It was November 1960. I had just returned from my annual leave spent in Madurai to join the ship I was sailing in – an apology of a ship as it was an old mine sweeper of WWII vintage that was transferred to the Indian Navy after Independence. Just about 110 ft long, it rolled and pitched so much that even a hard-core sailor would feel miserable while sailing. A few days later after joining the ship, I received a signal (usually messages are referred to as signals in the Navy) asking me to report to Mumbai HQ as I was selected to man the first Indian Aircraft carrier, launched as HMS Hercules and rechristened as INS Vikrant. Incidentally, HMS Hercules, a Majestic-class light fleet aircraft carrier, was launched in 1945 but never completed by the Royal Navy. Taken over by the Indian Navy, the construction was completed in the Harland & Wolff shipyard in Belfast, North Ireland. It was commissioned as INS Vikrant in 1961 and served the Indian Navy until 1997. I was deputed to the Harland & Wolff shipyard in Belfast, as part of ship procurement crew to standby during its construction.

There was, as usual some delay for certain clearances and I had to wait for a while. It was then that two super-speed fast boats (named Sarada and Sukanya) fitted with 36-cylinder Mercedes engines imported from Germany, to safeguard the Gulf of Mannar against insurgents and illegal transportation, arrived at Madras harbour. They were to be taken charge of, and I was asked to proceed to the then Madras for that purpose and was given accommodation at INS Adyar which was housed inside the fort, with a foul-mouthed Punjabi, Commander Sonpar as its head. I took an instant dislike to this man. He had an old Chevrolet car and that needed some repairs. Cdr Sonpar asked me if I could set that right as I was trained as an artificer in INS Shivaji. I told him that there are dime a dozen motor mechanics in the city who could be asked and not a marine engineer like me. That put him on the boil, and he informed the headquarters that I was a bad influence on the ship’s company and should be immediately drafted elsewhere. Since I was already drafted to join Vikrant, I was sent to INS Circars in Visakhapatnam to wait for a call to proceed to the UK.

When the call came, I wanted to teach a lesson to Cdr. Sonpar and so I asked the drafting centre in Bombay to send me to INS Adyar where I had my belongings. When I went to Madras, I purposely went to see Cdr. Sonpar. He was surprised but showing no emotions asked me if I could carry a package for his sister who lived in London. I told him (I distinctly remember even now) “How do I know you are not giving me some contraband stuff so that I can be caught?” He was yelling at the top of his voice but I didn’t care and left.

It was from Fort St George that I went to Belfast in Northern Ireland on deputation to join the commissioning team headed by Cdr. Mahindroo, the commanding officer and was given the prestigious post of Chief of flight deck and served till I left the Navy in 1963.

The experience in the Fort, though short, was unforgettable for many reasons, but the feeling that I was living in a place from where the English started their rule in a small way but soon took over the entire sub-continent made me to go around and see it in detail. Those days the fort was totally dark at night as the lighting provided by incandescent light bulbs that were struggling for their existence was pathetic. Still, I used walk around and use the Wallajah gate to go into the city to have my dinner. It was scary when I returned as apart from the sentry at the gate there were no persons anywhere!

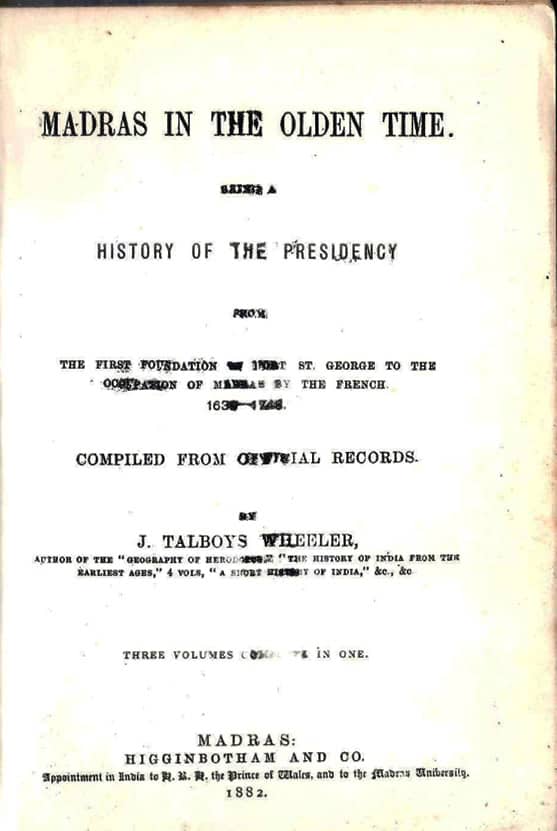

But these walks around the fort led me to study it. My maternal uncle ‘Chitti’ Sundararajan, then the chief newscaster at All India Radio had some books and I read with interest the way English lived in the fort and of Clive getting married in the church there. My uncle guided me to the Connemara Library where I could lay my hands on J. Talboys Wheeler’s Madras in the Olden Times and Col. Love’s three volumes on Madras.

Unfortunately, my study was cut short when I was asked to report to Bombay to proceed to Belfast leading a team of 30 sailors as part of commissioning crew of Vikrant. Since I was trained as a trainer, on my retirement in 1963, I was selected to be the head of National Institute of Port Management in Madras. But the then shipping minister Jagdish Tytler did not favour my appointment, due to a difference of opinion on a ship building contract earlier. However I was asked to be a visiting faculty in the Institute, by the Secretary, Ministry of Shipping and therefore relocated to Madras. Thus once again I got interested in Madras as a city and started researching on the same and I can say that I am indebted to Fort St. George for my interest in Madras history.