photographs captured sumptuously decorated wedding halls – opulent yet devoid of any human presence. The initial eeriness of this gradually gave way to a layered exploration of nostalgia, societal expectations, and the lavishness of wedding culture. Nandini Muthiah’s masterful use of colour and composition is deeply rooted in Tamil visual aesthetics, yet her true brilliance lies in transforming these elements into powerful storytelling devices – both profound and ingenious.

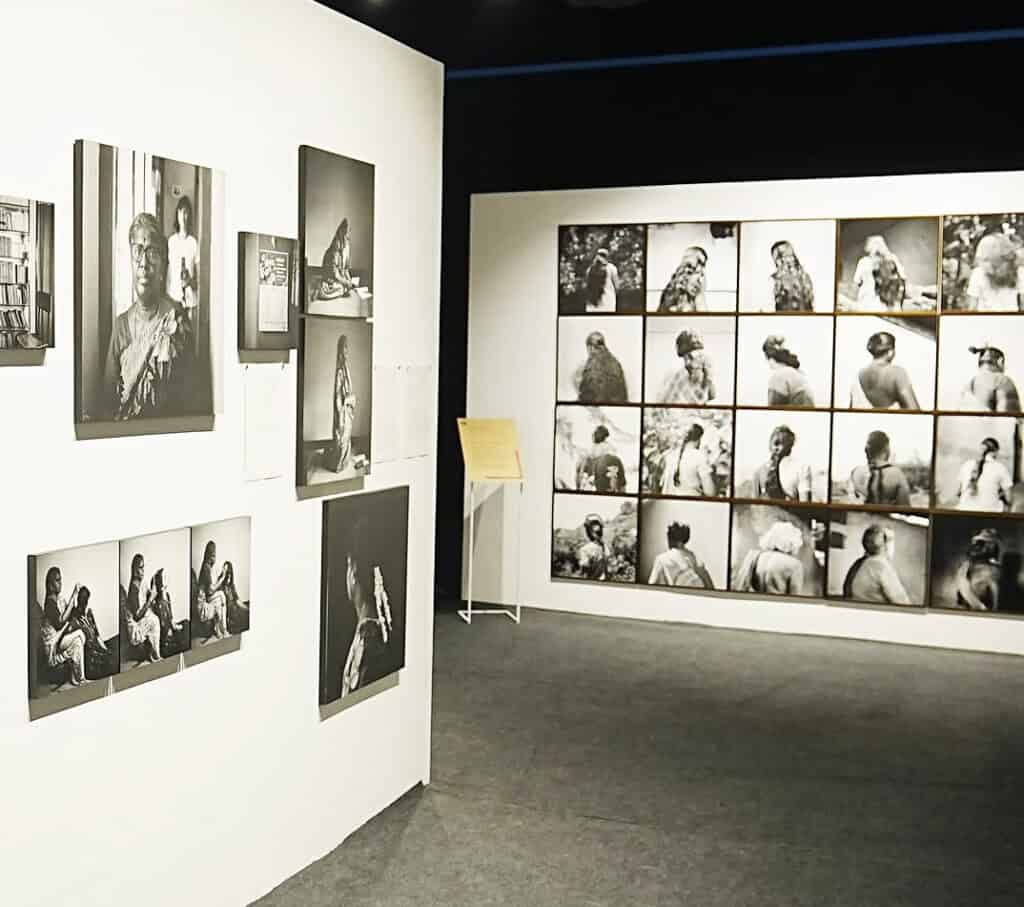

A portion of ‘Its Time. To See. To Be Seen.’

Upstairs, another compelling exhibition, It’s Time. To See. To Be Seen., featured photographs by female artists from around the world – spanning Kochi to Brooklyn to Gaza. Their works explored themes of freedom, identity, heritage, and the presence of women in public spaces etc., offering an essential reflection on contemporary society.

These exhibitions were part of the fourth edition of the Chennai Photo Biennale (CPB), which concluded on the 16th of March. Launched in 2018 in collaboration with the Goethe-Institut, this year’s edition was its most ambitious yet. What set CPB apart was its commitment to exhibiting visual lens-based arts in public spaces, ensuring unrestricted access to art. “Public art and art in public spaces have almost been the foundational principles of what we do at CPB,” says Gayatri Nair, Founding Trustee and curator at CPB.

Maasaru Katchiyavaruku (Those with Pure Vision), unseen archive of T. Lakshmikanthan. PC- artinidamagazine.

One of the most well-received exhibitions of the season was Maasaru Katchiyavaruku (Those with Pure Vision), featuring archival photographs by on-set photographer T. Lakshmikanthan. Unseen images from the sets of legendary Tamil films such as 16 Vayathinile and Alaigal Oivathillai, featuring the icons and beauties who defined Tamil cinema of the past, were displayed at the Tiruvanmiyur MRTS station- free for anyone to walk in and experience. Visitors spoke of how the exhibition transported them back to their youth, rekindling cherished memories of cinema’s golden age.

Liminal Spaces (2011), Nandini Valli Muthiah.

The Government Museum at Egmore housed two particularly compelling exhibitions. What Makes Me Click was a collection of photographs by children. It had over 200 photographs taken by children from across the world, offering a window into the beautiful and infinitely complex realm of their imagination, curiosity, and artistic experimentation.

Perhaps the most groundbreaking exhibition of the season was Love and Light, a retrospective of Sunil Gupta, India’s first openly gay photographer. Displayed at the Egmore Museum with the encouragement of Commissioner Kavita Ramu, IAS, the exhibition was publicly accessible and widely attended by individuals of all ages, genders, and sexualities. Its presence in a government museum was a landmark moment for queer representation in Indian art, making it an eloquent response to this edition’s overarching theme: Why Photography?

A remarkable feature of this edition was the architectural ingenuity embedded in many of the outdoor exhibitions, designed by The Architecture Story. Their approach went beyond aesthetics, becoming an intrinsic part of storytelling. Whether in Artists Through the Lens – a collection of photographs by Manisha Gera Baswani showcasing artists in their studios, displayed at the Raw Mango outlet – or the exhibitions at the Egmore Museum, the spatial design enriched the narrative.

One particularly evocative example was Love and Light, whose exhibition layout, when viewed from above, resembled an onion – a fitting metaphor for the many layers within Sunil Gupta’s work. This marks the third year of collaboration between The Architecture Story and CPB. “They are wonderful collaborators,” says Gayatri, “working closely with artists and curators, understanding the collections, and ensuring cost-sensitive execution.”

A portion of Vaanyerum Vizhuthugal shown at VR Chennai. PC – artindiamagazine.

The scale of public engagement this season was noteworthy. Vaanyerum Vizhuthugal, exhibited at VR Chennai, drew an astounding 90,000 visitors – a figure partly attributed to the mall’s role as one of the few third spaces in urban life, attracting millions of people each month. Relatability played a role too; the Tamil cinema exhibition at Tiruvanmiyur was inherently more accessible to a broader audience than the Baswani showcase at Raw Mango. However, CPB’s diverse curation extended an open invitation to audiences of all backgrounds. As Gayatri points out, a visitor drawn to the Tamil cinema exhibition or the children’s showcase might be encouraged to explore other exhibits, fostering a deeper engagement with themes that may be unfamiliar to them. Surveys reveal that 85 per cent of attendees were first-time visitors, with 7-8 per cent travelling from abroad – clear evidence of the event’s expanding reach and influence.

For centuries, Chennai has played a vital role in shaping Tamil Nadu’s artistic and cultural identity. However, contemporary visual arts have not received the same recognition as performing arts and cinema. This might explain why many Chennai-based artists choose to showcase their work in other prominent art cities like Mumbai or Delhi. Yet, collectives like CPB are changing this very narrative. With an open call for submissions, CPB provides a crucial platform for local artists, ensuring that Chennai’s vibrant and current artistic voices are heard. By fostering accessibility, innovation, and dialogue, CPB is not just enriching Chennai’s contemporary art scene – it is putting the city on the global map, one exhibition at a time.