(Continued from MM, XXXV, No. 9, August 16-31, 2025)

JP Rottler had availed help from Rev August Friedrich Cammerer, the last of THM missionaries, who arrived in Tranquebar in 1791. Cammerer had translated the first two parts of Tiru-k-kurał into German in 1803 and died in Tranquebar in 1837. William Taylor claims that himself and T. Vencatachala Moodeli (read as Thiruvannamalai Venkatachala Mudali) had invested an enormous effort in bringing the second part of this book out (Rottler’s Tamil-English dictionary). Taylor indicates,

‘… the revisions have been laborious. In addition to a great multiplicity of corrections, and some additions, complete portions have been written anew: all references have been verified; the Sanscrit ones corrected, in the orthography, to the uniform standard of Sir W(illiam) Jones’ system; and at least twice the former number of those references have been added.’

Part 3, published in 1839, includes 455 pages of text and one page of addendum. The title page indicates ‘W. Taylor’ and ‘T. Vencatachala Moodeli’ as the revising editors, immediately beneath ‘the late J.P. Rottler’. A short preface occurs at the beginning, which explains the delay in bringing out Part 3.

Part 4, published in 1841, includes 248 pages edited by Taylor and Venkatachala and this part includes a lengthy preface. Taylor clarifies that this preface offers contextual explanation for the entire four-part dictionary; this prefatory note had been delayed and could be included only in this part. Taylor speaks of the difficulties and disappointments experienced by him and Vencatachala, which however, have not been explained. He refers to the request made by James Francis Thomas (Madras Civil Service) and Daniel Corrie (Bishop of Madras, 1835-1837) to take up this task of editing and revising Rottler’s dictionary following Rottler’s sudden death.

Rottler’s service to Tamil lexicography

Linguistic interventions into Indian languages, such as Tamil, by foreign missionaries in India were an integral component of colonisation on the one hand and evangelisation on the other. Especially in the context of the latter, missionaries systematized their approach by defining a language grammatically and lexicographically. Such an approach implied the rendering of religious texts in local languages and in creating dictionaries (generically nikandu-s lexicons). One early example is the – Chatur-akarathi, a four-way lexicon – by the Jesuit Constanzo Giuseppe Beschi (1680–1747) in Madurai. Early lexicographic efforts enabled missionaries in gaining skills in and command over local languages by organizing words and by incorporating definitions, conjugations, and cataloguing their regional dialects.

One other key foreigner who studied Tamil language earnestly was Miron Winslow (1789–1864), who came to Madras from Virginia (USA) and who established the American Madras Mission along with John Scudder, Sr, in Chintadripet, in 1836. Winslow attained lexicographical standards in professing Tamil language, which fructified into print (Winslow 1862). Contributions by foreign missionaries later to the three – Fabricius, Rottler, Winslow – were not readily and always admitted, but can be recognized presently through meta-lexicographic study and the examination of the detail of their lexical selections and definitions (James 2017).

Rottler’s four-part dictionary impresses in the context of Tamil lexicography. The impressing strengths of Rottler’s Tamil-English dictionary are:

- The nouns and the third-person neuter singular of the verb are treated as headwords.

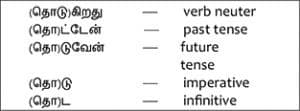

- The conjugated and imperative forms of verbs are supplied, following the third person neuter singular headwords.

- The conjugated forms of verbs are indicated after a ‘verb stem’, as preterite, future, imperative, and infinitive forms. Rottler was the first to indicate the grammatical structure of words in a dictionary. He also introduced the indication of transitive (verb active) and intransitive (verb neuter) forms in Tamil for the first time.

- The post position changes and related words are separately given following the headword.

- The grammatical structure of head words are provided.

- Sub-entries of a verb supplied with their meanings.

- Sanskrit-derived words were separately marked at the beginning of the word, referring to Horace Wilson (1819). Therefore, a reader could easily go through the references to extract more information on such words.

The treatment of third person neuter singular (intransitive verb) form from the dictionary, can be understood better from the example above (Box 1).

The treatment of third person neuter singular (intransitive verb) form from the dictionary, can be understood better from the example above (Box 1).

Rottler has not followed any order while providing the meanings of conjugated words. Reckoning with a language-learner’s need, he provides proverbs and literary examples, especially from Tirukkural. This practice of quoting relevant passages from literary texts is introduced by Rottler for the first time in Tamil lexicography, although they are between far and few. He has also included explanatory illustrations: e.g., for chakaram, he includes a line-sketch of a Yantra, an illustration sacred to the Hindus (vol.2, p. 204). Of course, illustrations render definitions and explanations in greater clarity, by supplying more details for given entries, yet concurrently tracking the historical growth of different shades of meanings and connotations of a word (University of Madras 1982, p. xliv).

In Rottler’s dictionary, grammatical notes that explain an ablative, adjective, adverb, imperative, infinitive, interjection, a masculine vs feminine, a negative vs positive, finite vs infinite participles, singular vs plural, prepositions, pronouns, substantive nouns, active, neuter, and intransitive verbs, and gerund usages are included. These grammatical explanations indeed paved the way for later-time Tamil grammars and lexicons. For example, that by Karl Graul (also spelt at Charles Graul), missionary of the Lutheran Leipzig Mission composed a Tamil grammar in 1855. Graul’s work largely followed the grammatical structures as defined by Rottler in his dictionary. Not all of the grammatical structures, explained by Rottler, are part of the traditional Tamil grammar. Dictionaries developed by missionaries, such as Rottler, are the only available handy texts for modern Tamil grammarians (Mathaiyan, 1997, p.10). Moreover, Tamil grammar texts, written later such as conjugation of verbs by Ragavaiyangar (1958) relied mostly on Graul’s text, that has followed the Rottler’s pattern and the later missionaries’ dictionaries (Mathaiyan, 1997, p. 10, 11).

Based on the descriptions given to headwords in this dictionary, Jeyadevan (1985) considers such descriptions are ‘exaggerated’ and hence the dictionaries are ‘highly inflated’. According to Jeyadevan,

– the descriptive explanation of words used in diverse dialects,

– those borrowed from neighbouring lands and languages,

– those used specifically by certain communities,

– those of slangy, brashy, colloquial use (Jeyadevan, 1985, p. 61),

are the features of this kind of dictionary. Jeyadevan thinks Rottler’s fulfil these features, hence fall under ‘highly inflated’.

Taylor explains that Rottler’s dictionary refers to all then recognized words, deriving them to either their roots or their primitives or their simplest forms, as closely as possible. Highly likely, the compilers, first Rottler and later Taylor and Vencatachala, intended this volume to help the natives and Europeans. Rottler’s dictionary, when published, was the most comprehensive compendium that included the best-word choices. Rottler’s dictionary remains a worthy monument to Tamil lexicography, particularly in its extensive tackles of derivatives (James, 2017, p. 176). However, Rottler’s dictionary includes exaggerated references to Astrology, Mythology, and Botany. Nonetheless, it proves an admirable effort, which is a refined production as against previous efforts, e.g., Beschi’s Catur-akarati, especially because Rottler attempted to show the syntactic function of words, including the conjugation patterns of verbs, and provided sentential exemplification of contextual use (James, 2017, p. 95).

Rottler must have acquired a clear sense of language by looking through and mastering the bilingual dictionaries published before his dictionary project. He had used the previously published dictionaries and the methods followed in them to enhance and enrich the quality of his work (University of Madras 1982). As an element of distinction from the preceding works, Rottler includes conjugations and compound forms of a stem word followed by the headword (various conjugations following each entry such as past, future, infinitive, imperative forms, which effectively enabled learners) that benefit a new language learner. This was especially helpful to foreign missionaries by serving them as a primer. For that reason, Myron Winslow (1862, p. vii) speaks highly as

‘…the dictionary of Dr. Rottler has been the only one professing to give any aid to the student in native books…; … great assistance has been derived from Dr. Rottler’s dictionary’.

Taylor’s commentary on Southern-Indian languages

In the preface in Part 4, Taylor speaks elaborately on the evolution of Tamil as a language. He refers to the un-relatedness between Tamil and Sanskrit, although he does recognize that many Sanskrit words were in use either as such or in a modified form in spoken and written Tamil. He contests the viewpoints of Henry Thomas Colebrooke (1805) and William Carey (1806). Taylor mounts his evidence in this contestation from the then recently published chapter the Note to the Introduction by Francis Whyte Ellis of the Madras Civil Service, in Alexander Duncan Campbell’s Grammar of the Teloogoo Language (1816). In the Note to Introduction, Ellis promulgated his revolutionary proposal on the independent origin of the Dravidian cluster of southern-Indian languages (Sreekumar 2009, Krishnamurti 2003). Building on Ellis’s argument (1816), Taylor speaks of the independent origin of Tamil language, quite strongly:

‘The Tamil language was only incidentally alluded to (sic. Sanskrit), chiefly by the latter; and some of the peculiarities of phrase introduced, although certainly conformable to the Tamil idiom, could just as well have been expressed much in the same way as the Sanscrit, and still have been idiomatic.’

Taylor further explains his point that he has taken care to clarify the stark distinctions between words that occur commonly in both Tamil and Sanskrit, the ‘comparative bareness’ of Tamil letters of alphabets, their innate inability to accommodate certain sibilant sounds that are unique to Sanskrit, achieved by the creation of new characters (Tamizh Grantham, 5th – 6th Centuries, see Ciotti and Franceschini 2016). Taylor maintains that the differences in pronouns, numerals, nouns, verbs, adverbs, and grammatical structures that are strongly distinct from comparable parts of speech and grammatical structures of Sanskrit reinforce his argument. One appealing comment by Taylor is the flexibility of Tamil, similar to English, evidenced in the written texts and spoken contexts of the 18th century English language champions Jonathan Swift and Samuel Johnson. Taylor explains this saying that both Swift and Johnson, although contemporaries, differed strongly in their writing styles. They employed utterly distinct languages, but both wrote with absolute clarity, precision, and used the rhetoric effectively and inimitably. Moreover, both Swift and Johnson applied satire in their spoken and written languages with sprightliness. Their tackles of the language and word selections reflect the evolution of language of their times. Taylor applies this contrast between two authors of the same period using the same language to the unrelatedness of Tamil and Sanskrit saying, ‘…it is possible to write a simple sentence in chaste Tamil and then to express the same meaning in words almost wholly of Sanskrit derivation: the difference, in the two instances, being something like the difference in the English styles of Swift and Johnson.’ From here, Taylor goes further comparing the evolution of Tamil with that of English over centuries. Taylor explains the adoption of foreign sounds (sibilants) and words incorporating sibilants into Tamil as ‘smoothening’ of the language. By smoothening, he means being ‘poetical’ and ‘mellifluous’. He speaks of utilizing the Catur-akarati by Viramamunivar (published edition dated 1824) to deal with some of the language complexities such as synonyms and for additional reasons pertaining to comparative aspects with the other Dravidian languages and Sanskrit.

Taylor concludes as follows:

‘No human work can be perfect; and perhaps no first impression of any large work ever issued from the press without being capable of corrections, or improvements, in subsequent editions. There has been no want of anxious care in this revision; and hence its magnitude, and difficulty, will, it is presumed, weigh in the comparison with any possible, and minor, errors. The perfect utility of such a work consists in perfect accuracy. Perfection has been aimed at; but it would be presumption to state that it has been attained.’

Conclusion

We — the authors of the present article — are happy that we have succeeded in bringing a ‘portrait’ of Rottler (vide the monumental tablet sculpted by Richard Westmacott, Junior) to light. Born in Alsace, Rottler chose to start missionary work and came to Tarangampadi (c. 6000 km from Copenhagen, where he was ordained) crossing the seas. He mastered both Tamil and English in the shortest time possible. He enthusiastically maintained his botanical interest for more than three decades, simultaneously devoting to evangelization. Importantly he developed the Tamil–English dictionary for which he completed the preliminary work for all of the four parts. Unfortunately, he died midway while working on part 2. The publication of parts 2 to 4 was completed jointly by William Taylor, an independent protestant cleric of Madras and Vencatachala Moodeli, a Tamil teacher attached to the College of Fort St George, College Road, Nungambakkam, Madras. Taylor’s preface in Part 4 provides a detailed longitudinal perspective of the history and development of the Tamil language over time and also the specific measures he and Vencatachala administered when they were working in this project. We conclude that Rottler’s dictionary evolved in the period of transition of the Tamil lexicography.

Acknowledgement

We are grateful to Professor PS Ramanujam, Danmarks Tekniske Universitet, Kongens Lyngby, Denmark, for reading and commenting on the pre-final draft. One of us — MVP — visited the CSI St. Matthias Church, Vepery and saw the Westmacott sculpture of Rottler on display. MVP gratefully acknowledges the help and enthusiasm of the administrators of CSI St Matthias Church and Mr Enos.

— Muthu V. Prakash, Anantanarayanan Raman

(Concluded)