Johann Peter Rottler arrived in Tarangampadi (Tranquebar) near Karaikkal on India’s Coromandel Coast to serve as a cleric for the Tranquebar-Halle Mission in 1776. Trained as a botanist, he pursued botany passionately, while in the Coromandel. In the second decade of the 19th century, Rottler started compiling a Tamil-English dictionary. His four-part dictionary is profound in the annals of Tamil lexicography. His notes on Tamil grammar in that dictionary explain the ablative, adjective, adverb, imperative, infinitive, interjection, a masculine and feminine, negative and positive, finite and infinite participles, singular and plural, prepositions, pronouns, substantive nouns, active, neuter, and intransitive verbs, and gerund usages. These impress when viewed against the then extant lexicons published in the 18th century by Beschi, Fabricius and Breithaupt. Grammatical explanations available in Rottler’s dictionary have influenced later grammatical reforms made in Tamil language and literature. Taylor, who completed the remaining volumes of the dictionary after Rottler’s demise, his multi-page notes in part 4 provide a sharp — albeit contentious — comment on the uniqueness of the Tamil language, pitched on the concept of independent origin of Tamil by Francis Whyte Ellis of Madras Civil Service proposed in early 19th century. In our present article, we have managed to bring Rottler’s portrait to light, so far not known, from a sculpture by Richard Westmacott of Britain. Our explanation, commentaries, and evidences included in this article validate that Rottler’s Tamil-English Dictionary came about in the period of transition of Tamil lexicography and has shed critical light on Tamil language.

Keywords: Rottler, Lutheran, Tamil, Dictionary, Missionary, Taylor, Vencatachala Mudali.

* * *

‘Among the most essential benefits he (JP Rottler) conferred on the mission (Vepery Mission) in his private hours, were a revision of Fabricius’s Translation of the Old Testament, and the preparation of a Tamil version of the Liturgy of the Church of England…(and) engaged to the last days of his valuable life in compiling a Tamil and English dictionary…to which he had devoted a certain portion of his time for twenty years.’

– The Saturday Magazine (No. 389, July 28, 1838, p. 26)

* * *

Figure 1. Cover page of JP Rottler’s A Dictionary of the Tamil and English Languages (1834).

The above, published two years after Rottler’s death in Madras (now Chennai), grandiloquently refers to the effort invested by Rottler in compiling a Tamil-English dictionary, which is, a unique effort for various reasons. As a Protestant missionary, Rottler – earlier committed to evangelizing in Tarangambadi in slightly southern coastal Tamil country earlier and in Madras city later – evinced keen interest in knowing and collecting scientific information about the plants of the landscape he lived in and travelled around. He mastered the Tamil language so much that he could compile the Dictionary of Tamil and English Languages in 1834 (Fig. 1). Chronologically, this dictionary follows the Malabar and English Dictionary (1779) by Johann Philipp Fabricius from Frankfurt (a free imperial city within the Holy-Roman Empire) co-written with Johann Christian Breithaupt from Dransfeld (near Göttingen, then under the Kurfürstentum Braunschweig-Lüneburg within the Holy-Roman Empire). However, Rottler’s dictionary is the first of the kind that includes grammatical categories of headwords and offers defined directions to present-day Tamil grammar, differing from the dictionary compiled by Fabricius and Breithaupt. The present article considers Rottler’s effort in compiling the Dictionary of Tamil and English Languages, in addition to providing a short narrative of his life in India.

Rottler’s life and service to Protestantism

A narrow ‘Rotler Street’ (spelt with one ‘t’) connects Hunter’s Road in Vepery and Avadhanam Pappier Road in Perambur in the present-day Chennai. This street commemorates J(ohann) P(eter) Rottler, who lived in this area for nearly three decades in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, while attached to the Vepery Mission, which functioned under SPCK (Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge) of London, established in 1728.

Rottler arrived in Tranquebar to serve as a cleric of the Halle Mission (The Tranquebar Halle Mission [THM], Royal Danish-Lutheran Mission, and Tranquebar Mission) in 1776. Work of the THM formally commenced with the arrival of Bartholomäus Ziegenbalg and Heinrich Plütschau in Tranquebar, deputed by Fredrick IV, the king of Denmark, in 1706. Ziegenbalg and Plütschau were the pioneers of the Lutheran-Church Mission in India. Incidentally the effort of THM missionaries also promoted the start of western-style schools and a printing press shortly after, which popularized the Lutheran Mission in southern India (Sherring and Storrow 1884).

Rottler was born in Strasbourg, Alsace (then in the Kingdom of France; presently in the Region Grand Est, north-eastern France) in 1749. Rottler completed high school at the Strasbourg Gymnasium and higher studies (Botany?) at the University of Strasbourg by 1766-1775. Johann Anastasius Freylinghausen of the Franckeschen Stiftungen, Halle (Freistaat Sachsen, Deutsche Bundesländer) selected Rottler and Johann Wilhelm Gerlach of Frankfurt to work as clerics for the THM. Rottler and Gerlach were ordained as priests in Kobenhavn (Denmark) by Ludvig Harboe, the Bishop of Sjælland (Capital Region of Denmark) in 1775. When Rottler and Gerlach arrived in Tranquebar, the THM was directed by Johann Caspar Kohlhoff. Other well-known names of the THM at that time were Johan Gottfried Klein and Christoph Samuel John. Gerlach moved to Calcutta in 1778 and Rottler remained in Tranquebar. One other familiar name of the THM at that time was Christian Friedrich Schwartz, a close associate of Sarabhendra Bhupala Bhupati Bhosle (Serfoji II, 1777-1832), the Mahratta ruler of Tanjavur (Nair 2012). Rottler died while at the Vepery Mission in Madras city in January 1836 and is interred in the Vepery-Mission precinct, today the yard of St. Matthias’s Church (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Rottler (right) explaining the New Testament to an Indian (left) in Tamil (monumental tablet, cut by Richard Westmacott Jr). Source: The Saturday Magazine (published by the Committee of General Literature and Education, sponsored by the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, London), Issue 389, 28 July 1838.

Rottler made great efforts to master Tamil language from the time he arrived in Tranquebar (Mohanavelu 1993). He could deliver a Tamil sermon within a year of arrival, although his name does not figure prominently in THM records during first few years of his stay in Tranquebar. He accompanied his seniors on several local-missionary trips. In his diaries, he has recorded plants in the locations he had gone to. By 1779 he was reasonably advanced with his English-language skill as well. A minor detail would be that he was married to a Dutch lady (name unknown) in Cochin in 1779; they did not have any children.

Interest in southern-Indian plants

Rottler was awarded an honorary doctorate (indicated variously: as ‘P.D.’, ‘D.Ph.’, for Doktor der Philosophie) by the University of Erlangen, Bavaria (currently die Friedrich-Alexander-Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg, Bayern) in 1795. Whether this award was in recognition of his botanical or medico-botanical or evangelical work is unclear. Rottler enthusiastically pursued the botany of the Coromandel. He gathered information on the medicinal relevance of local plants from people around and the indigenous doctors. He avidly collected plants and maintained most of them living in the botanical garden attached to the THM. Because Tranquebar flourished with an intellectual community of missionaries and non-mission Europeans, the Tranquebarian Society (TS) with an aim to promote science, enlightenment, and useful knowledge, was established in 1788. As a part of the scholarly pursuit of the TS, proposals for establishing a library, a natural-history repository, and a botanical garden were considered (Jensen 2005, Raman 2017). Christoph John, a senior colleague of Rottler, argued in favour of a botanical garden. The TS approved John’s proposal and it managed to acquire c. 30 ha of barren land, a little north of Tranquebar, from the administrators of the Danske Ostindiske Kompagni. Rottler became the keeper because of his botanical avidity (Ramanujam 2021). William Roxburgh, a renowned name in Indian botany (Robinson 2008) and Rottler were in close contact, discussing plants of southern India. Rottler’s botanical diaries, notes, and occasional formal reports were considered valuable by eminent botanists of the day. For example, many of Rottler’s observations are credibly cited by the Scottish botanists Robert Wight and George Arnott Walker-Arnott in their Prodromus Florae Peninsulae Indiae Orientalis (1834) and the English botanist Joseph Dalton Hooker and surgeon-botanist Thomas Thomson in their Flora Indica (1855).

On a road trip from Tranquebar to Madras and back, in the late 18th century, Rottler collected plants en route. Details of this collection are available in Botanische Bemerkungen auf der Hin-und Rückreise von Trankenbarnach Madras vom Herrn Missionair Rottler zu Trankenbarmitanmerkungen von Professor CL Willdenow (the Botanical remarks on the onward journey from Tranquebar to Madras and return to Tranquebar by Mr Missionary Rottler with notes by Professor CL Willdenow) published in the Gesellschaft Naturforschender Freunde zu Berlin [Neue Schriften] (Berlin Society for Naturalists, New Series) in 1803. Carl Ludwig Willdenow (1765-1812, Professor of Botany, University of Berlin), the author of this article refers to plants collected by Rottler along the Coromandel in 1799-1800.

Willdenow provides detailed notes in German and descriptions of some plants in Latin under three headings: (i) during travel from Tranquebar to Madras (24 September-7 October 1799), (ii) in Madras and its neighbourhood (8 October-28 December 1799), and (iii) during return to Tranquebar via Wandiwasi (Vandavasi) near Cudelur (Cuddalore) (28 December 1799-16 January 1800) (Stansfield 1957). A detailed commentary on this Willdenow article is available (Raman and Prasad 2010).

Rottler accompanied Frederick North (1766-1827), the first British civil Governor of Ceylon (now ‘Sri Lanka’) (1798-1805) responding to Frederick North’s request to accompany him during his exploration of Ceylon. Rottler collected plant specimens from there and donated the herbarium sheets of Ceylon plants to King’s College, London, on return. Karl Wilhelm Päzold (spelt variously: ‘Paezold’, ‘Paetzold’, ‘Pezold’, ‘Pezoldt’) returned to Vepery from the College of Fort William, Calcutta, where he was teaching Tamil language. Shortly after, Päzold died in Madras. Consequently Rottler was absorbed into SPCK Mission service, filling the vacancy created by Päzold’s sudden death.

Due to various developments, in 1807, Rottler had to step down from his role in the Vepery Mission and return to Tranquebar. Subsequently he disconnected himself from THM and a little later from the SPCK as well. At this time, William Bentinck (William Henry Cavendish Bentinck), Governor of Madras (1803-1807) and Governor-General of India (1834-1835) appointed Rottler as the Chaplain–Secretary of the Madras Female-Orphan Asylum on Poonamallee High Road in Aminjikarai which transformed as the St. George’s School and Orphanage from 1954; presently the St. George’s Anglo-Indian Higher Secondary School), Chennai. Rottler was restored to his earlier position at the THM by Peter Anker (Governor, de Danske Kolonier, Tranquebar, 1786-1808). However, because Tranquebar soon came under British control during the administration of Richard Wellesley (Governor-General of India, 1817) the dynamics changed. At this time of separation from the THM, Rottler commenced compiling the Tamil-English dictionary, while at the Vepery Mission. Rottler translated a few German and one English prayer books into Tamil. On his contributions, Thomas Foulkes of the Church Missionary Society, first in Tirunelveli and later in Madras, and an Indologist of distinction, writes (1861, p. 11):,

‘… necessarily accompanying so extensive a work, has been of infinite service, and continuing still unsuperseded as the standard Tamil dictionary’.

Rottler’s Tamil–English dictionary

Rottler’s Dictionary of Tamil and English Languages consists of four parts. The first part was printed and published by Rottler in 1834. The subsequent parts, viz., 2, 3, and 4, were printed and published in 1836-1841 under the supervision and editorial direction of William Taylor and T. Vencatachala Moodeli (read as Thiruvannamalai Venkatachala Mudali).

William Taylor (1800?-1879) came to Madras to join the Madras Army maintained by the English East India Company. Shortly after, Taylor quit army service and got himself ordained as a Protestant clergy affiliated with the Vepery Mission in 1839. He quit the Vepery Mission shortly as well, preferring to remain as an independent clergyman in Vallaveram (= Villupuram, Penny 1904). In later years, he lived in Madras city in retirement in Coleman’s Garden (c. 1-acre garden house on Lawder’s Gate Road, Purasawalkam village, Tondiarpet Taluk, Madras [= Chennai] (details as in the registered Sale Deed of 27 February 1920, Document # 365 of 1920, Sub-Registrar Office, West Madras; Real-Estate Regulatory Authority, Government of Tamil Nadu, https://rera.tn.gov.in/ public/storage/ upload/pdf, accessed 5 June 2025). In 1834, Taylor examined the Colin Mackenzie manuscripts and Taylor’s commentaries on them are available in the early issues of the Madras Journal of Literature and Science. The maximum information we could gather on Vencatachala Moodeli was that his name was Tiruvannamalai Venkatachala Mudaliar, a certified-Tamil teacher, attached to the College of Fort St. George on College Road, Nungambakkam (Srinivasachari, 1927).

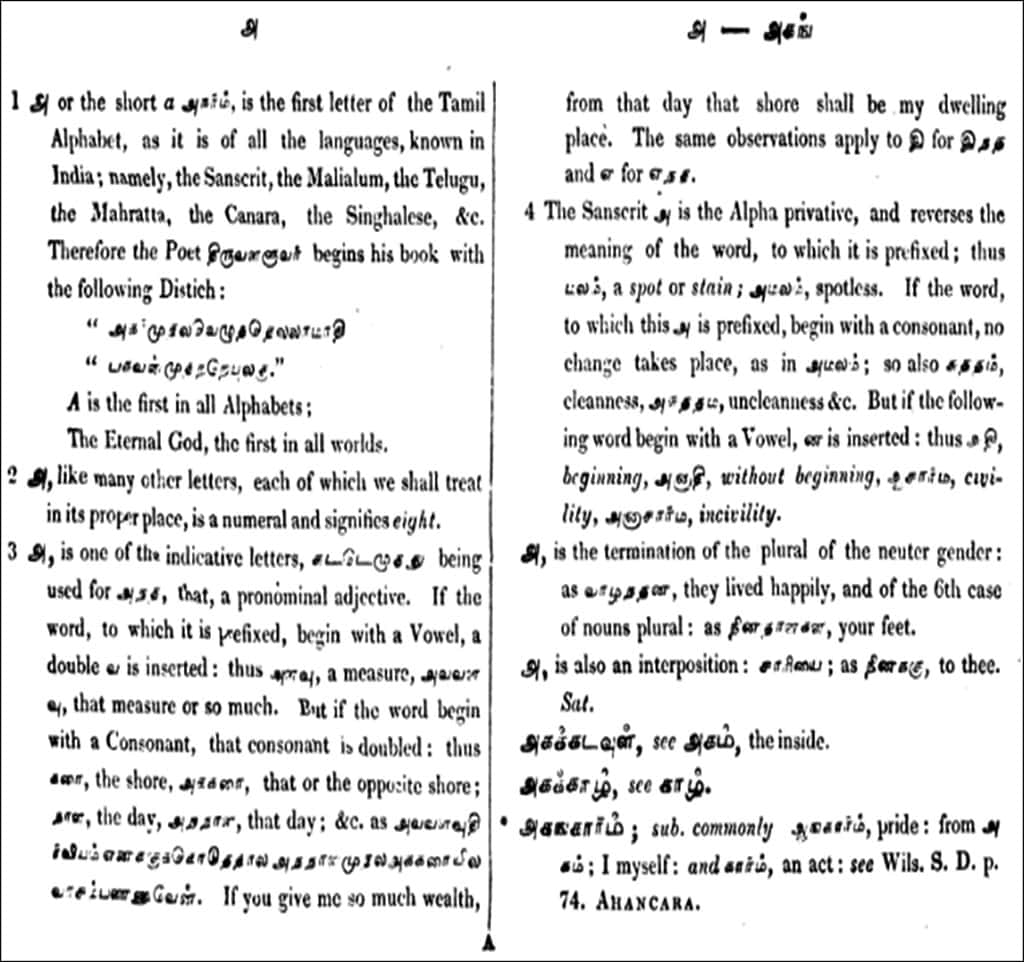

Figure 3. A sample page from Rottler’s A Dictionary of Tamil and English Languages, Part 1 (1834).

Part 1 of Rottler’s Tamil-English dictionary (Fig. 3) consists of 298 pages of text and two unnumbered pages of ‘Additions and Corrections’, ‘Explanation of Abbreviations’. This part was published after Rottler edited and proof-read it himself. A dedicatory note addressed to William Bentinck (Governor of Madras, 1803-1807), dated 24 March 1834, occurs in this part. Rottler uses a pompous English prose here. Other than this, nothing as a preface explaining the intent and context of this work exists. The dictionary text is elaborate and includes supplementary comments relating to comparative linguistics as pertinent to other Dravidian languages and Sanskrit.

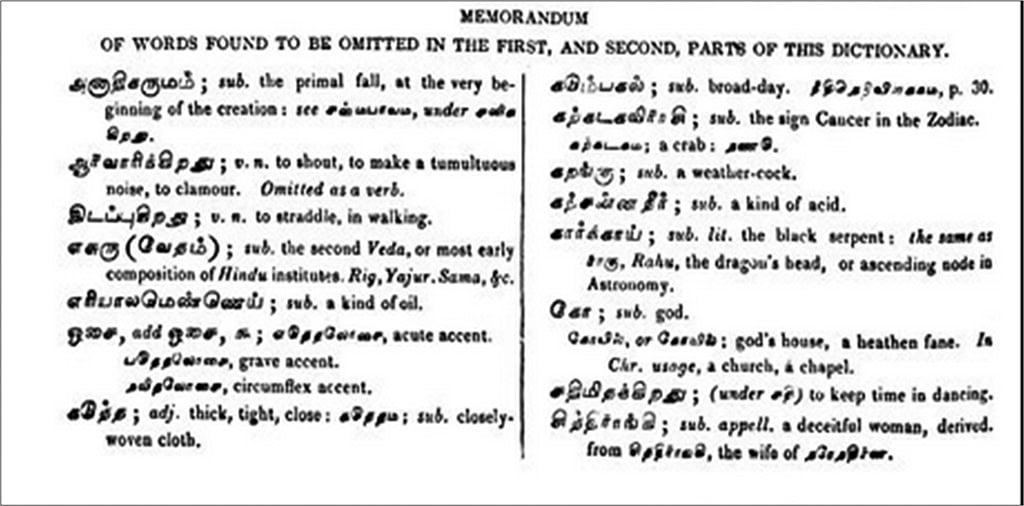

Part 2 was published in 1836-1837. The title page indicates Rottler as ‘the late JP Rottler’, since Rottler had died on 24 January 1836. Obviously, this part was proof-read and brought out by Taylor and a college ‘moonshee’ (Vencatachala). The second part consists of 410 pages of text and 10 pages of errata. The bottom half of the page numbered Roman numeral ‘x’ includes a list of words omitted in parts 1 and 2 (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Omitted words in parts 1 and 2 (page x).

A short preface — by Taylor — indicates that Rottler had edited and finalized the text up to page 204 (as in the print edition). Taylor clarifies that to carry out the task up to this point, Rottler had availed help from Reverend August Friedrich Cammerer, the last of THM missionaries, who arrived in Tranquebar in 1791.

— by Ramya Raman, Anantanarayanan Raman

(To be concluded next fortnight)