And so, finally, Victoria Public Hall is back to its old glory. And it has, in a sense, been returned to the public to whom it rightfully belongs. What, however, is of utmost importance is to appreciate this precious legacy and make sure that the place does not end up getting caught in a fresh maze of bureaucracy and worse, legalese. The accompanying article gives ideas and suggestions on what can be done. But before we go to that, we need to see what made VP Hall dysfunctional for over sixty years as a people’s venue.

The problems began probably when VP Hall was conceptualised itself. The land belonged to the Corporation, and the 3.14 acres was leased at a rent of fifty paise per ground (2400 sq feet) to the private Trust that ran VP Hall. Trouble seems to have begun as early as in 1921 when the Advocate General filed a scheme suit before the High Court. It sought to lay down the guidelines for the administration of the building and the subsequent decree became the basis for all future developments. Even in that suit, it was alleged that some of the trustees had tried appropriating the hall rent income. The Court stipulated that its permission would have to be sought if and when the Trust considered handing over the building to the Corporation.

In 1950, the Corporation sought control of the property and this was referred to Court. The Trust challenged the takeover and owing to this conflict, the Public Resort Licence of the Hall was cancelled in 1952 by the Corporation. Thus, the Hall could not rent out its premises for events and therefore received no income on that account till 1972! Of course, its lessees continued to be in occupation and paid their lease rentals but these amounts were so small that there was practically nothing for the upkeep of the premises. The litigation came to a conclusion in 1956 and the Corporation gained possession of the building and completed its renovation a year later. A fresh Trust Board was constituted comprising the Sheriff, the Mayor, members of various trade and commerce associations, a representative of the Maharajah of Vizianagaram and a nominee of the High Court. The Commissioner of the Corporation was the Secretary. Of course, with the suspension of the Corporation Council following the muster roll scandal, the office of Mayor fell vacant and the post of Sheriff was filled only sporadically.

The new Trust Board remained in charge of the Hall but, as the lessee, it began to sub-lease the premises to others. A line of shops came up on the eastern front and the Chennapuri Andhra Mahasabha, long a sub-lessee, built its own premises fronting the building. In addition, a hotel came up on the southern front. It must be realised here that while the main building did not have any activity or generate revenue for itself, practically everyone else did, including from film shoots. The building thus grew increasingly dilapidated.

The 99-year lease expired in 1985 and rather inexplicably, nothing was done till 2009, when the Board of Trustees decided to handover the premises to the Corporation. The sub-lessees went to Court on the grounds that the restoration of the building was not in any way impeded by their continued presence! This fortunately was overruled by the Court and was appealed against. This was dismissed. It was only then that the way was paved for VP Hall’s restoration, which due to the Metrorail work, was stalled again. Finally, we now have a restored VP Hall.

In the midst of all this, though it is not clear as to how the matter of ownership was resolved, there were attempts to restore VP Hall. The first of these, as per a plaque on the eastern entrance of the building, was in 1967 at the orders of the then CM, CN Annadurai. It is said that the then trustees of VP Hall were contemplating demolishing it and putting up a cinema theatre there! Anna prevented this and the restoration was duly ordered. It is not clear what was the outcome. It appears that the eastern portico was constructed as part of this, for it is architecturally completely out of synch with the rest of the building. Sadly, it has been retained.

We then move to 1992/1993 when industrialist Suresh Krishna became the Sherrif of Madras. He initiated moves for restoration and in 1996 when MK Stalin became the Mayor, the matter moved ahead. But it had to wait till 2010 when the Corporation allotted Rs 3.06 crores for the restoration. While the news reports of that time give a very comprehensive scheme of conservation, it is not clear as to what was done. The building certainly languished and went from bad to worse. A heritage walk in the premises, in 2010, revealed a stairway in a state of collapse, plenty of bats and a first floor that distinctly sagged. Then came Metrorail and the foundation of VP Hall was impacted though the superstructure fortunately remained stable.

Which brings us to the latest and happily, successful restoration. To quote The New Indian Express – “In May 2023, the Greater Chennai Corporation undertook a comprehensive conservation, revitalisation and seismic retrofitting project at a cost of Rs 32.6 crore under Singara Chennai 2.0. Though the work was given a 24-month deadline, it overshot by seven months.

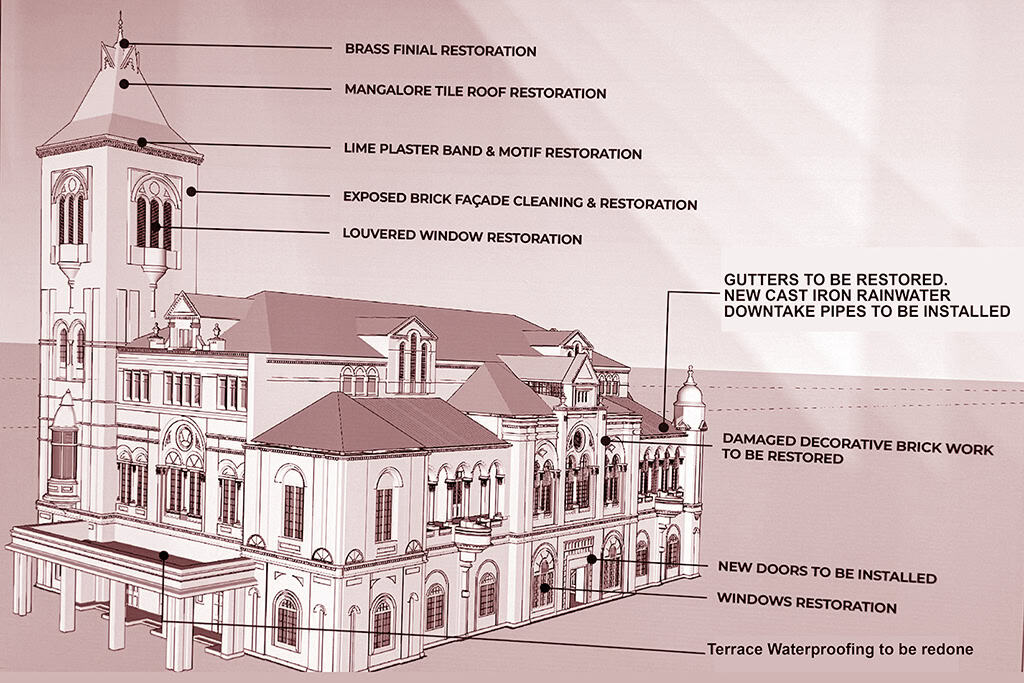

The official said the restoration was carried out to preserve the building’s original architectural character while enhancing its structural safety and functionality. The project included structural repairs, seismic strengthening, complete roof restoration, interior and exterior conservation works, upgrading of building services and architectural façade lighting. With a built-up area of around 2,200 sq m, the restored hall now meets modern safety standards while regaining its historic grandeur.”

The work, carried out by Abha Narain Lambah Associates of Mumbai, with actual restoration by Savani Heritage, certainly is most impressive. And it serves as an exemplar of what should be done with heritage buildings. The attention now shifts to how the Corporation will manage, and more importantly, make VP Hall a living heritage structure.

* * *

An Architectural Assessment

Designed in the Romanesque style and rectangular in plan, measuring approximately 46m by 26m, the new entry portico is at the eastern end. The ground and first floors contain two large halls capable of seating 600 people each, the latter fitted with a gallery at its eastern end. Special features include arcaded verandahs along the northern and southern sides supported on sleek Corinthian stone columns, and a tall square tower that rises at least three floors above the rest, covered by a curved pyramidal roof typically of many other buildings of this period. An intricately carved terracotta frieze resembling Islamic calligraphy adorns the top of the tower.

Built of red brick and pointed with lime mortar, the intermediate floor is of Madras Terrace while the roof is a large hip with Mangalore tiles and dormers at the ends and along its length. As in other buildings of a similar style and form, the Town Hall too appears more human in scale than that expected from a building of its size, mostly due to its massy brickwork, sleek and slender details and large tiled roof. The walls of the top floor are highly embellished with decorative and painted plaster work on the interior and the gallery constructed completely of wood.

Reproduced from Madras The Architectural Heritage by K Kalpana and Frank Schiffer.