Abstract

This article sheds light on a medical bimonthly, the Madras Journal of Medical Science (MJMS), which was active between 1850 and 1854. A unique aspect of MJMS was that it was published by the apothecaries and dressers of the Madras Subordinate Medical Service for their professional development. Similar to any professional journal of the mid-19th century, this journal included a few original case reports (referred to as literary contributions) by the apothecaries and dressers working with the Madras Medical Establishment (MME). This journal also included a few paraphrased articles from contemporary British medical journals, as well as featuring some locally relevant information related to the medical profession. This effort, aimed at academic growth, made by the subordinate medical staff of MME and not by the mainstream, higher-qualified medical personnel, impresses as valiant and daring.

Introduction

Romeo

‘… … … Let me have

A dram of poison, such soon-speeding gear

As will disperse itself through all the veins

That the life-weary taker may fall dead, …’

Apothecary

‘Such mortal drugs I have, but Mantua’s law

Is death to any he that utters them’.

William Shakespeare

Romeo and Juliet (Act 5, Scene 1, lines: 58–67)

Nearly 50 professional medical journals, published in English, were issued in India in the 19th century. Some of them lasted 3–5 years, whereas a few others lasted up to 20 years. One premier journal was the Indian Medical Gazette, administered by officers of the Indian Medical Service in Calcutta (now Kolkata), which appeared from 1866 and survived until recent times.1 The Madras Presidency also contributed to professional medical journalism, with notable publications such as the Madras Quarterly Medical Journal, in addition to the Madras Quarterly Journal of Medical Science, the Monthly Journal of Medical Science, the Transactions of the South Indian Branch of the British Medical Association, and the Madras Medical Records, all of which appeared between 1840 and 1910. In the article entitled ‘Medical journalism in the 19th century Madras’,2 we mentioned Madras Journal of Medical Science (hereafter MJMS) but with no details. Recently, we managed to obtain some details about MJMS, and this article is a consequence of that. Notably, MJMS was initiated and administered by medical personnel from the subordinate medical service (SMS) – specifically, the apothecaries and dressers – of the Madras Presidency, rather than by the British-trained, qualified medical officers appointed as executive, mainstream medical personnel at that time.

The SMS: Apothecaries and Dressers

The SMS of the Madras presidency was established in 1812, the earliest of its kind in India. The SMS included non-commissioned medical servants of either European or Eurasian descent (Anglo-Indians), who were designated variously as ‘apothecary’, ‘second apothecary’, ‘assistant apothecary’, and ‘medical apprentice’, depending on their level of seniority. Those of Indian descent, who completed the same training and passed relevant examinations, were referred to as either ‘first dresser’, ‘second dresser’, ‘medical pupil’.3

The Medical School in Madras (presently Chennai) (the Madras Medical School [MMS]) was established in the 1st week of February 1835, whereas the Bengal Medical School in Calcutta (Kolkata) was established a week earlier. Until 1850, medical training offered at the MMS culminated with the award of the title ‘apothecary’ or ‘dresser’. With the commencement of the graduate programme, leading to the award of the title ‘Graduate of Madras Medical College’ (GMMC) in 1847,4 the MMS was rebranded as the Madras Medical College in 1850. The training and examination processes for apothecary and dresser candidates of European, Eurasian and Indian descent were the same. However, the Europeans and Eurasians, when qualified, were eligible to use the title ‘apothecary’, whereas Indians, particularly those employed with the Madras Army, were to use the title ‘dresser’. Before 1835, i.e. before the start of MMS, voluntary trainees working in army hospitals after a certain number of years, possibly two, were granted the titles ‘apothecary’ or ‘dresser’.

One reason for establishing MMS in 1835 was to train medical personnel for formal recruitment into military service. The term ‘dresser’ was used only in the Madras Presidency, whereas in the Bengal Presidency, ‘stewards’ and ‘assistant stewards’ were used further to ‘apothecaries’. Madras followed the procedure of subjecting assistant apothecaries and assistant dressers to an examination before promoting them to full apothecaries and full dressers. This practice influenced the Bengalis to follow suit.5

In Madras, candidates seeking training as apothecaries and dressers were subject to an examination for selection as apprentices. The Madras Medical Board considered the qualified for formal study towards the titles of apothecaries and dressers in MMS, which included lessons in anatomy, materia medica, pharmaceutical chemistry, dissections and clinical instruction in medicine and surgery. At the end of 2 years, they sat for an end-of-programme examination. The successful were drafted either into military service or into the Madras General Hospital. Promotion of an ‘Assistant Apothecary’ to ‘Apothecary’ (similarly, ‘Assistant Dresser’ to ‘Dresser’) was through examination as well. The apothecaries in the Madras public hospital service held the rank of Warrant Officers, which empowered them to issue arrest warrants to soldiers up to the rank of a sergeant.6 They were allowed to practice medicine privately.7 Details of the dress code for the apothecaries (warrant officers) are available in Cornish.8 Robert Clerk, Secretary to Government of Fort St. George, has produced a report entitled the Code of Regulations for the Medical Department of the Presidency of Fort St. George,3 which speaks of the roles and responsibilities of executive medical officers (pp. 51–96), subordinate medical servants (pp. 97–102) and superintending and staff surgeons (pp. 103–122) at length.

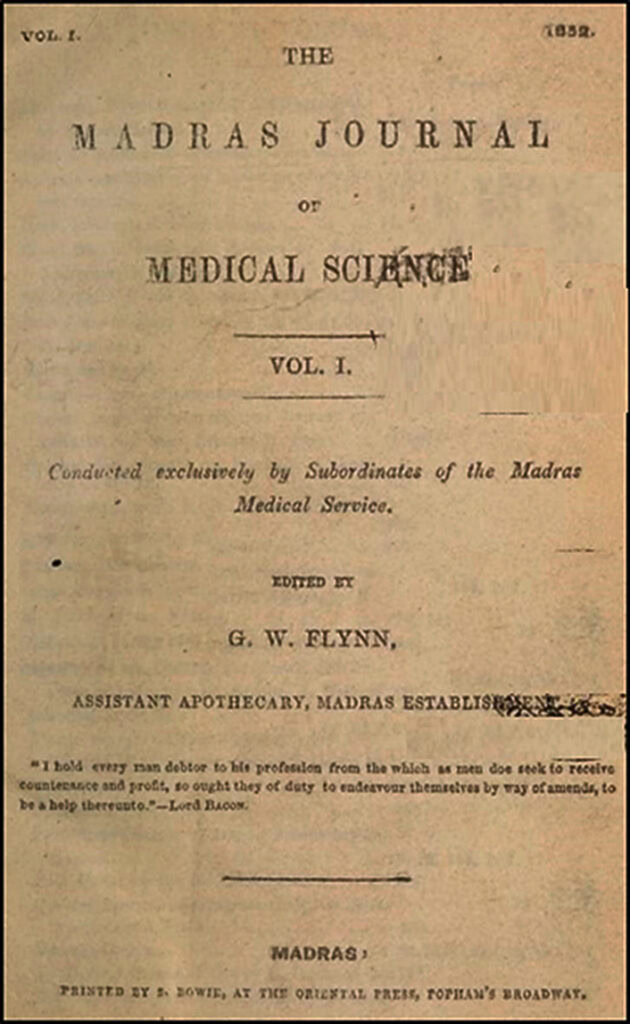

The MJMS, October 1852

The first issue of MJMS, printed in Oriental Press (OP), Madras, appeared in October 1852. OP, then located in Popham’s Broadway, Madras-business district, was managed by one Samuel Bowie. OP appears to have been a popular printery since many government reports and private tabloids were printed here, e.g. Instructions which have been Issued from Chief Engineer’s Office from Time to Time, for the Guidance of Engineers, Madras Railway (1858), a religious monthly, the Latter-Day Saints’ Millennial Star and Monthly Visitor promoting Mormonism edited and published by one Richard Ballantyne, an American Mormon, living in Madras.

GW Flynn, an Assistant Apothecary attached to the Madras Medical Establishment (MME), has signed as the editor on the first issue of MJMS. GW Flynn or George William Flynn (GWF) (source: https://www.wikitree.com/wiki/Flynn-1852, accessed 02 March 2025) was born to George Flynn and Charlotte (an Indian native) in St. Thomas Mount, Madras, in 1824. George Flynn (Senior) was a trained apothecary from Cork, Ireland, who arrived in Madras in the early 19th century and worked with the East India Company in Madras, most likely as an apothecary. It is possible that GWF was trained in the newly established MMS for his apothecaryship.

Fig 1. Cover page of the inaugural issue of Madras Journal of Medical Science, 1852.

The prospectus in the first issue of MJMS indicates that this journal would appear every other month, i.e. six issues per year (Fig. 1), and each issue was priced at Rs. 1. All technical papers (referred to as ‘literary contributions’) were to be received by the GWF, c/- The Medical College, postpaid. Other communications were to be sent to JH Stanthorpe, Vepery, who was likely the owner of OP. A statement (p. 4), reproduced below, in this prospectus offers an interesting read:

‘This Journal, which will be called the Journal of Medical Science will be conducted entirely by the Medical Subordinate Department of the Presidency (i.e. Madras Presidency) and will be supported by literary contributions from the same source’.

GWF further says that the chief objective of this journal (p. 1):

‘… is to afford intelligent and studious Medical Subordinates of this (= Madras) Presidency, an opportunity of exhibiting proofs of their reading, experience, and observation, in the great Field of Disease; of proving that the talents confided to their care have not been allowed to lie dormant and unimproved; and of showing their superiors of every class that they have, as a body, resolved to secure approbation by their zeal, intelligence and perseverance. This Journal is intended to be the representative of the Medical Subordinate Department, an exponent of its abilities, knowledge, and progress, and not be it remembered, a harbour for its private feelings, or its petty jealousies’.

Multiple remarks in this prospectus evoke curiosity regarding the style of presentation and the words used, but they are remarkable in their content and message. A few samples are reproduced here (pp. 5–6) with supplementary explanations in italics and brackets for archaic terms and potentially confusing possessive pronouns:

‘It is necessary that the Projector (= publisher) and Editors of this Journal should clearly intimate the ground they intend to occupy in conducting it. In order to avoid misapprehension, as much as possible’.

‘The Editors regard their duty in this light as sacred; they will spare no pains to maintain the honourable and useful character of the Journal; but they will not allow it to be the medium of any unamiable altercations, or the means of propagating those personal and private janglings (= discordant notes) which, when admitted into any Journal, alike derogate from its respectability and its usefulness’.

‘With these principles, which they (= editors) intend to dwell upon more fully in their opening number, the Editors of this periodical beg humbly to present their bantling (= this new journal) to the patronage of Medical Public. From the liberality and kindness of Medical Officers, they (= editors) confidently expect both countenance (= approval) and support, for they have already received from many, proofs of their warm interest in this new and hitherto untried undertaking’.

‘From their subordinate brethren, they (= the managers of MJMS) expect not only pecuniary, but also literary, subscriptions – one alone will not do; without money they must make their final bow, and without literary contributions their little Journal must fall to the ground’.

‘Original communications will occupy a prominent part of the Journal; these will be carefully and in every case impartially selected, and will, the editors trust, be found to be of a kind reflecting hono(u)r upon their authors, and credit upon the subordinate department generally’.

The first Issue: Contents

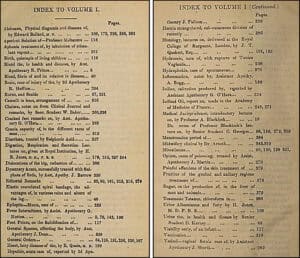

Fig 2. Contents pages (indicated as index) from the inaugural issue of Madras Journal of Medical Science.

MJMS was created to promote the intellectual growth of apothecaries in Madras. The SMS promoted their scientific reports (Fig. 2). Eleven articles — 7 review articles — by the Madras apothecaries feature in this issue: The blood in health and disease (R. Prince), Cracked feet (G. O’Hara), Intermittent fever (G. Norton), General spasm (J. Dean), Inflammation (A. Bogg), Opium poisoning (J. Martin) and Salivation produced by iodine (G. O’Hara) and four case reports – acute dysentery treated with the sulphate of soda (J. Barrow), a case of the injury of the brain (R. Huffton), an acute case of hepatitis (J. Falloon), a case of vaginal fistula (J. Shortt). This issue also features a selection of articles written by senior medical professionals, primarily professors of medicine in the UK and occasionally from the Madras Medical College. For example, Ambrose Blacklock (1816–73) was a professor of medicine and surgery at Madras Medical College in the 1850s, whose class lectures on medical jurisprudence have been reproduced in this issue. Additionally, 21 short articles (one page or less) on various medical themes, such as burns and scalds, dislocation of the hip, strangulated hernia, epilepsy, and hydrophobia, written by anonymous authors, also feature. Furthermore, this issue also features brief articles by trainee students of the apothecary study programme, such as W. Baker’s on cholera and D. Karney’s on albuminous and fatty urine.

Comment

Only four volumes of MJMS were issued (1850–1854). All of them are freely available on the Wellcome Collection, London, for anyone interested (https://archive.org/details/b31516816, accessed 29 November 2024).

This effort, led by GWF, a member of the practicing apothecaries of Madras in the 1850s, is laudable. One possible reason for the launch of this journal by the members of the SMS of Madras was to demonstrate their academic and intellectual capabilities, as well as their personal academic growth.

Apothecaries and dressers in Madras have published case reports in professional medical journals, such as the Madras Quarterly Journal of Medical Science edited by Howard Montgomery and William Cornish, who were executive medical officers of the MME. However, the frequency of publications by the apothecaries and dressers was far and few between compared with those by better-qualified executive surgeons. For example, George Davis, an assistant apothecary attached to the primary department of MMS has published a paper entitled a ‘Case of chylous urine’.9 A few other papers, mostly referring to single-case studies by Madras apothecaries, are available in various medical journals published from Madras.2

The Madras apothecaries launched the Madras Apothecaries Society (MAS) on 30 May 1864,10 styled after the Worshipful Society of Apothecaries of London. The MAS aimed to promote and advance medical science and knowledge. For example, at their first business meeting on 28 July 1864, a seminar on ‘Cholera, its aetiology – prophylactic and therapeutic management’ was presented by an unnamed member of the MAS. The cholera aetiology seminar was followed by brief presentations on ‘dog bite and hydrophobia’ and ‘relationship between nerve force and electricity in cholera management’ by two other MAS members. The MAS sustained till 1871.11

Among the several names of apothecaries who have published articles in the inaugural issue of MJMS, we could recognize the name John Shortt (b. 26 February 1822), who started as an apothecary from MMS in January 1846. He went to Scotland and earned a Doctor of Medicine degree and subsequently became a Member of the Royal College of Surgeons in London. He also qualified as a Member of the Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons. He returned to Madras and joined MME as an Assistant Surgeon in July 1854. He was admitted into the Membership of the Royal College of Physicians of London in 1859 and was elevated as a Full Surgeon on 20 September 1866. Shortt was the Superintendent of Vaccination in Madras. He was a prolific writer and was recognized with admission as a fellow of the Linnean Society of London and the Zoological Society of London. He was the corresponding fellow of the Société d’Anthropologie, Paris and the Berliner Gesellschaft für Anthropologie, Ethnologie und Urgeschichte. As an elected member of the Obstetrical Society of London, he was the Secretary of the Madras Chapter of the Obstetrical Society of London. He retired as Deputy Surgeon-General of Madras, holding the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel, when Edward Green Balfour was the Surgeon-General. Unverifiable notes on Shortt indicate that he held a Licentiate in Dental Science. Post retirement, Shortt lived and died in Yercaud. His memorial stone is located at the CSI Anglican Church Cemetery, Yercaud.12

At present, the terms ‘Apotheker’, ‘Apothekerin’ (German) and ‘apothecaire’ (French) imply a pharmacist, whereas in English-speaking nations, the term ‘pharmacist’ is used. However, until the end of the 19th century, in India, an apothecary not only referred to a person who performed the duties of a pharmacist but also functioned as a junior medical officer, treating the sick, and filled the space between executive-medical officers and nurses. In 1894, the designation of apothecaries (and dressers) was abolished in the MME and replaced with ‘assistant surgeons’.

With the start of World War I in 1914, the Madras government required trained medical personnel for posting in war zones. Hence, it established medical schools all over the presidency, e.g. the Royapuram Medical School (presently, the Stanley Medical College and Hospital, Chennai), Thanjavur Medical School, and Madurai Medical School. These medical schools offered short-term medical training to high school leavers, and after three years of training in medicine, surgery, and midwifery, the graduates were recognised as Licensed Medical Practitioners (LMPs). The LMP programme continued for a few years and many Indians qualified for that title and joined the army as medical officers. When women were admitted to Madras Medical College in the 1880s, they were admitted into the Licentiate in Medicine and Surgery (LMS), a programme that involved a shorter time and lesser rigour than the GMMC title (equivalent to the later offered M.B.C.M. programme) then extant at Madras Medical College. It is highly likely that the apothecary-dresser academic training of earlier times was rehashed in the starting and conducting of the LMP and LMS programmes in Madras in later days, although no concrete evidence exists.

What is admirable in the context of the short-lived MJMS is that the Madras-trained subordinate medical servants launched this Journal. The following text by the editor (p. 34) impresses:

‘Prior to the institution of the Medical School at this Presidency had such a project as the one now under consideration been started, failure must have been the inevitable result owing to the want of individuals possessing the requisite education to enable them to contribute anything of sufficient interest for publication; but matters are now changed for the better; – the great proportion of our department consists of men who have received to a greater or less extent, a professional education, the remainder being subordinate of tested qualifications, acquired by their own industry and perseverance – creditable examples of what can be effected by unaided application and long continued observation of disease. We expect much assistance in this our new undertaking particularly from our junior members, and we hope sincerely we shall not be disappointed in our expectation of contributions both numerous and good’.

— by Ramya Raman and Dr. A. Raman

References

1 Indian Medical Gazette, past, present, and future. Indian Med Gaz 1897;32:381–3.

2 Raman A. Medical journalism in 19th Century Madras. Curr Sci 2010;99:123–6.

3 Clerk R. Code of Regulations for the Medical Department of the Presidency of Fort St. George, Government of Fort St. George (Government of Madras). Madras: Asylum Press; 1833. p. 228.

4 Raman A. G.M.M.C. Diploma of the Madras Medical College. Indian J Hist Sci 2020, 55:1847–63.

5 Colville JW, Elliott HM, Beadon G, Grant J, Forsyth J, Dutt R, et al. Report on Medical Colleges in Bengal. In: Colville JW (ed). The General Report on Public Instruction in the Lower Provinces of the Bengal Presidency for 1847–1848. Calcutta: W. Ridsdale, The Military Orphan Press; 1848. p. 71–118.

6 The authority of medical subordinates. Madras Quarter J Med Sci 1863; 7:255.

7 Rights of medical men in government employment to engage in private practice. Madras Quarter J Med Sci 1863;7:256.

8 Cornish WR. A Code of Medical and Sanitary Regulations for the Guidance of Medical Oficers Serving in the Madras Presidency II. Madras: Government Press; 1870. p. 269.

9 Davis G. Case of Chylous Urine. Madras Quarter J Med Sci 1860;1:180–4.

10 Madras Apothecaries Society. Madras Quarter J Med Sci 1865; 8:466–73.

11 Sen BK. Growth of Scientific Periodicals in India (1788–1900). Indian J Hist Sci 2002;37:S47–S111.

12 Raman R, Narayanasamy C, Raman A. Surgeon John Shortt on native cattle breeds of Southern India in 1889. Asian Agri Hist 2016;20:93–105.