|

The English language acquired its foothold in India in distinctly different ways in two of British India’s Presidencies, Madras and Calcutta. An examination of the historiographic record on the development of the English language in India suggests that it was a colonialist imposition. This was largely true of the Calcutta experience that historians have chosen to focus on. However, in the Madras Presidency – generally overlooked by historians – the growth of the language benefited from the collaborative efforts of many players, both native and British. Far from being viewed as an imposition, the natives of Madras both demanded and supported the implementation of an English language policy.

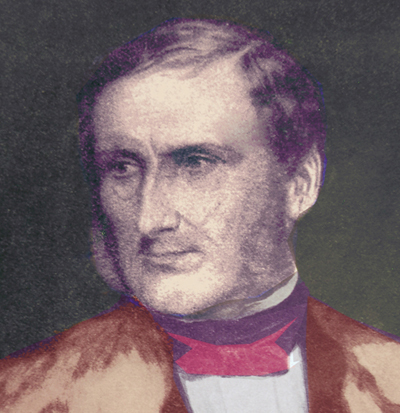

Lord Elphinstone |

It was not until the arrival of Sir Thomas Munro as Governor of Madras in 1820 that concrete steps were taken toward the formation of an education policy for Madras. While Munro’s efforts at administrative reform are well known, his contribution to education has largely been ignored. Munro realised that the insular British administration, with its racial prejudices and language limitations, hindered effective governance. Lack of sufficient British personnel also meant that Government had to extensively rely on the languages skills of dubashes and other natives, some of whom indulged in embezzlements and fraud.

The solution to these problems lay in educating the native population. Little was known about the state of education in the Presidency before Munro’s time. Munro realised that if Government was to play a role in the sphere of education, it was important to first understand the state of education in the Presidency. “We have made geographical and agricultural surveys of our provinces; we have investigated their resources, and endeavoured to ascertain their population; but little or nothing has been done to learn the state of education,” Munro stated.

In 1822, Munro ordered a comprehensive survey on the state of education of the people of Madras, with each District Collector engaging in a detailed study that documented the complete list of schools in each district along with the number of scholars and teachers, caste and gender to which they belonged. The survey, which was completed in 1825, provides a detailed and fascinating view of education during the time. 188,650 students attended 12,498 schools out of a total population of 12,850,941 in the Presidency – only one school per 1000 persons and one student per 67 persons.

Munro then came up with the first set of Government proposals to improve the state of education. All schools in the Presidency were to be supported by an endowment from the Government. This was a radical proposal at the time. From being a non-participant, Munro was now proposing that Government become a sponsor of all education. What is truly remarkable was that Munro was fully cognisant of and sympathetic to native fears about British interference in their schools. He wrote, “It is not my intention to recommend any interference whatever in the native schools. Everything of this kind ought to be carefully avoided, and the people should be left to manage their schools in their own way.”

Munro set the tone not only for his adminsitration’s policies, but that of successive governments as well. In the decades to follow, the Madras Government’s educational policy would be collaborative rather than confrontational. The Court of Directors of the East India Company (Indian rule had not passed on to Parliament yet) warmly applauded Munro’s approach. Unfortunately for Madras, Munro died in July 1827.

Munro’s successors Stephen Rumbold Lushington and Sir Frederick Adam did little to build on the foundation laid by Munro. However, the one bright note in Madras education was the dubash Pachaiyappa‘s bequest, which was used for the purpose of English language education at the suggestion of the then Advocate General, George Norton.

By the turn of the 19th Century, the city of Madras was well on its way to becoming one of India’s largest and most prosperous cities. With a population in excess of 250,000, the erstwhile fishing village was rapidly transforming itself into a bustling centre of government, commerce and culture. Rising economic activity gave birth to supporting institutions such as banks and insurance companies. By 1812, there were twelve agency houses in Madras with such well-known names as Arbuthnot, De Monte & Co., and Parry & Pugh. The flourishing trade also attracted Portuguese, Jewish and Armenian merchants, giving the city a distinct cosmopolitan feel.

Coincident with, and contributing to the rise of Madras, was an upwardly mobile Indian mercantile class. This mercantile elite migrated from the deep Tamil-speaking south as well as from the Telugu-speaking country. The new Hindu gentry with its growing economic and social power sought English language education. They realised that knowledge of English enhanced their reputation with the British, paved the way for easier trade dealings with Europe, opened the doors to plum Government positions, and gave them the ability to negotiate directly with the British on their own terms, all of which formed the basis for a new self-confidence and ability.

Encouraged by George Norton, the leaders of the Hindu community formed the Hindu Literary Society in 1830. One of the leaders of the Society was Gajalu Lakshmanarasu Chetty, born into a komati merchant family in Madras in 1806. On completing his elementary school education in a local school, where he developed a fair proficiency in English, he joined his father’s agency firm,

G. Sidhulu & Co. Skilful speculation in the textile and indigo trades helped Lakshmanarasu Chetty’s family grow into one of the wealthiest in Madras. Another leading member of the Hindu Literary Society was C. Srinivasa Pillay. The scion of a rich, upper caste Hindu family, Pillay believed that Western education was the key to India’s regeneration. A trustee of the Pachaiyappa trust, the socially-minded Pillay was a close friend of George Norton and came under the influence of his progressive views.

Meanwhile, missionaries exploited the vacuum left in education by Munro’s death. Alexander Duff was one such missionary. Duff arrived in Calcutta in 1830. Duff’s brand of fiery and intrusive missionary zeal had its origins in the Scottish Enlightenment. Duff organised a school that taught history, geography, arithmetic, and Christianity. Sticking to the principle of downward filtration, Duff felt that converts (to Christianity) from ‘respectable families’ would be the torchbearers in a new line of self-perpetuating congregations in India. His associate missionary, John Anderson, who opened the Scottish Free Church School in Black Town, Madras, in 1837 carried on Duff’s work in Madras. The purpose of the school was to impart a distinctively European type of education, with a focus on Christianity, communicated through the English language. Despite the clearly stated Christian mission of the school, it appealed to the deeply felt need for English language education among the growing Hindu elite of Madras. The school was so popular that it outgrew its premises three times within the first decade (the school later became Madras Christian College).

The leaders of the Hindu Literary Society were alarmed by the growing missionary influence in Madras. They realised that the desire for English language education among the elite Hindu was so great that Hindu families were prepared to take the chance of sending their children to missionary schools despite the risk of religious conversion. To Lakshmanarasu Chetty, Srinivasa Pillay, and Narayanaswamy Naidu, another leader of the Hindu Literary Society, fell the task of responding to the emerging missionary threat.

It was the arrival of John Elphinstone as Governor of Madras in 1839 that resulted in an extraordinary partnership between the Hindu elite and the British establishment in the sphere of education. Like Munro, Elphinstone evinced a keen interest in education and believed that Western education was the right tool to regenerate the natives of Madras. He wrote, “Nothing is more honourable to our rule than the attention paid to the subject of education of the people.” Anxious to make education a central theme of his administration, he laboured to gain a mastery over the state of affairs of education by studying official papers and consulting both officials and non-officials in Madras. He had a knowledgeable ally and assistant in his Advocate General, George Norton.

The Hindu Literary Society led by Chetty, Pillay and Naidu quickly realised that the only way to counter the growing missionary threat was for a secular-minded Government to enter the business of English language education. In Lord Elphinstone they found an ally who was not only secular but had an interest in education. Towards that end, they gathered over 70,000 signatures and submitted a petition to Lord Elphinstone on November 11, 1839 (the original petition is now housed in the Asia Pacific and Africa Collections of the British Library in London). The petition, written in English, Tamil and Telugu, with signatures in Tamil, Telugu, English and Devanagari appealed to Elphinstone “for the establishment of an improved system of national education in the Presidency.” While its sister Presidencies had collegiate institutions (Hindu College in Calcutta and Elphinstone College in Bombay), Madras had none. But the petitioners made clear that religious neutrality in education was a priority. “Any scheme for National Education interfering with the religious faith or sentiment of the people may prove abortive,” they warned. Finally the petitioners urged for a share in the educational measures that Elphinstone was contemplating.

The magnitude and importance of the petition were not lost on Elphinstone. In a letter to Norton in 1840, he wrote that the address “which was last year presented to me on the subject (of education), more numerously signed than I believe any similar document ever was in India,” was proof that this was not a document to be taken lightly. Moreover the petitioners’ demand was consistent with his goals for education – Western education and learning, non-interference with their religion, and a share in the formation and implementation of educational policy.

Elphinstone responded with his Minute on Education dated December 12, 1839, exactly 31 days after receiving the petition. In it he outlined his plan for education in the Presidency, the centrepiece of which was to be the establishment of a collegiate institution in Madras city, intended to “stand in the same relative position” to the colleges in Scotland and England. In affirming his Government’s support to religious neutrality in education, Elphinstone stated that care should be taken to “avoid whatever may tend to violate or offend the religious feelings of any class” and no part of the design of the institution would “inculcate doctrines of religious faith, or supply books with any view.” In acceding to the Indian request for a share in education, Elphinstone recommended that the University have fourteen Governors, “seven of whom shall be Native Hindoos or Musselmen.”

As a result of Elphinstone’s recommendations, the Madras University Board was formed in May 1840 with George Norton as its President and Srinivasa Pillay as a nominated member. On the morning of Wednesday, April 14, 1841, the Madras University was formally inaugurated at the College Hall in Madras. Besides his Lordship the Governor, the occasion was graced by the Nawab of the Carnatic, members of the Governor’s Council, the President and Governors of the University Board, and a large number of influential Madras residents.

Elphinstone returned to England in 1842. Lakshmanarasu Chetty continued to support Hindu causes by buying the Crescent, a pro-Hindu newspaper, to counter the missionary threat of another daily, the Native Herald. The Crescent, placed under the editorship of Edward Varley, a school teacher in Vepery, emerged as an outspoken advocate of Hindu causes. In 1852, the Hindu Literary Society morphed into a political organisation called the Madras Native Association under the leadership of two leading Madras natives of the time, C. Yagambaram Mudaliar and Ramanuja Chari. Srinivasa Pillay went on to form the Hindu Progressive Improvement Society, which championed the cause of female education and widow remarriage.

Unlike the experience of Calcutta, where English was viewed as a colonialist imposition under the rabid Angliscist influence of Thomas Macaulay, Charles Trevelayan and Lord Bentinck, the Madras Government had charted its own consultative, collaborative path under the leadership of Munro, Elphinstone, Norton and other leading administrators, that enabled a smoother and more productive introduction of the English language in partnership with leading Madras intellectuals.

Their English was spell-binding

Coming across the name of V.S. Srinivasa Sastri in a recent issue of Madras Musings, I was reminded of the distinguished scholar who rose from being the Headmaster of the Hindu High School in Triplicane to being a Privy Councillor in London during the Raj. It was a coveted honour and entitled him to be called the Right Hon’ble (Srinivasa Sastri). The honour was a significant result of his cultivation of his knowledge of English and its accent. The Concise Oxford Dictionary was said to have been his constant companion and helped him to perfect his pronunciation. I have heard him speak in the Kellet High School in Triplicane, lecturing on the Ramayana. It was a constant flow of mellifluous words which expounded the epic of old in lucid terms. Sastri was heard with rapt attention because of his English as much as for the content. No wonder he was hailed as the “silver-tongued orator.”

He was, in fact, one of a long line of public speakers in English who were the toast of the 1940s and ’50s in Madras. Sir C.P. Ramaswami Aiyar was a towering personality in public speaking of those times. Impeccably dressed, he once gave a lecture, which was equally impeccably constructed, in the Ranade Hall in Mylapore. It was to the point and lucid, and whatever he said was mulled over later by his audience to get the full impact of his ideas.

Dr. C.R. Reddy, educationist and scholar, had his own way of presenting his points. His lectures on ‘Indian Democracy’ in a hall on the first floor of Senate House had overflowing audiences because of the intellectual veneer of his thought and speech. His speeches had no frills, but the very force of the ideas he presented would overwhelm the audience.

Speaking of Senate House, I cannot but recall Dr. A. Lakshmanaswami Mudaliar, the record-setting Vice-Chancellor. He was a forceful speaker but with a slightly sing-song manner of speaking which did not detract from the flow of ideas and the lucidity of his language. His twin brother, Sir A. Ramaswami Mudaliar, was different from his younger brother. With his rich voice, whatever he said – and what he said was always well thought out – went down well with audiences.

On the Kashmir question, V.K. Krishna Menon’s speech in the U.N. was a record performance. Quaffing cups of tea, as was his wont, he spoke sharply and with rapier-like wit. Soon after, when he came to Madras, he was invited to Presidency College to speak in the Big English Lecture Hall. He held forth, sharp and attorney-like.

A speaker of a different type was Sir C.V. Raman. It was again in the Big English Lecture Hall which has a very big stage. Dr. Raman spoke on crystals, and it was evident that his whole being was suffused with science as he moved this way and that on the stage, presenting enthusiastically and in simple, clear terms whatever needed to be understood of the facts of crystal science. It was a popular science lecture of unsurpassed value from a great scientist.

The same venue was host to Dr. Pattabhi Sitaramayya, a doctor who joined the Indian National Congress and made it to the highest level as a candidate for the presidentship of the party backed by the Mahatma himself against Netaji. Later, he wrote a history of the Congress, a valuable contribution from a veteran about the growth of the party. He was a great spokesman of the party and presented its viewpoint straightforwardly and unemotionally.

For sheer individuality and a distinctiveness of regional flavour, Justice A.S.P. Aiyar should be recalled. He had a witty approach and loaded the lecture with witticisms which sent the audience into peals of laughter. Yet there was an intellectual base to his humorous comments on men and affairs; you came away from his lectures laughing, but also moved to think about what he had said.

P.V. Rajamannar, who was Chief Justice of the Madras High Court, was on the side a literary figure, playwright and theatre enthusiast, and an art connoisseur. I remember even now how, when speaking at the inauguration of an art event in Mylapore, he made a long, lyrical statement that got spontaneous applause.

These are a few of the speakers in English who made the intellectual scene in Madras lively in the early days of Independence.

– M. Harinarayana

120/154 Big Street

Triplicane, Chennai 600 005

|

|